I’ve spent a good amount of time at book stores in the English speaking world. At times, it feels excessive, to the point where I question if the time perusing the books would have been better spent reading them. Reading is the point of books, I believe (this may sound obvious, but it's not and worth mentioning). And yet, books have a meaning of their own outside of the words inside them. They are the covers, the typography, the images, the material...in short, what truly defines a book is the materiality, the design and content combined. Literature may be best visualized now by an e-book...the words reign supreme while it has an almost negligible materiality. The differences of the ‘digital book’ may help us think about the book.

While at the University of Wisconsin, I had the pleasure of working in the Special Collections and Rare Books Department. I was able to see, firsthand, some of the finer specimens of the book. Publications from the Kelmscott Press, Audubon's Elephant Folio, Newton’s manuscripts, alchemy manuscripts, etc... A first edition, first printing can sometimes bring people to spend thousands of dollars for a piece of publishing history. An inscribed copy, especially from a reclusive author, can add additional value to the book...but these things don’t necessarily add additional value to the literature - the substance inside. What about the other elements, though? The paper selection? The weight or smell of the book? The size of the margins? Taken separately, their impact is unnoticed by most people and yet, together, the elements that make these books objects have a major effect on the reader.

Upon my arrival in Taiwan four years ago, the differentiation was real. There was truly only the physical book since the content (I will say the literature) was all in Chinese. This made the written content as good as non-existent for me. What I saw was the book craft, and the surface imagery of these characters. I bought nothing and I looked rarely. Certainly there were intriguing books and covers, but with the substance lacking, so too did my interest in much perusing or consuming.

Fast forward to three years later when my Chinese attained a level of understanding that allowed me to grasp the meaning of the title and sometimes even read a large portion of the contents inside. With this change, these beautiful objects transformed into the more substantial book. There is an extreme beauty and effect in the philosophy of the e-book - the writer's words stand on their own in a nearly level playing field. And yet, the materiality of the book and the things that lay outside of literature tend to enrich our experience in a way these new devices do not. Reading is not just about our sense of sight just as listening is not just about our sense of hearing. The other senses, defined or not, are always influencing us. The book - its typography, images, paper, size, literature - is a wonderful sum of its parts.

I wanted this little brief introduction to work as an introduction to these few books I’m sharing with you as well as how my experience with Chinese books helped me think differently about the book. The books that follow are of many different sorts - some I chose for the superficial and direct reason that I found them arresting and attractive. Some I bought for their literary content. As I packed up to move, these few books were among my most valued, so I share them with you. Don't pay too much attention to the section heads - there's lots of overlap and its just my way of making this random selection a little more digestible.

Enjoy.

Relatable and Translatable

The dramatic differences between Chinese and English present an extreme challenge to translators, especially with written translation. Roughly speaking, Chinese characters represent words or ideas and have little in common with the strictly phonetic latin alphabet (although many chinese characters do actually have phonetic elements but the rules vary greatly, to the point where many modern Chinese readers rarely think about them).

So how do you translate an English title into Chinese? Chinese takes a few different routes, the two most common are:

1.) Use the sounds of a character to mimic the sounds of the english word (Sometimes, the characters have a clever meaning along with their similar sound...sometimes there is no meaning at all, as below)

e.g. 湯姆索亞 TangMu SuoYa is Tom Sawyer (This has no usable meaning - if forced to translate, it would be something like ‘soup female tutor search asia’)

2.) Use characters with a similar meaning to represent the title (with no attempt for phonetic similarity

e.g. 聖經 Sheng Jing (‘holy scripture’) is The Bible

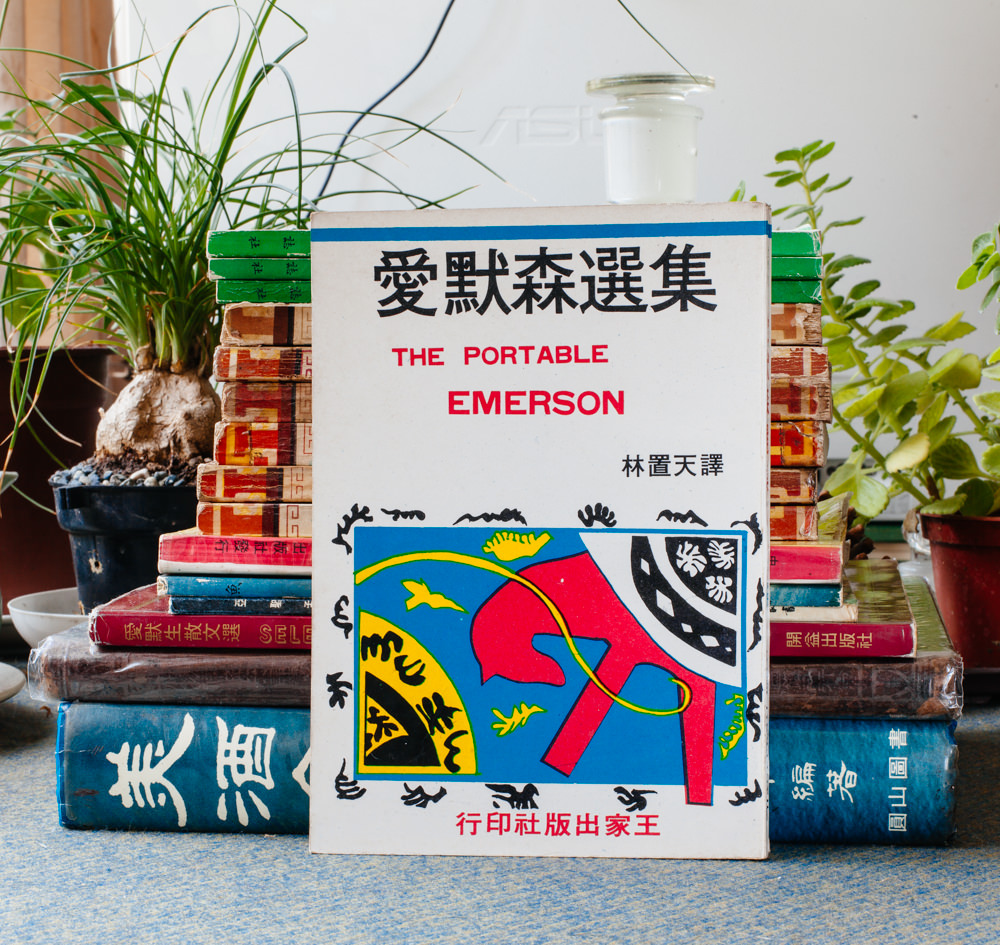

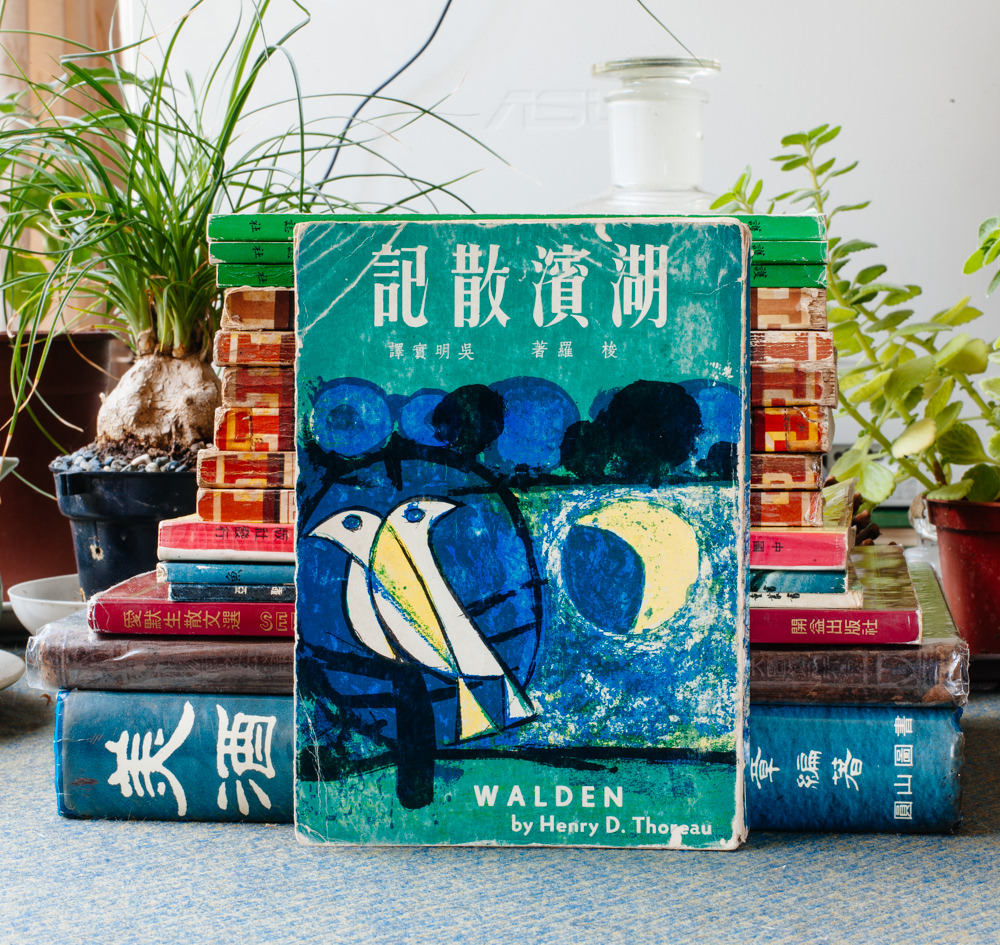

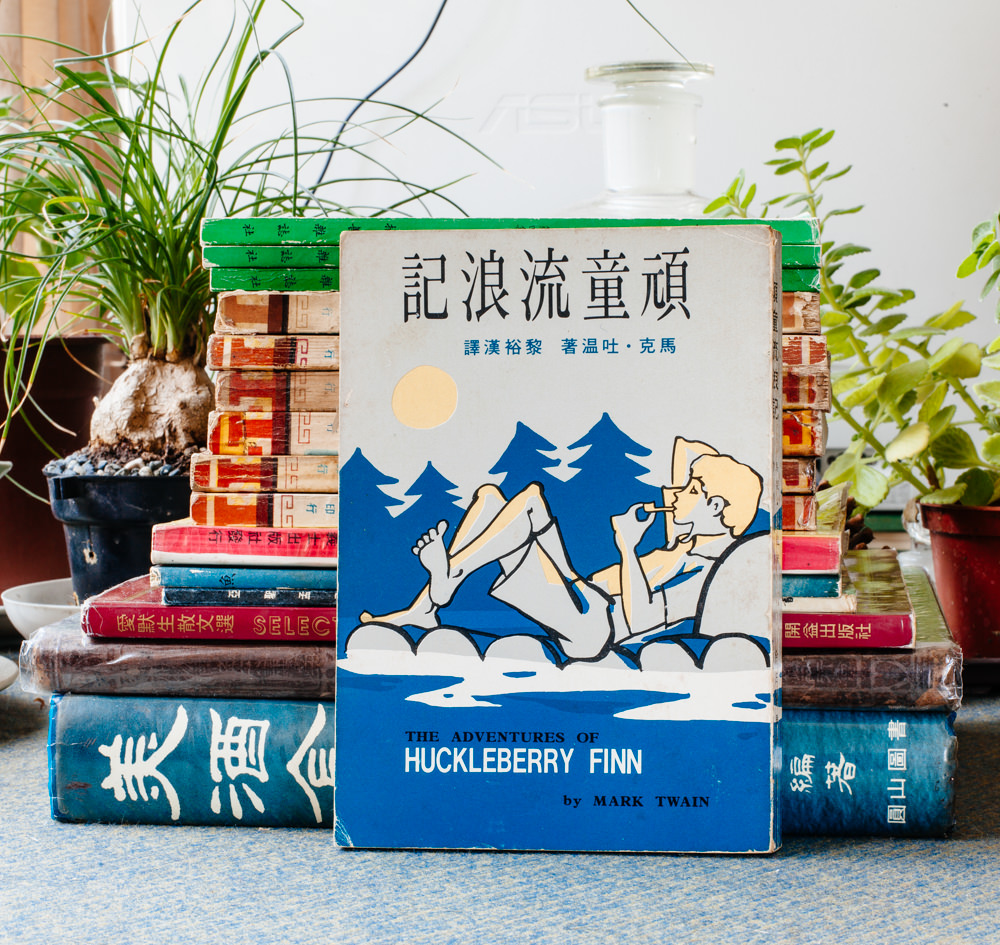

With that little intro, here are the titles for the first set of books pictured above:

The Portable Emerson: The translator's transliteration of Emerson's name is informed and phonetically similar: '愛默森' (the pronunciation is 'ai' 'mo' 'sen' - say those fast and you will understand why). The characters mean 'love,' 'silent', and 'forest.'

Walden by Henry David Thoreau: Walden is translated as Essays from the Lakeside with no phonetic similarities. And Thoreau? 亨利·大衛·梭羅 (Hēnglì·dà wèi·suō luó) - a purely phonetic representation.

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain translated as The Wayward Wanderings of a Mischevious Child

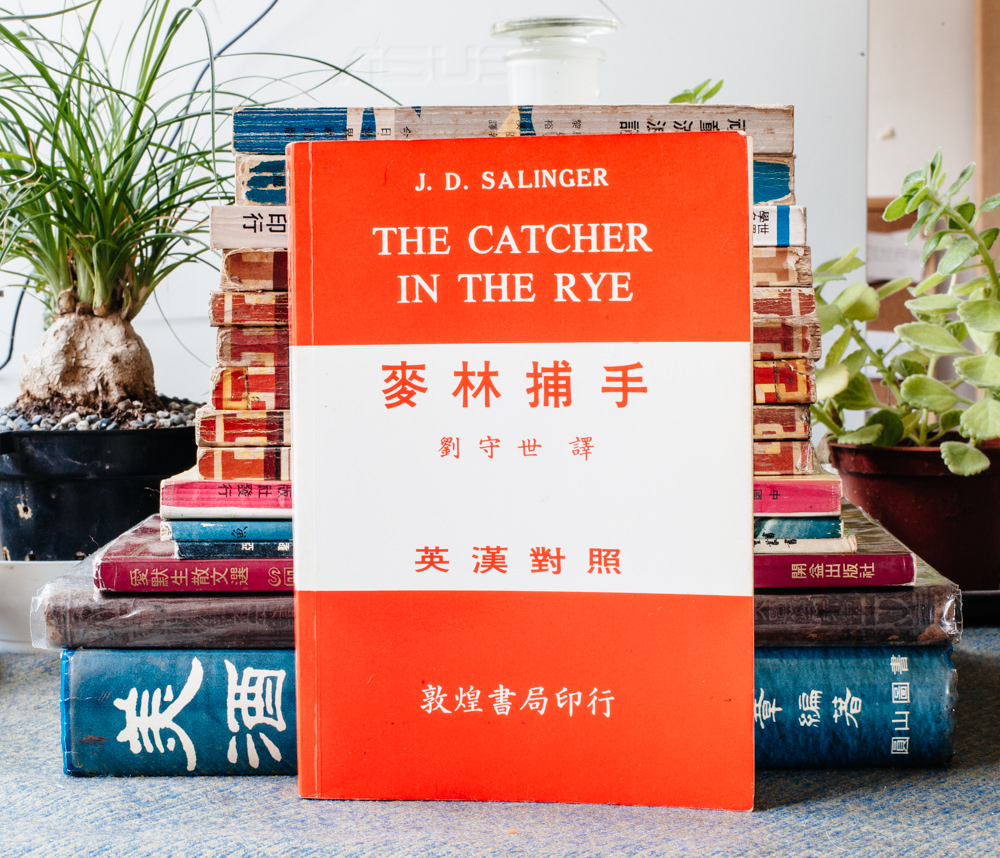

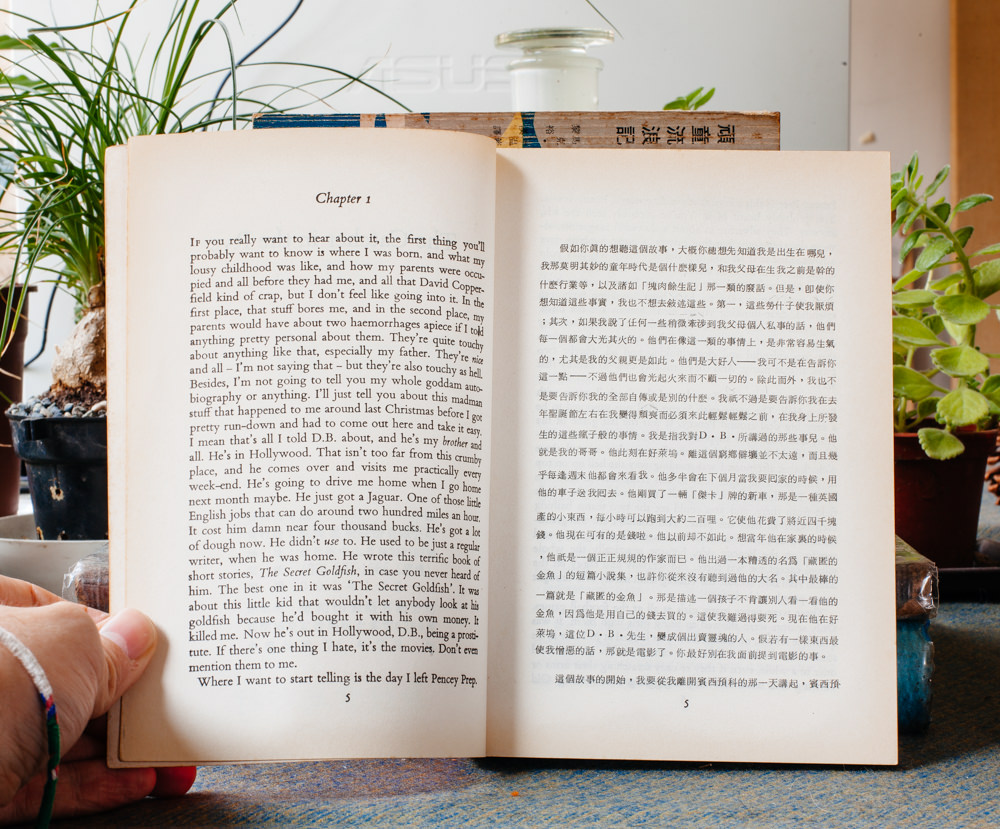

The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger is Catcher in the Wheat Field (here's a newer and less subtle variation on the cover that I saw at the bookstore)

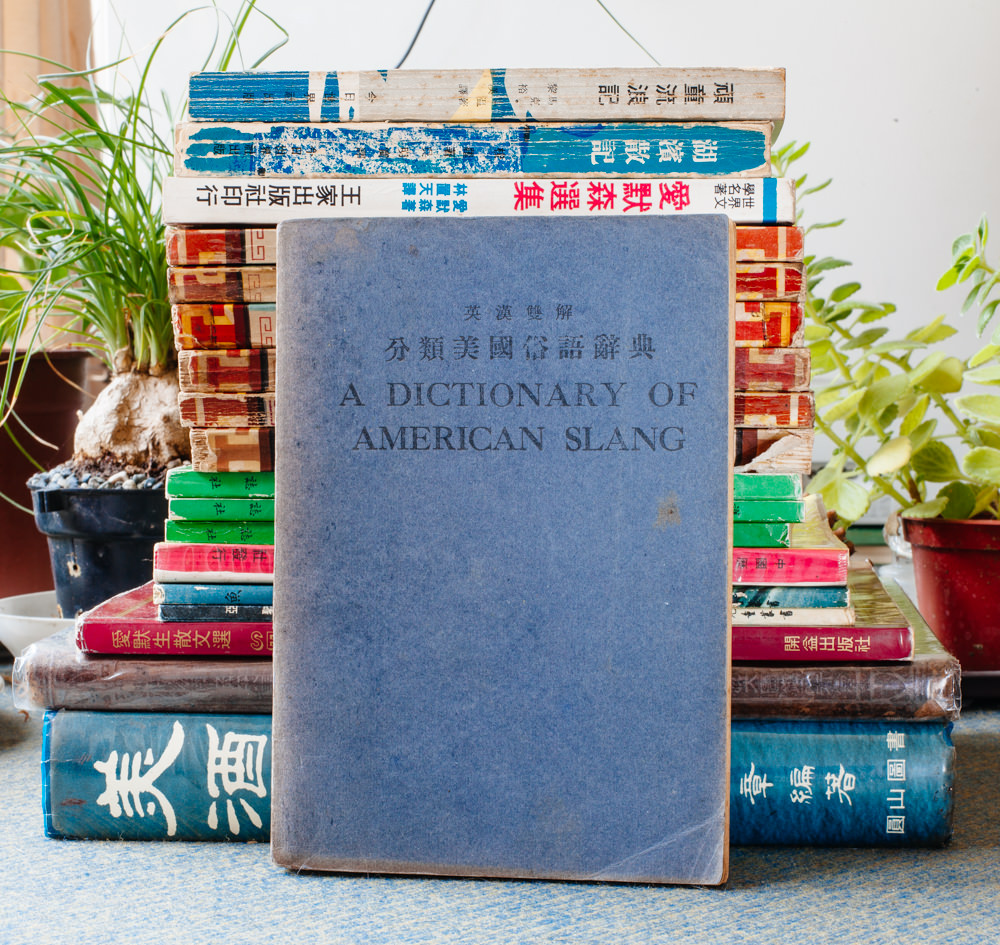

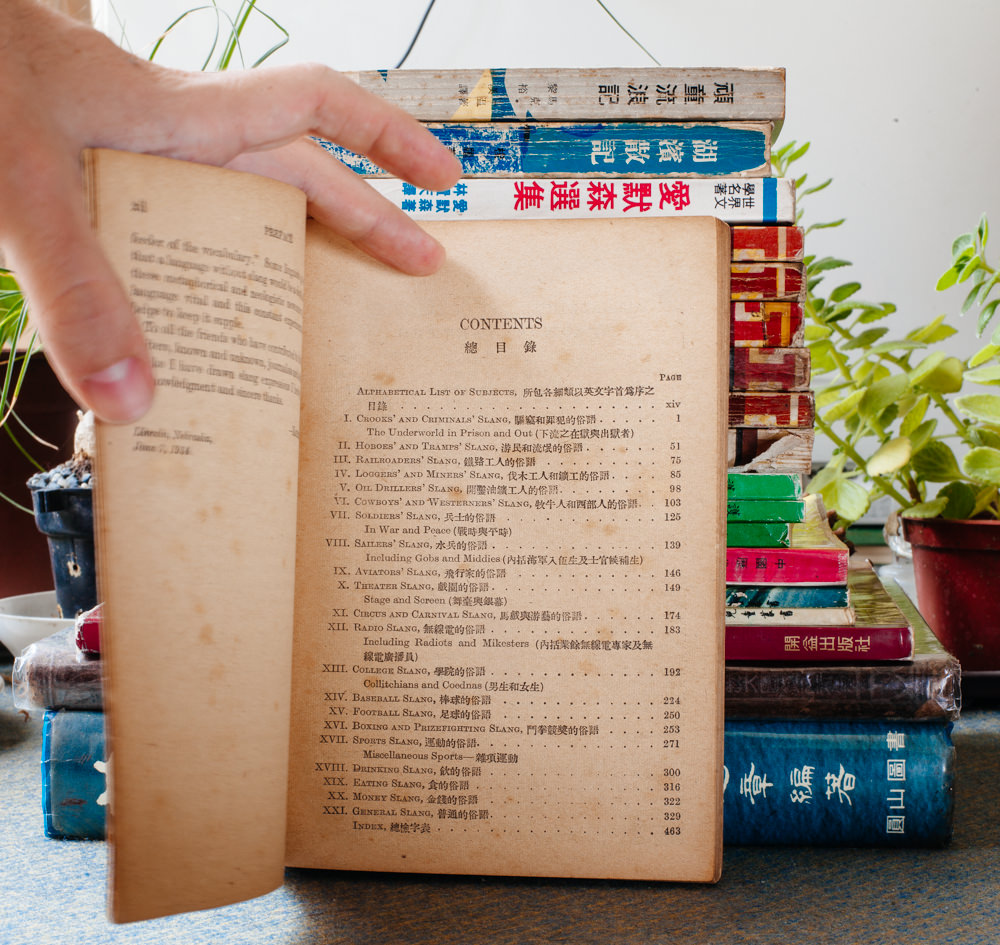

A Dictionary of American Slang by various authors

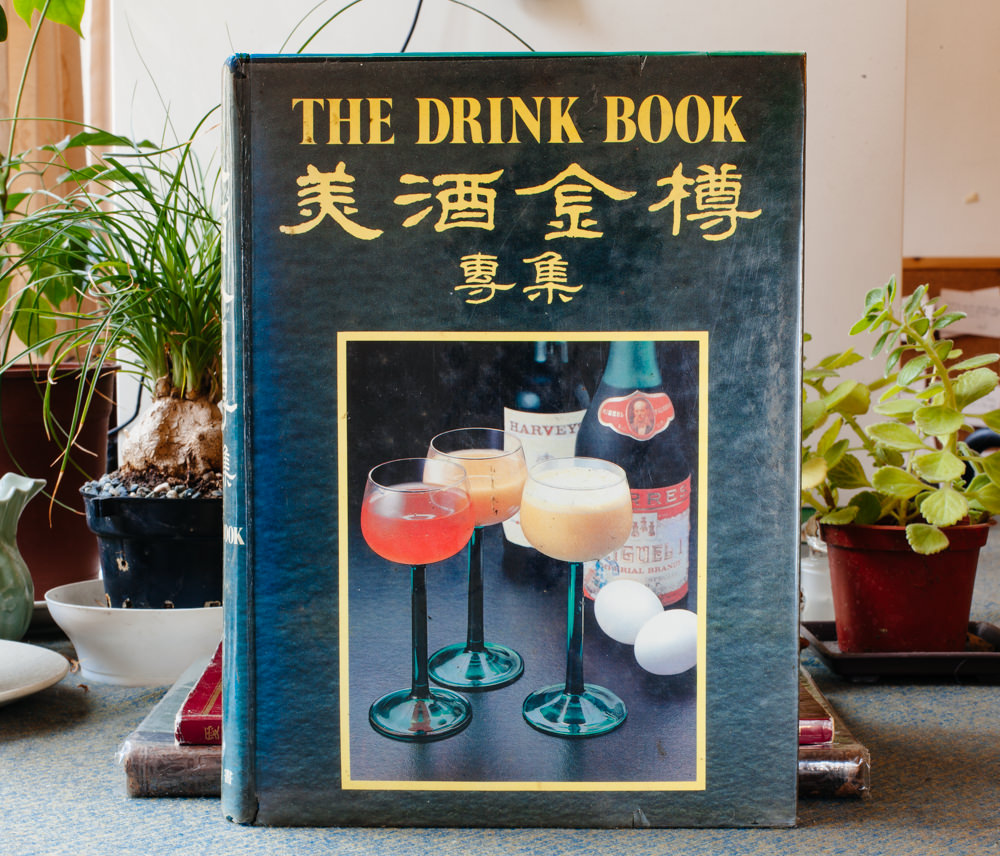

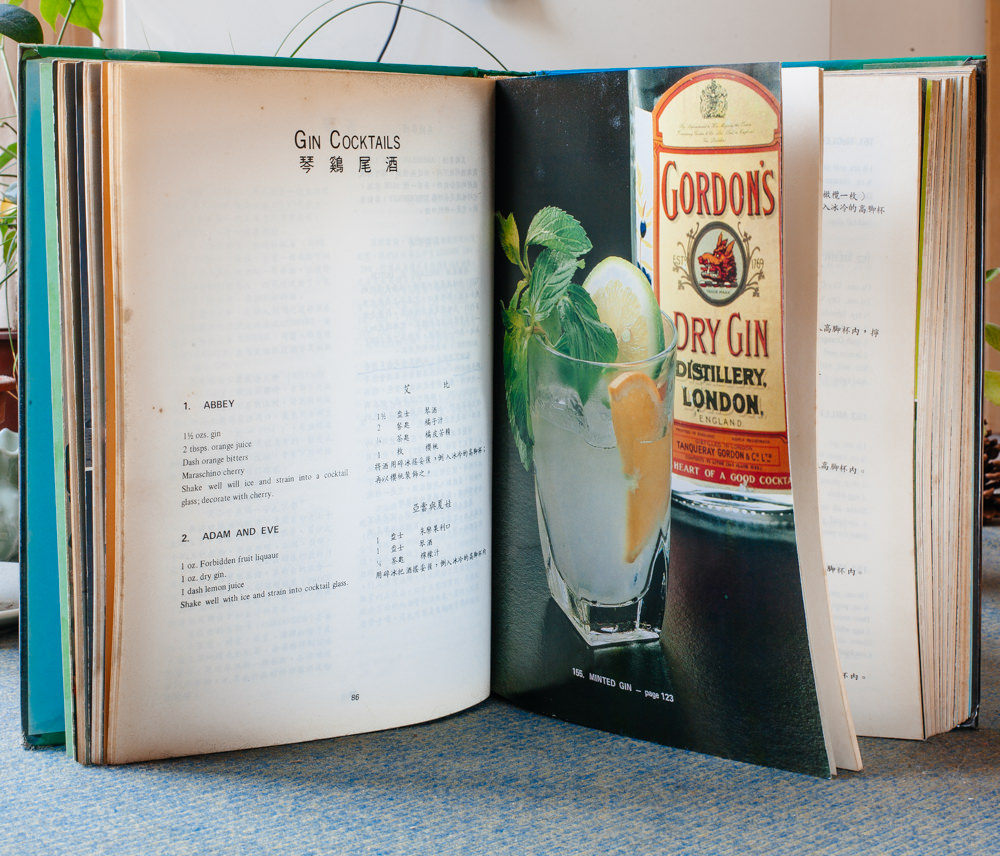

The Drink Book by various authors

Beauty

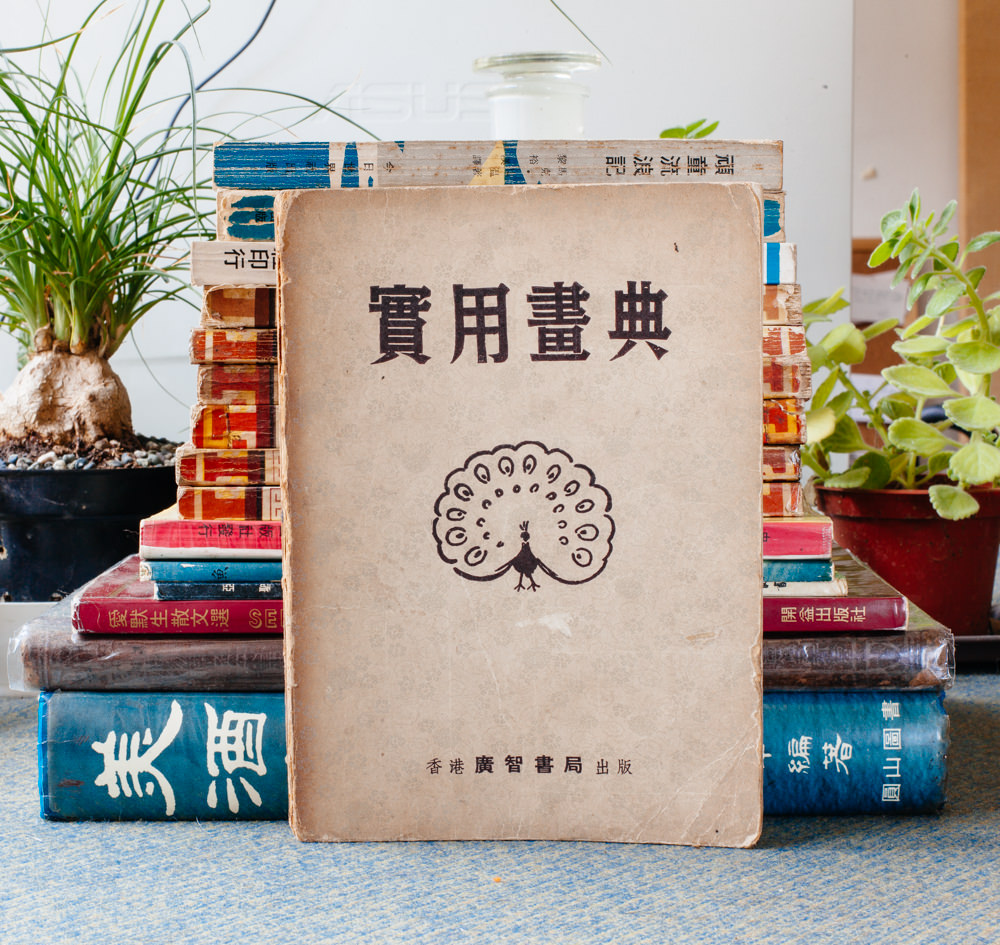

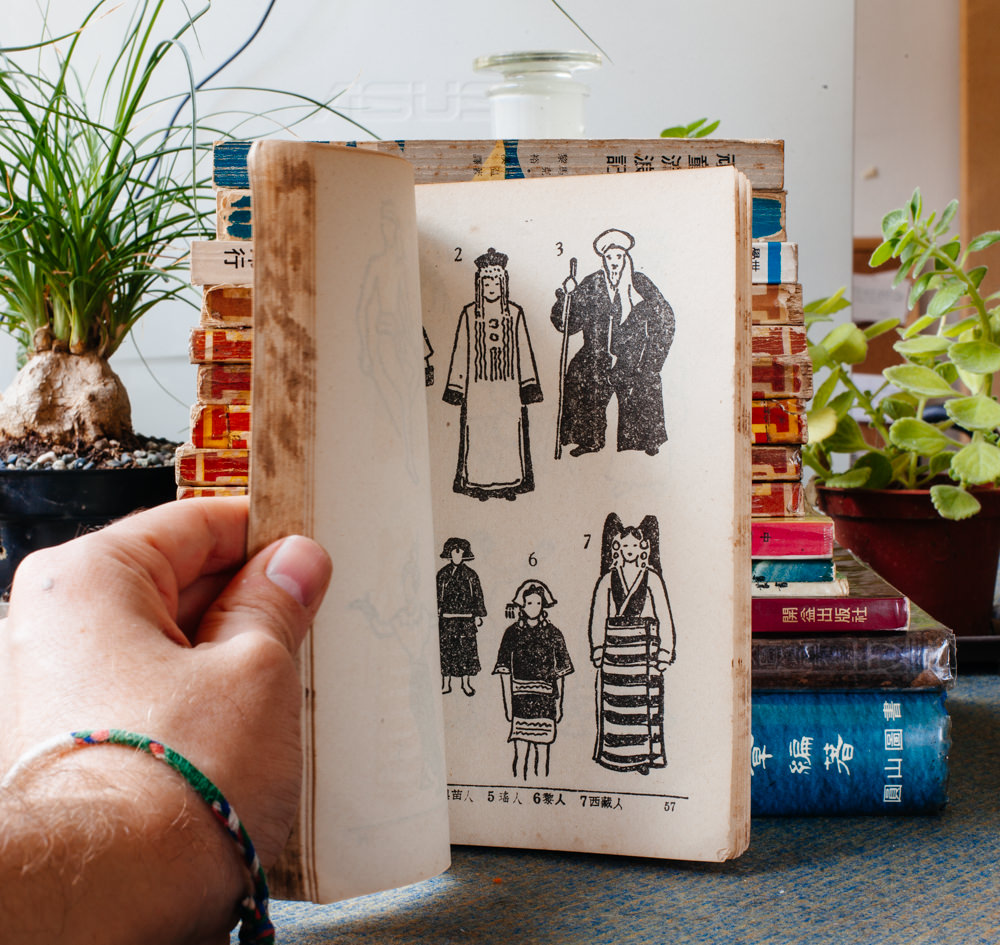

Practical Picture Dictionary

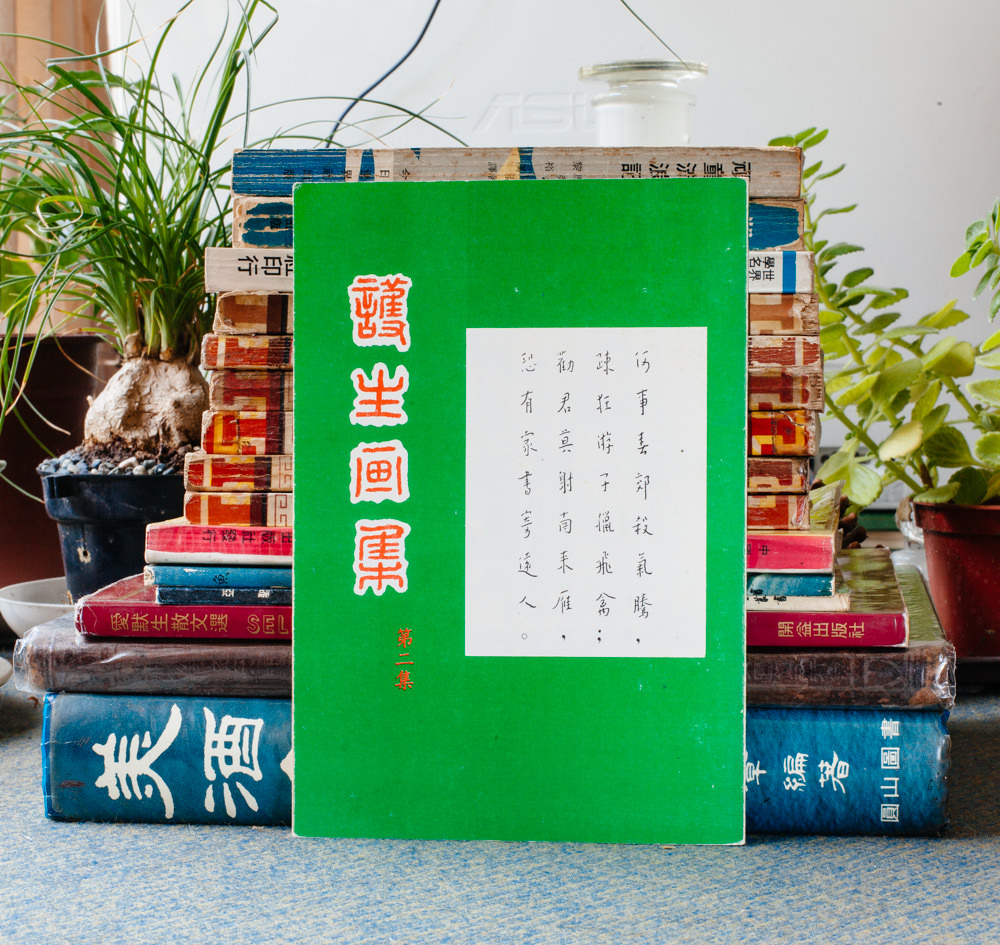

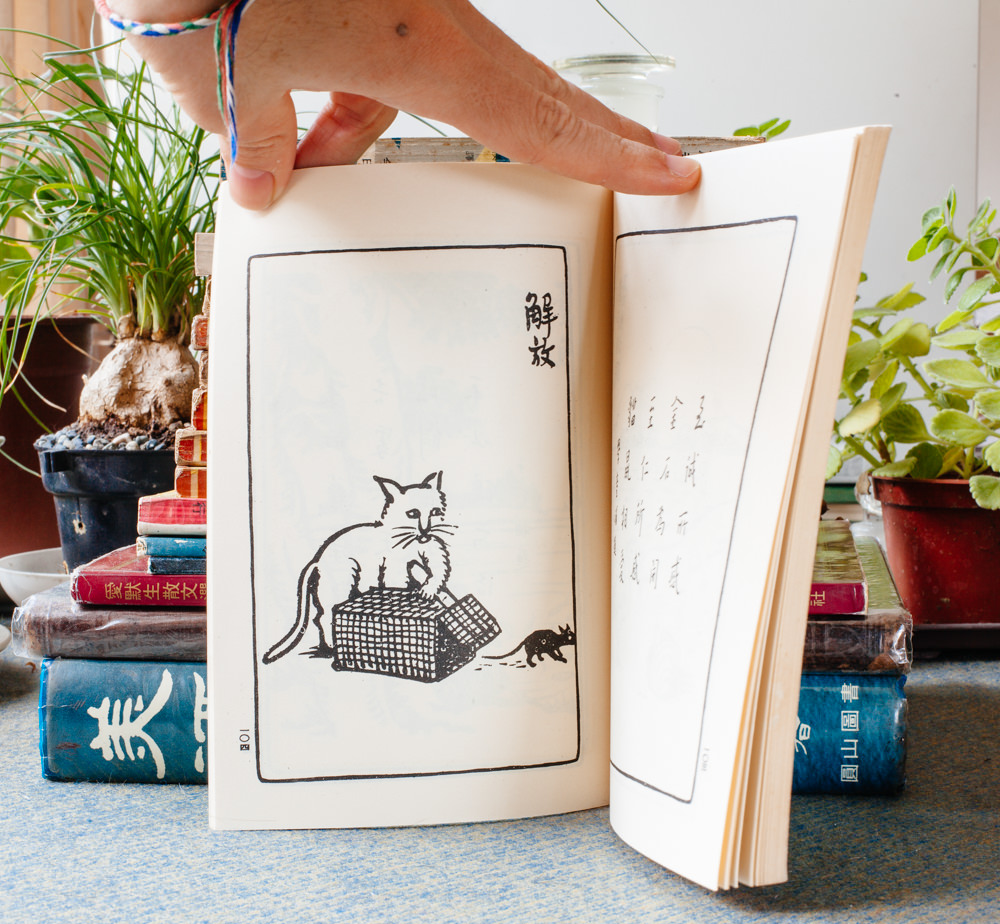

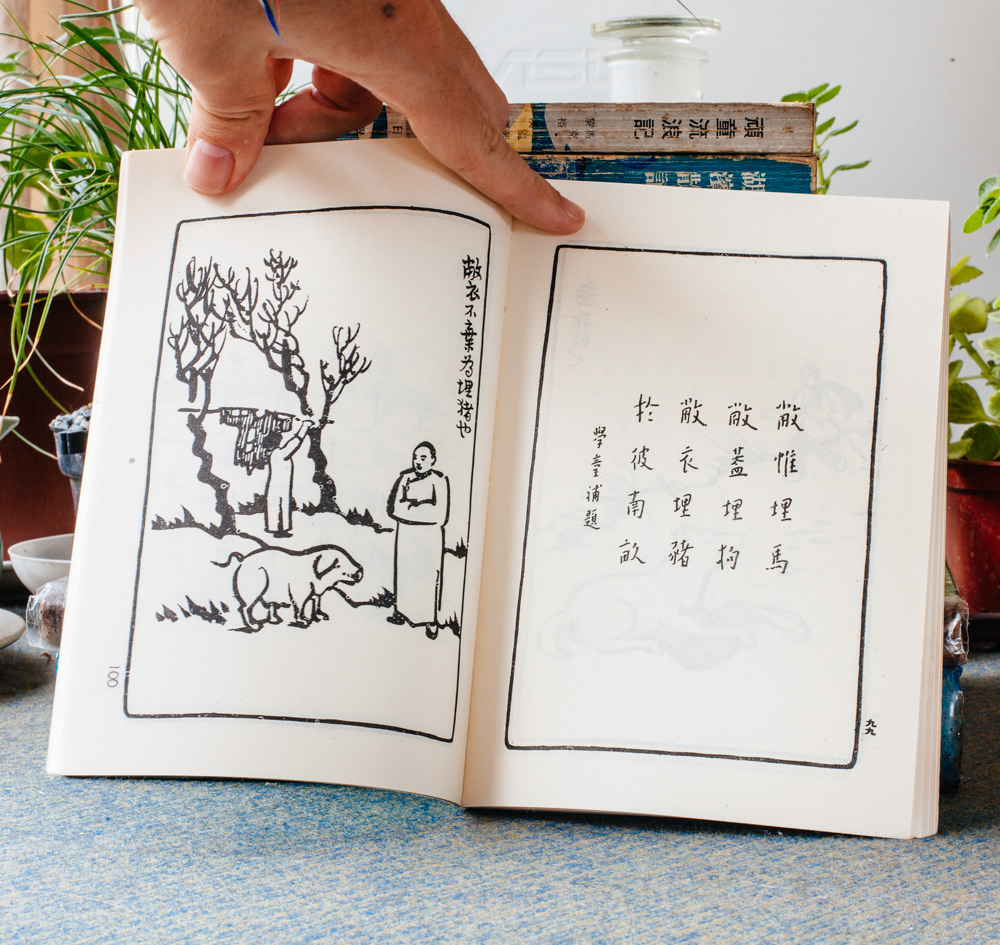

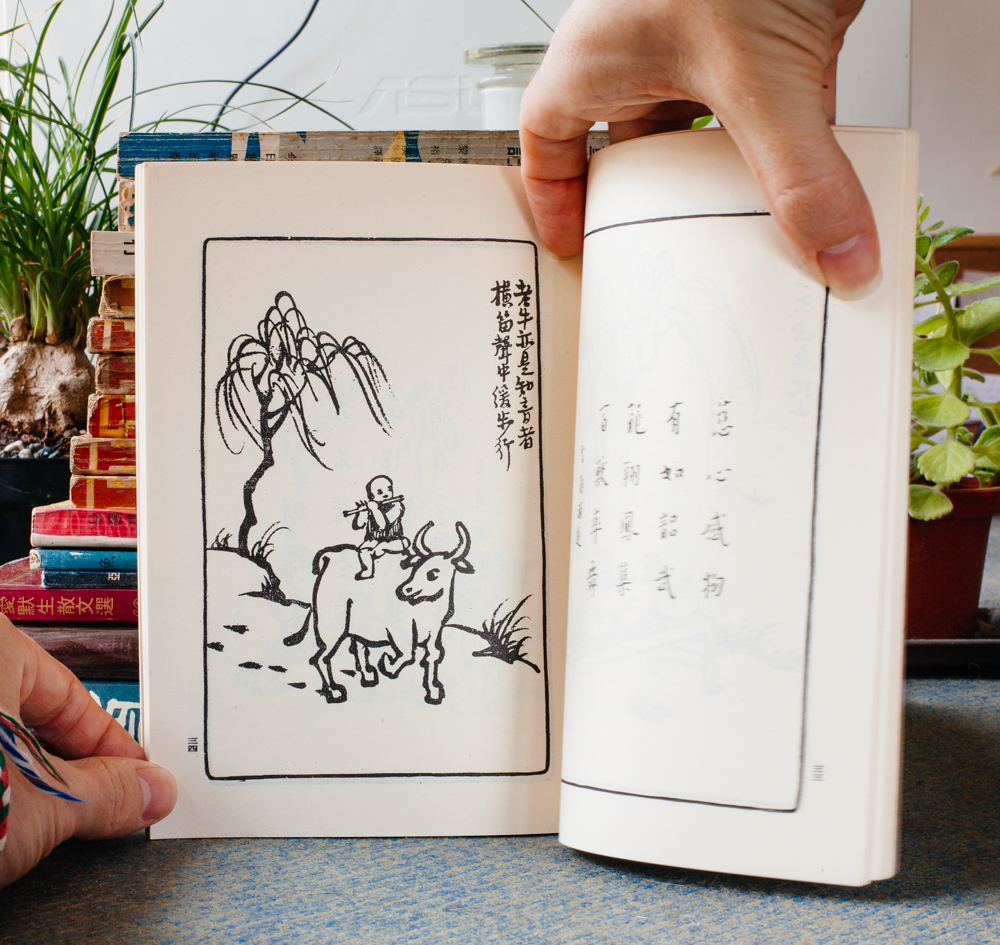

Paintings on the Preservation of Life (Vol. II) by Feng Zikai (I will write more about him, one of my favorite 20th Century Chinese writers/artists, at a later date.)

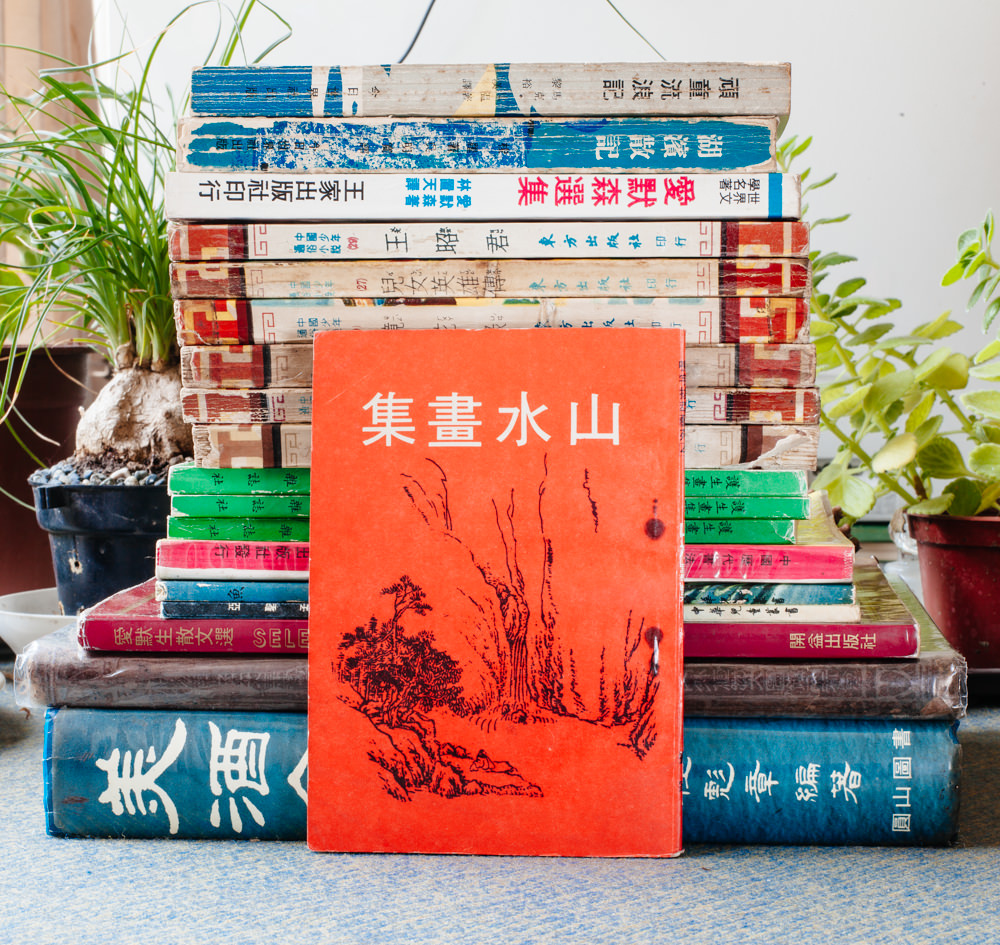

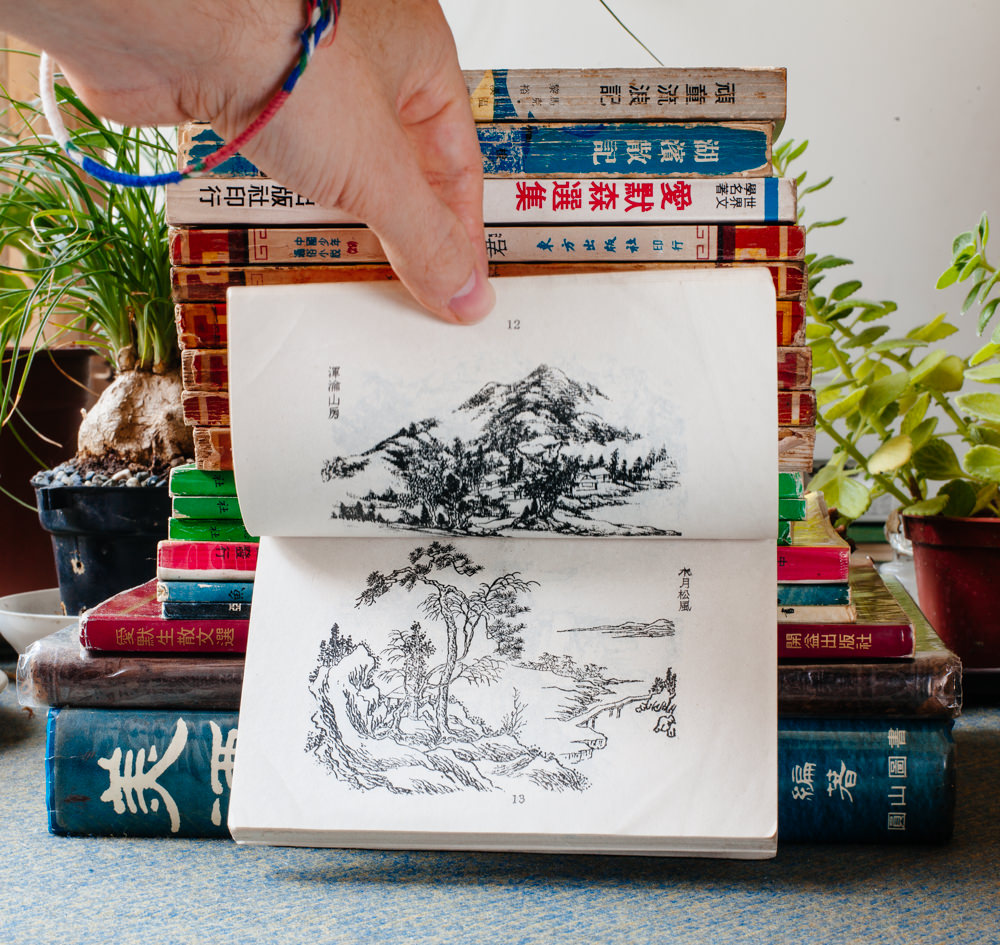

Collection of Landscape Paintings

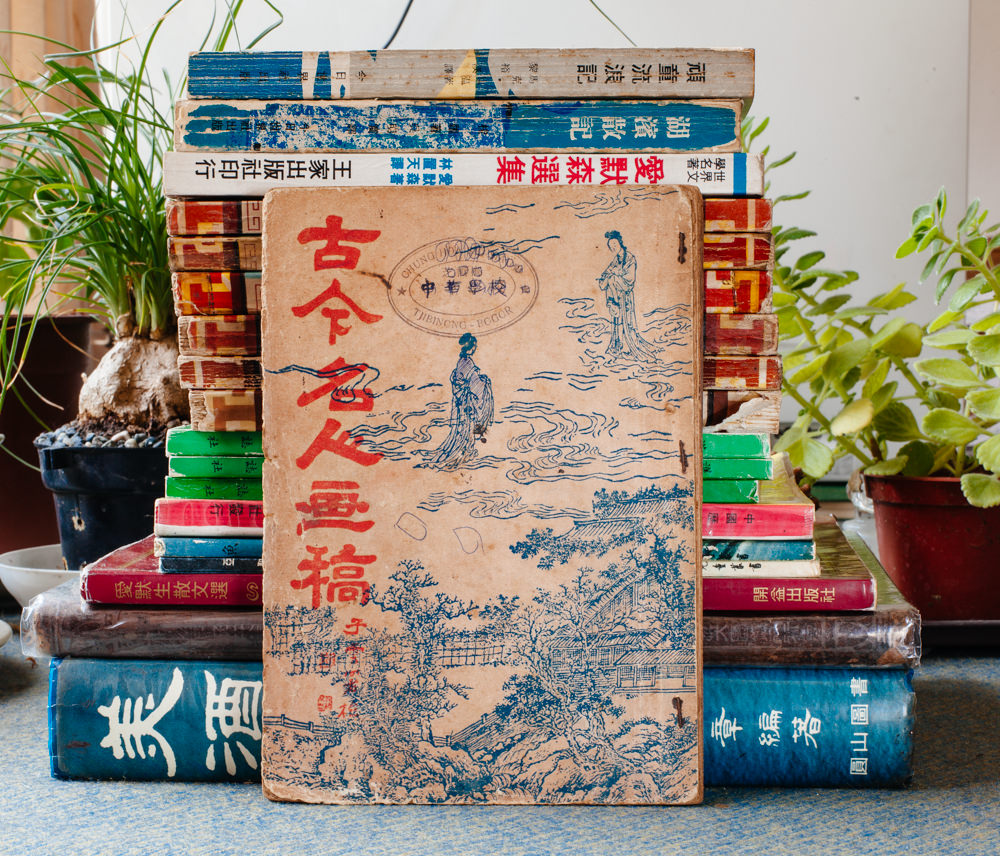

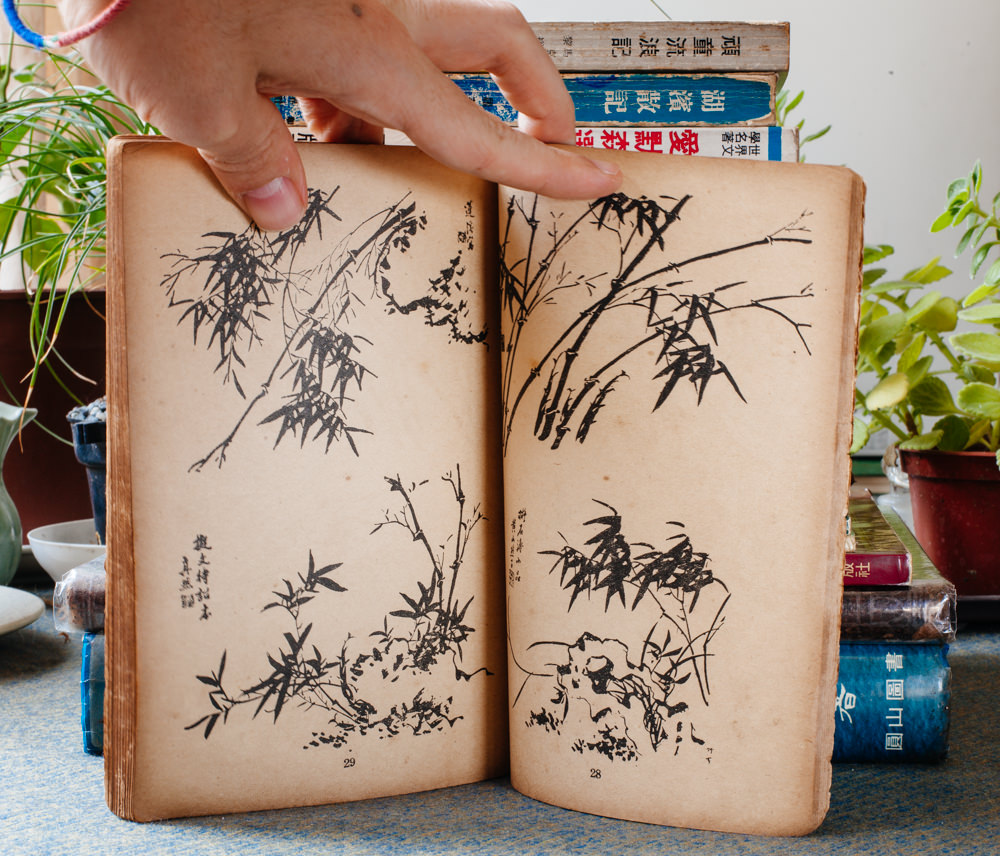

Manuscripts of Classic and Modern Artists

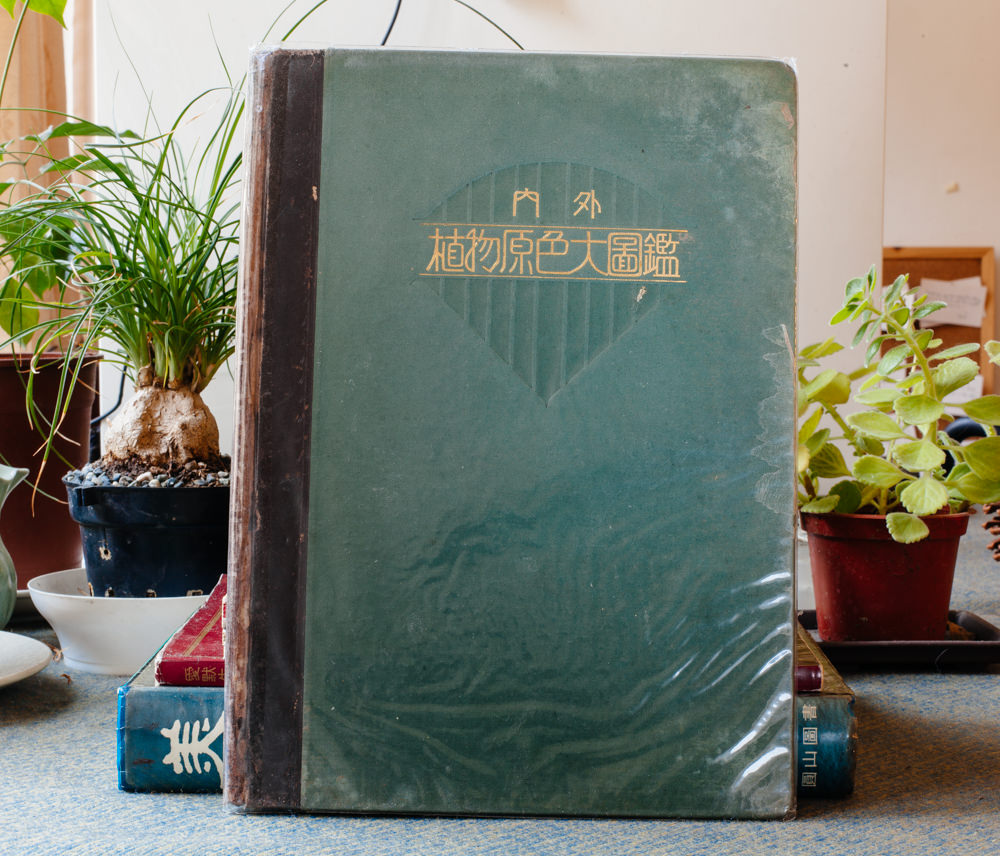

- Original Color Picture Catalog of Plants

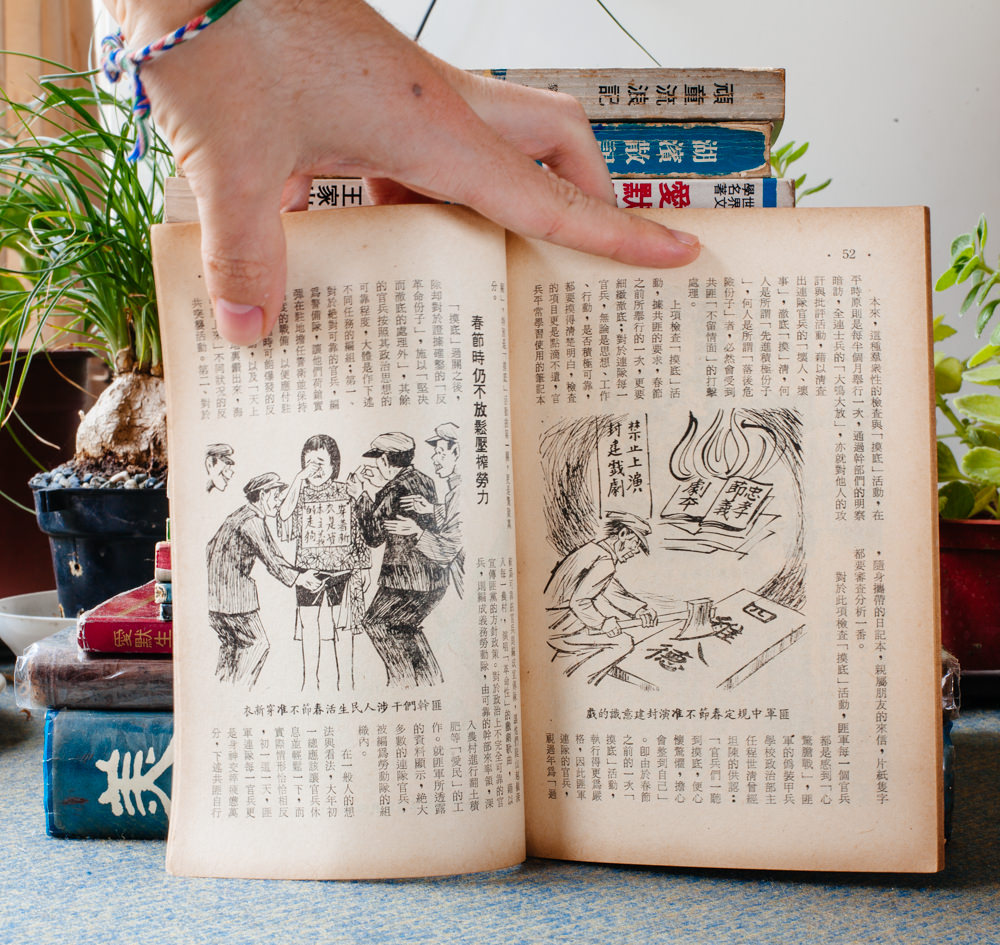

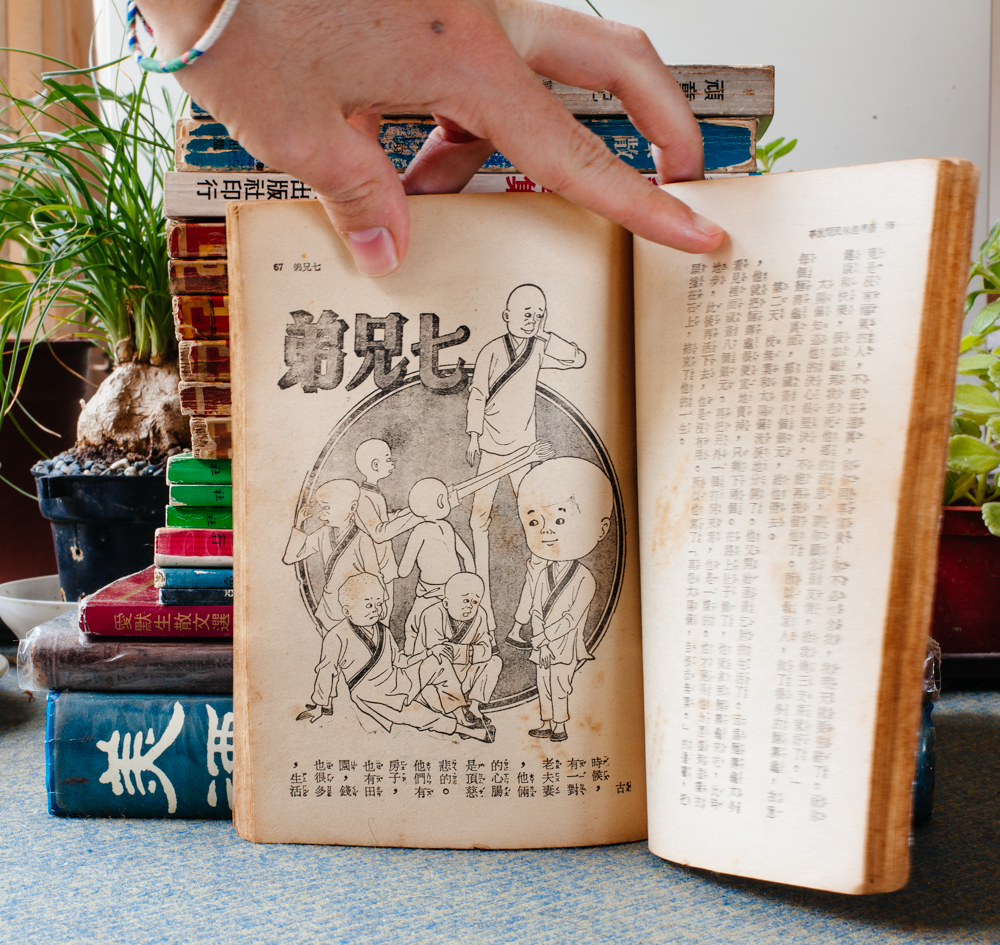

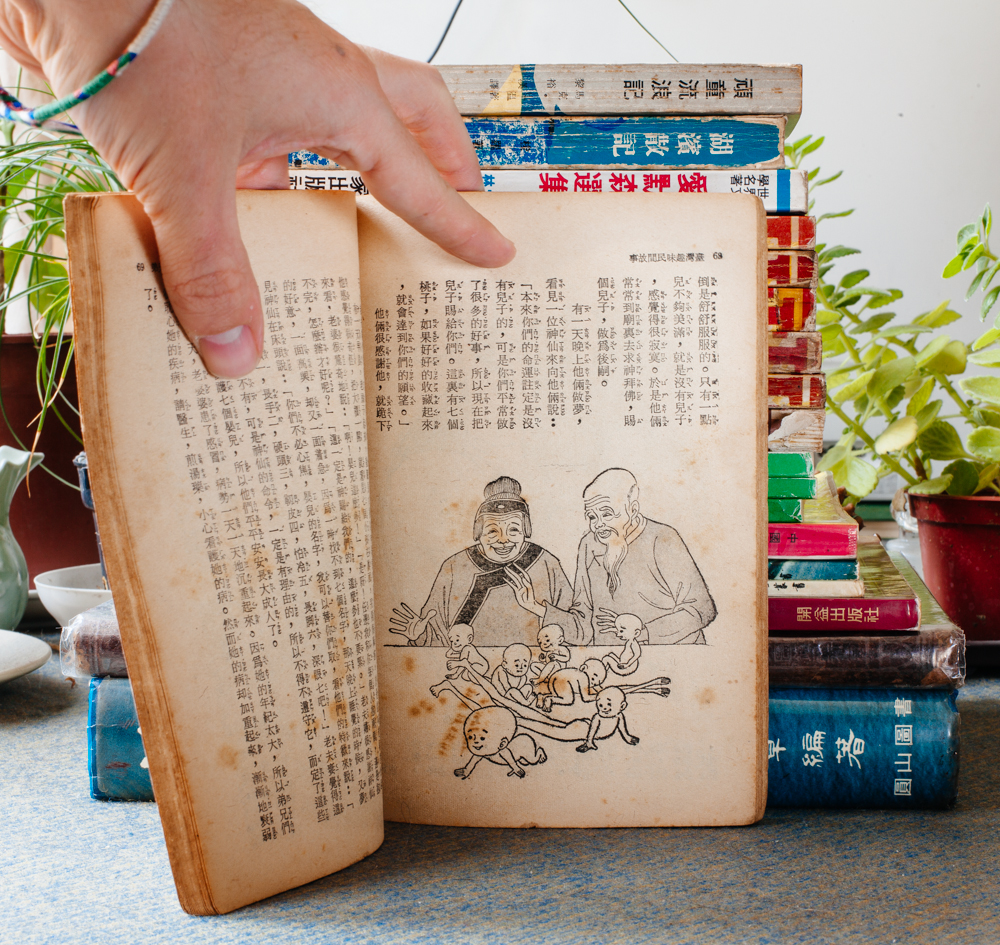

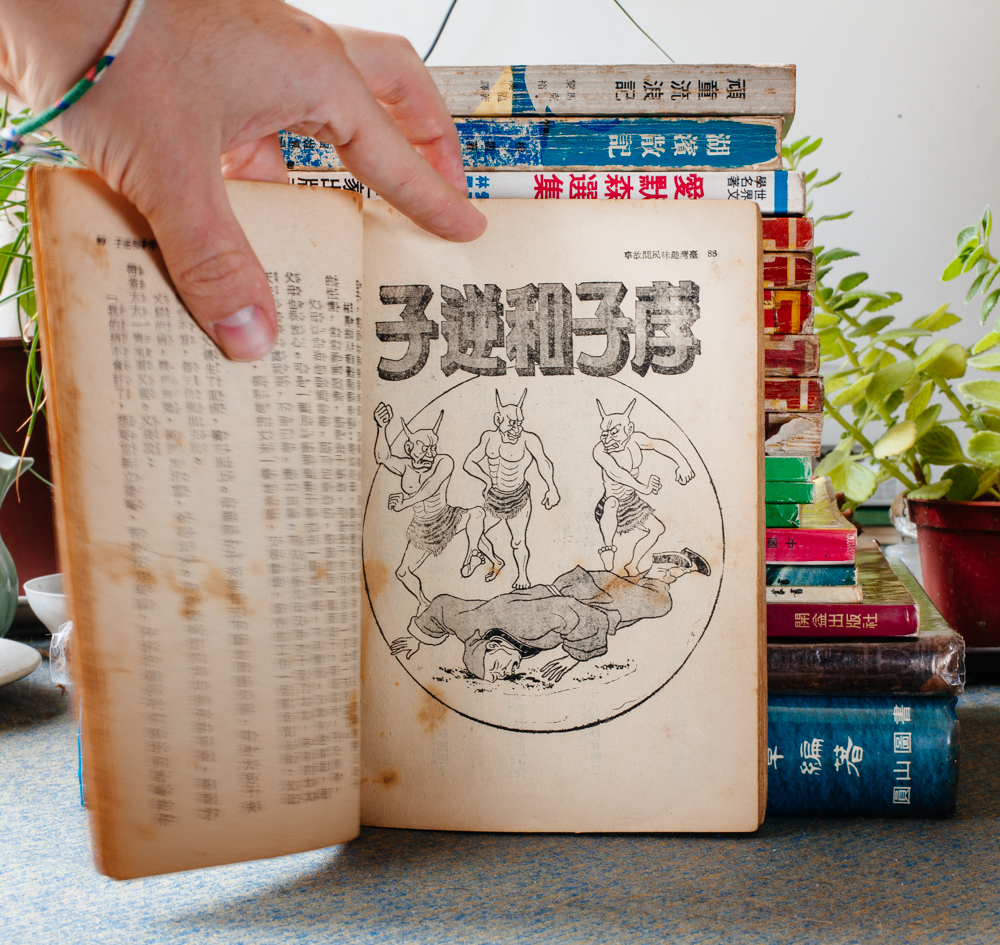

The Strange and Fun

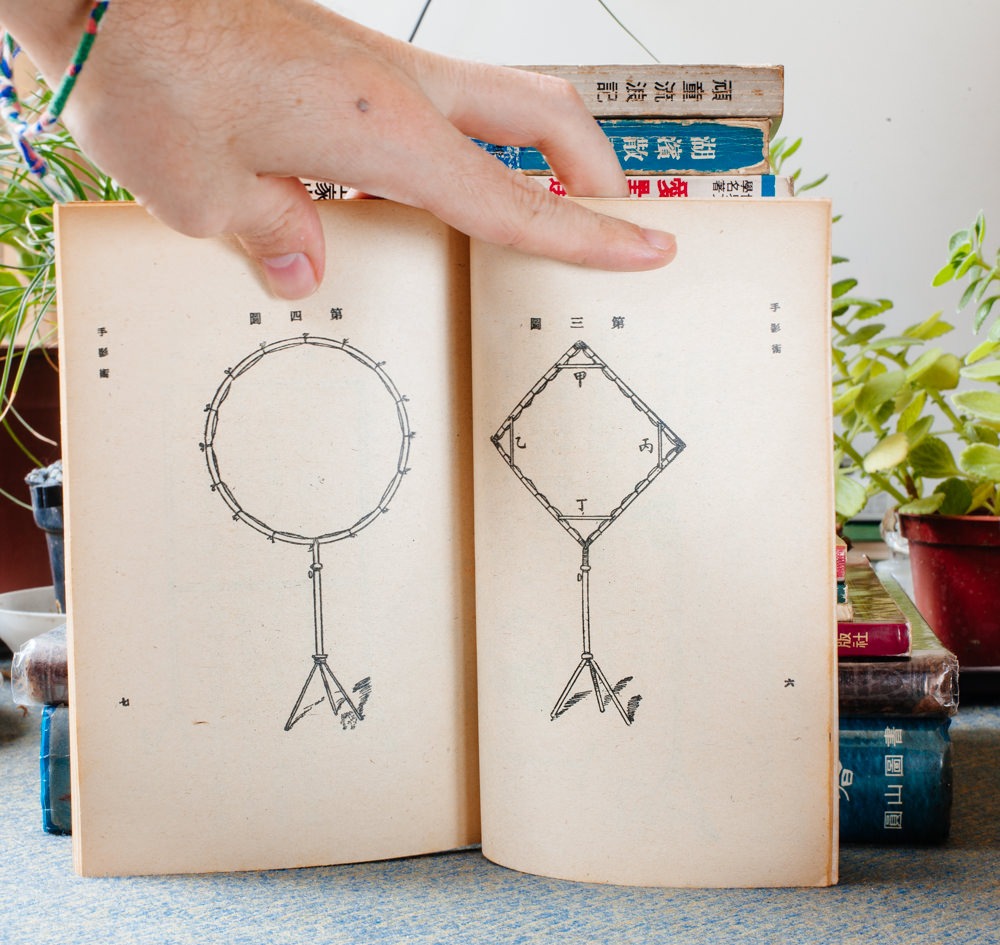

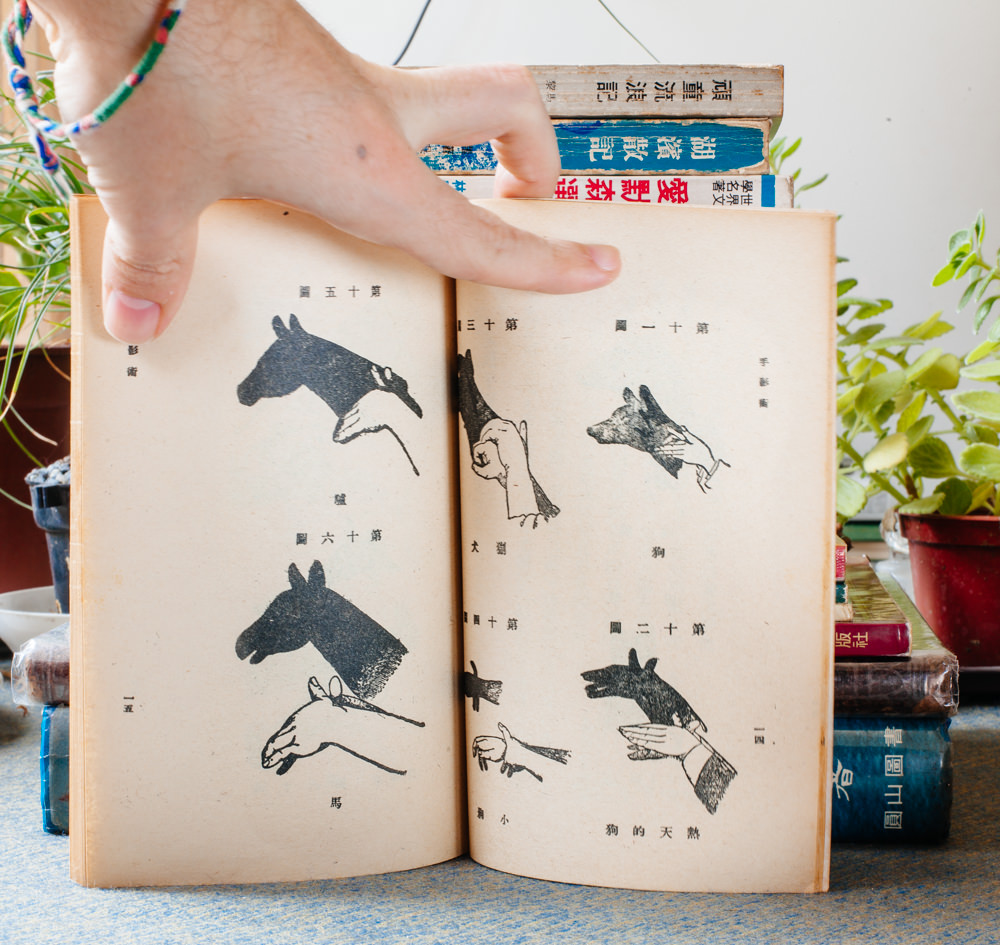

The Art of Shadow Puppetry

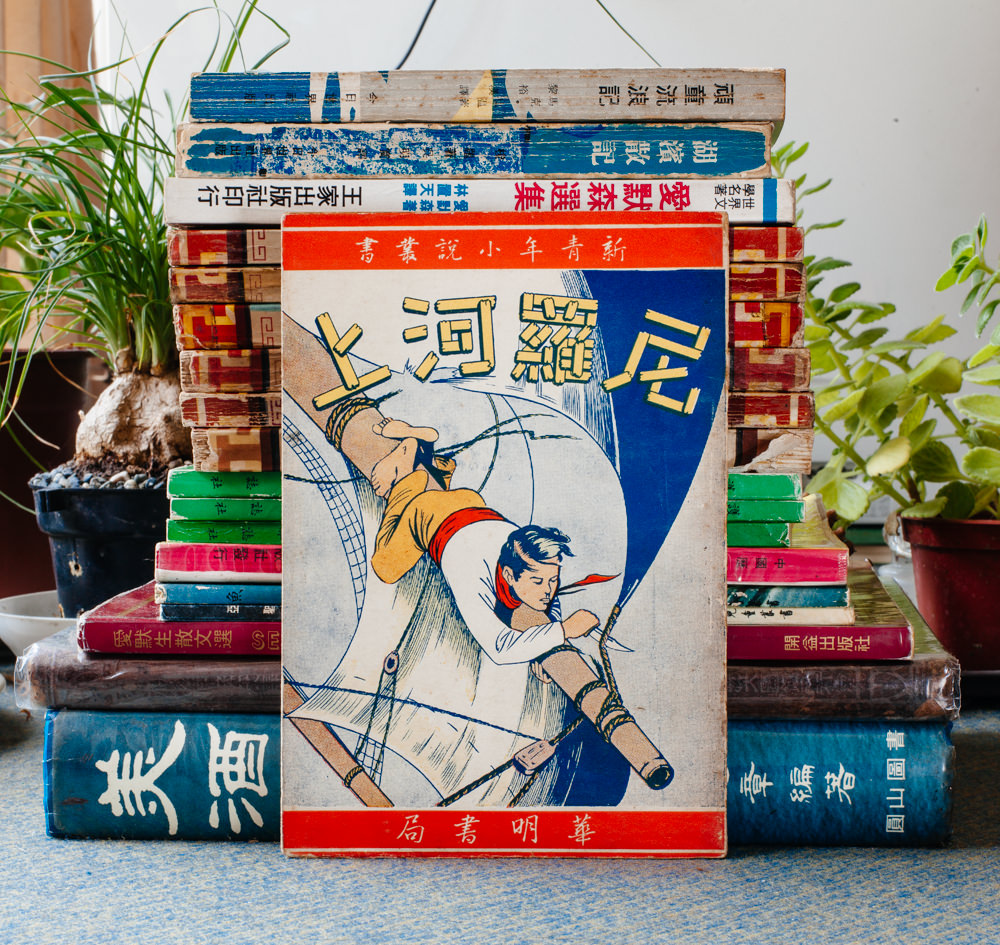

On the Nile River

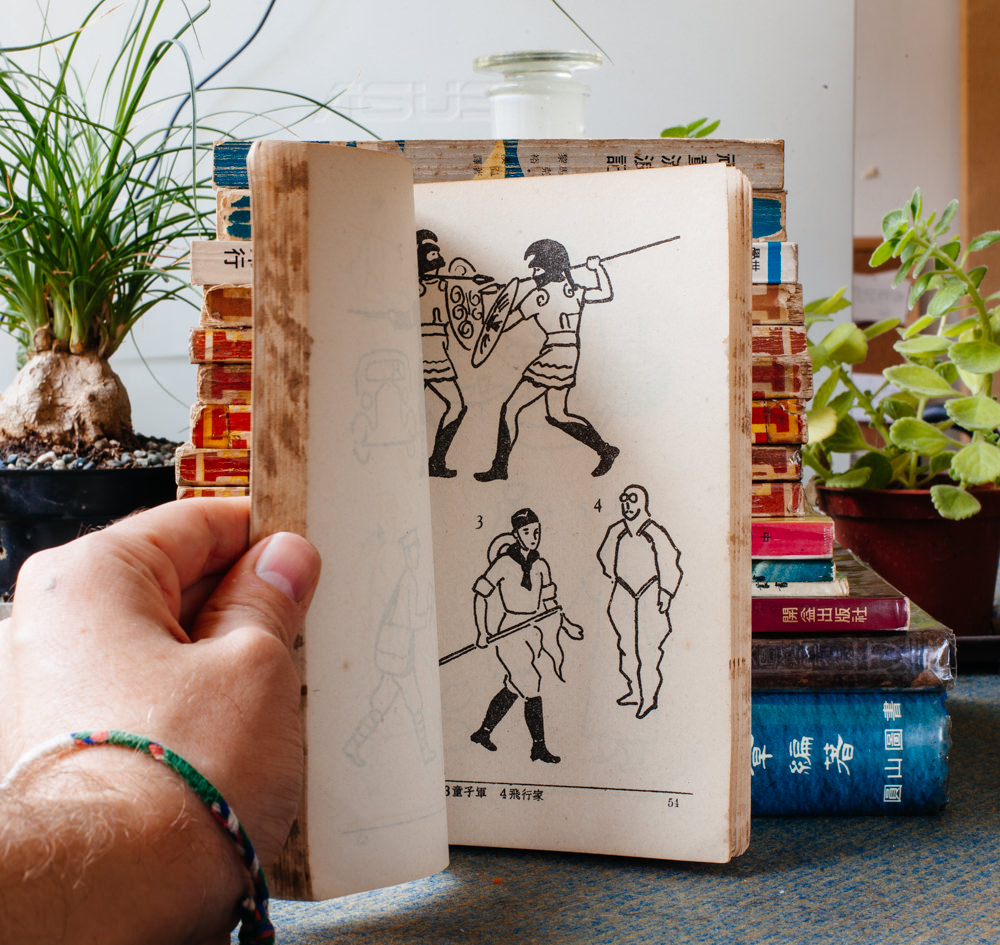

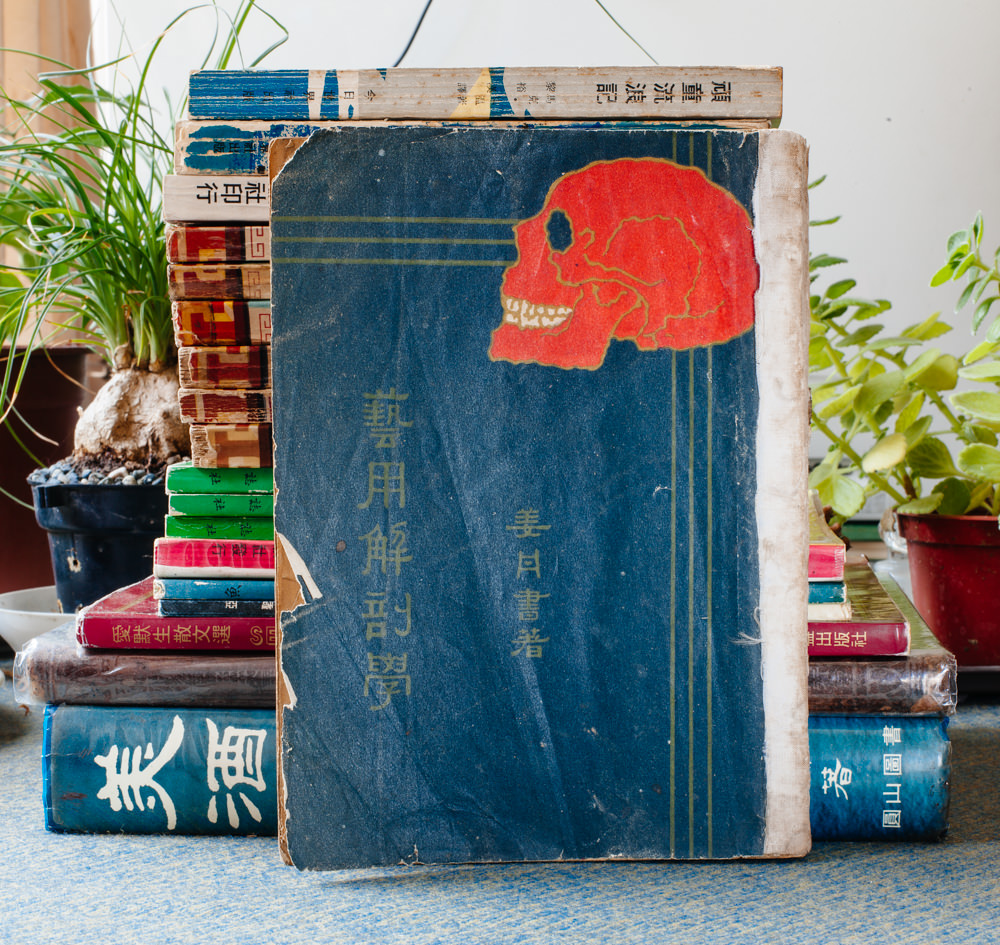

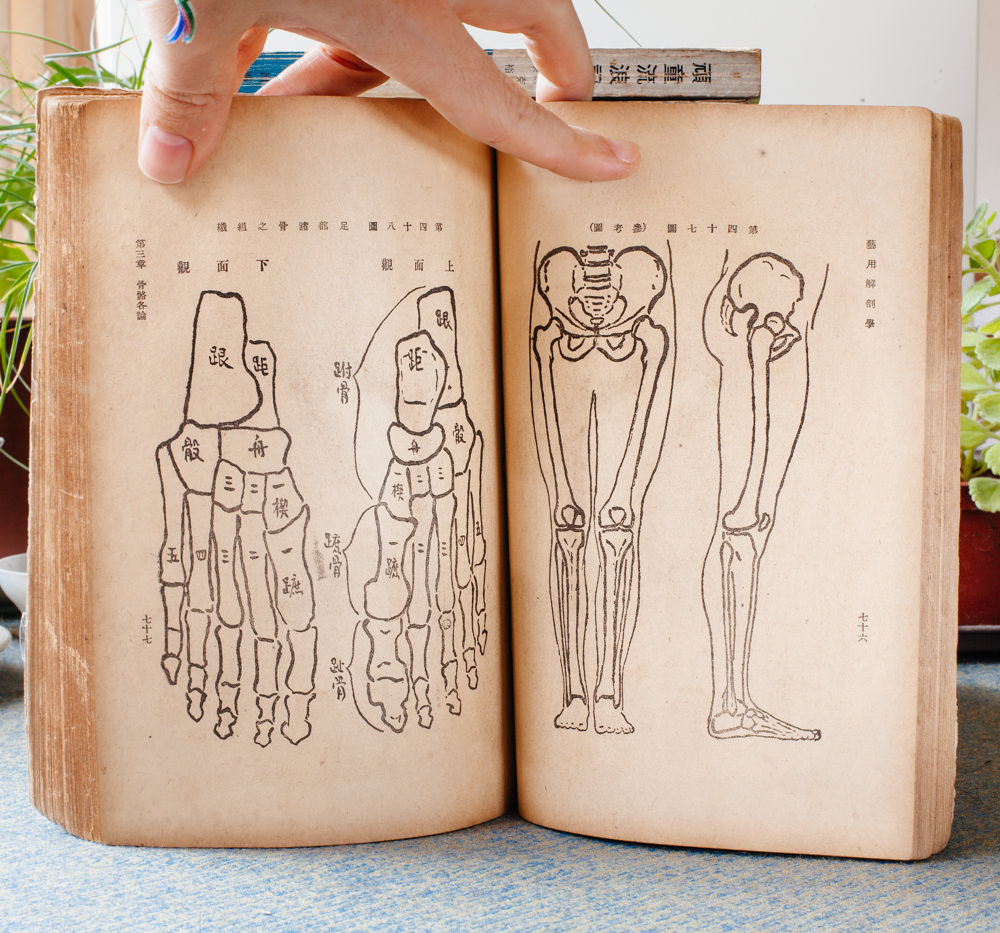

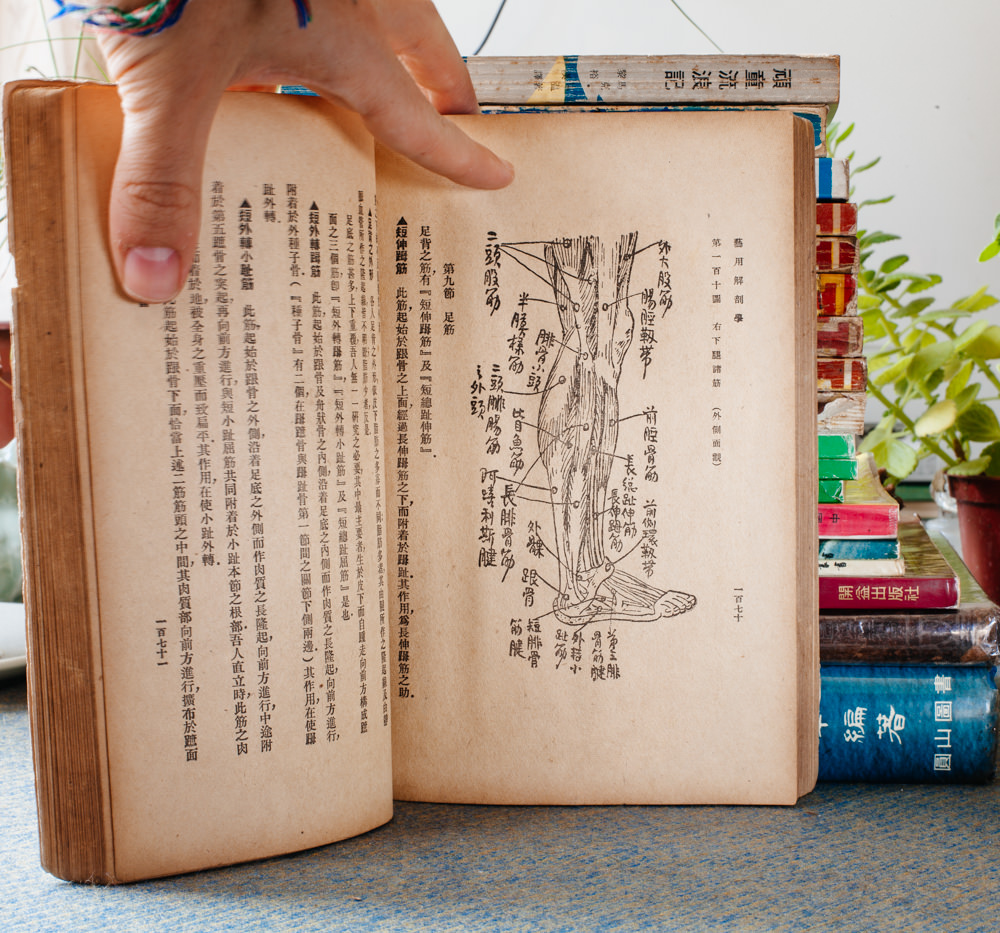

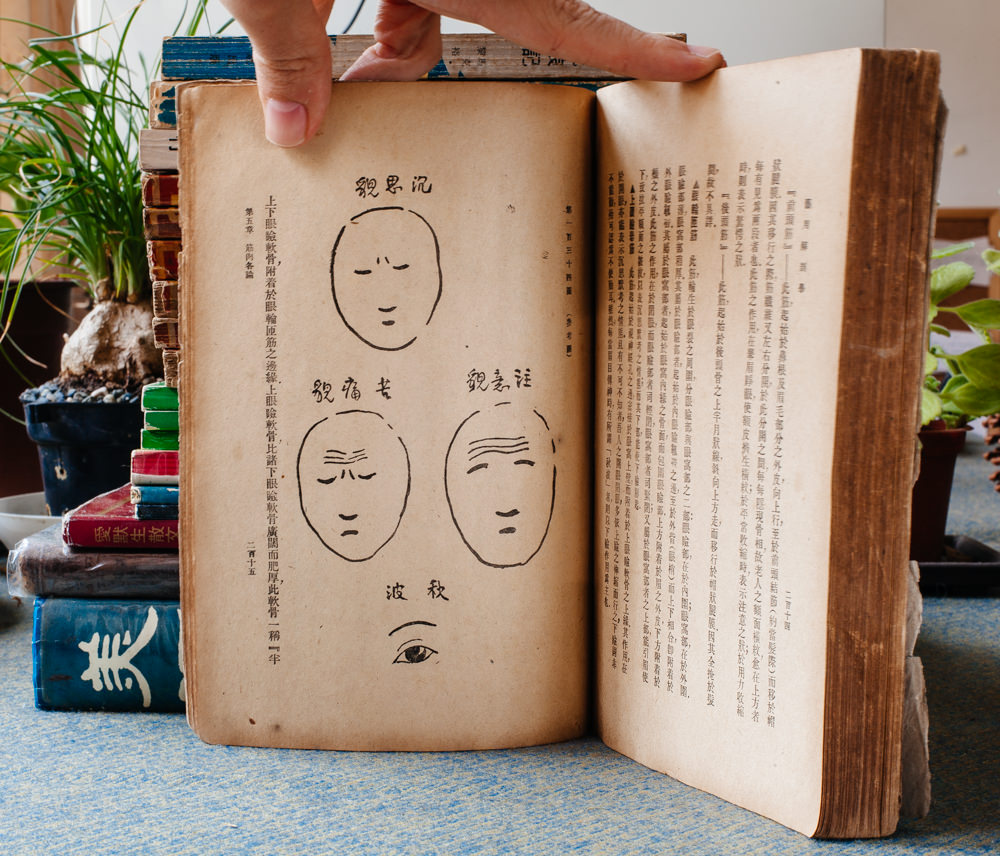

Anatomy for Artistic Purposes

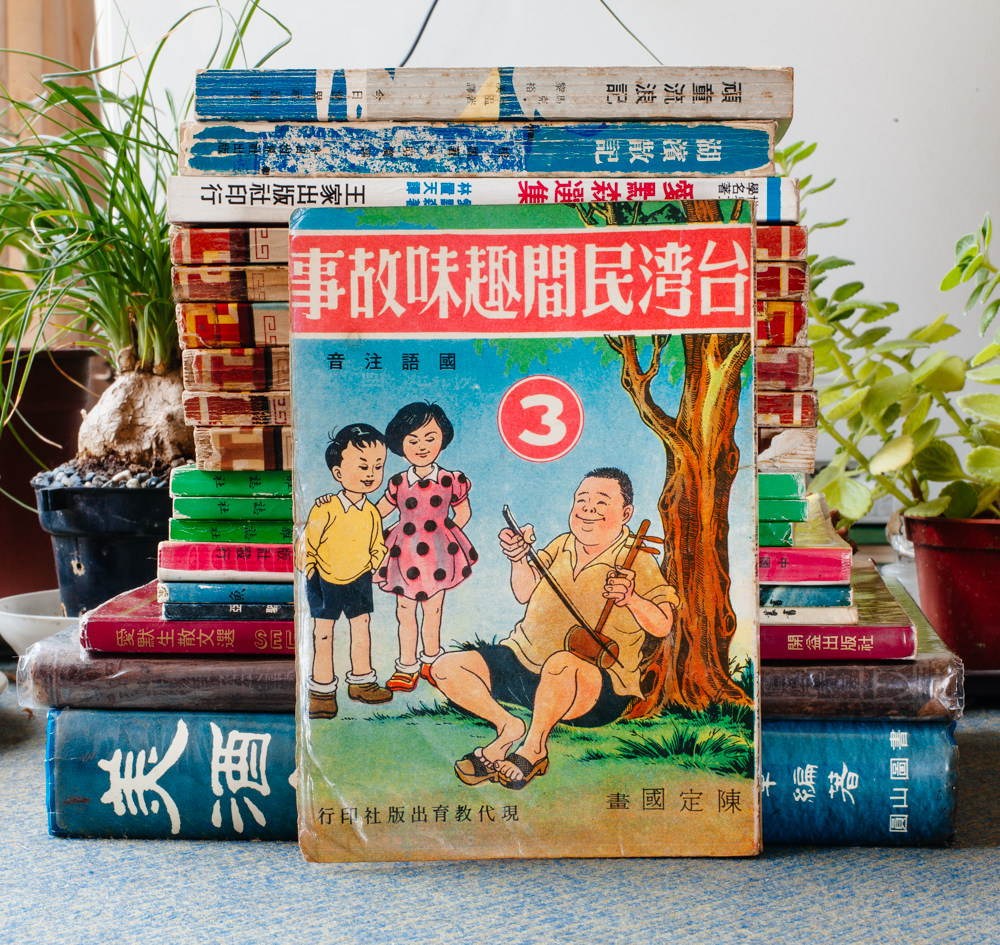

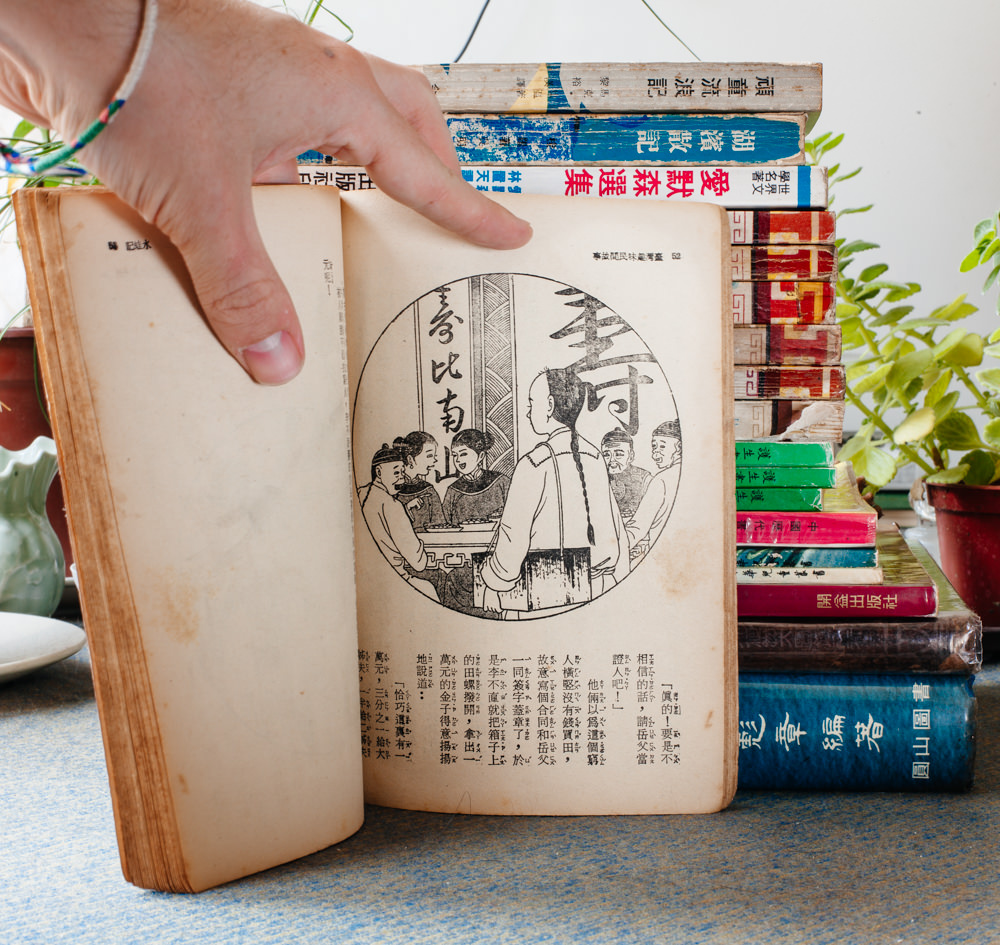

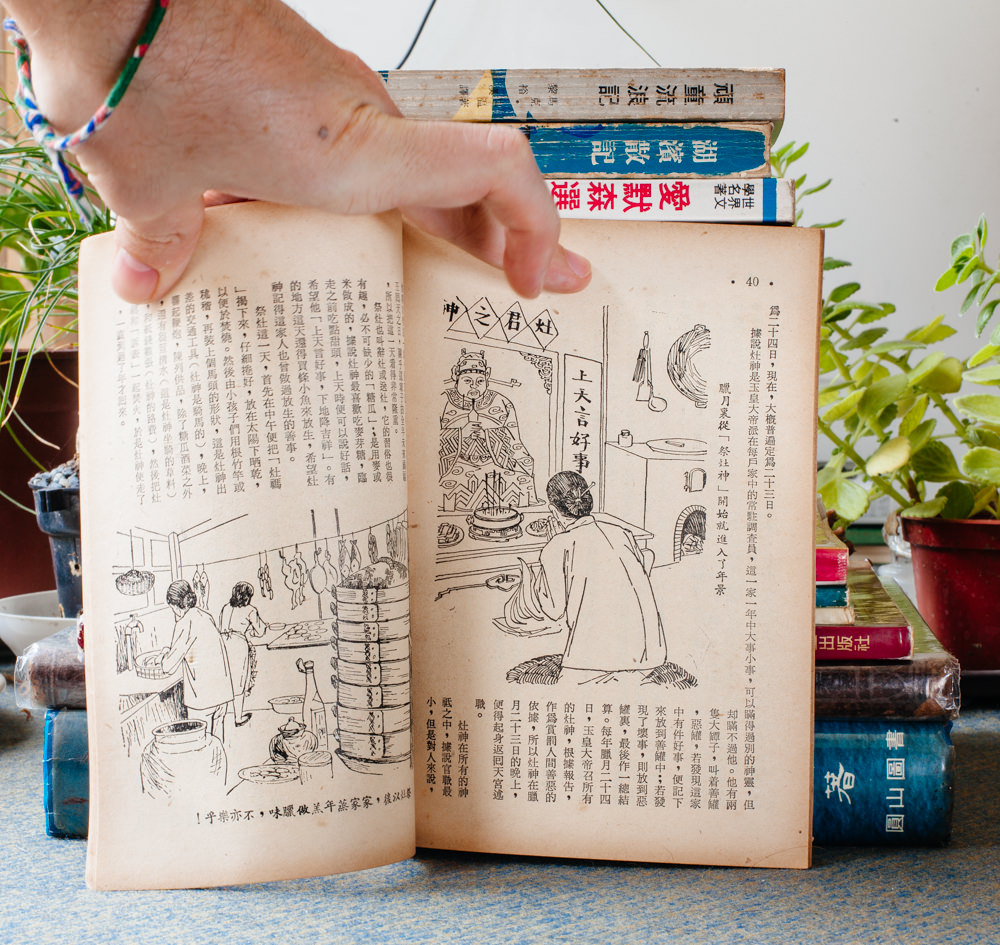

Delightful Folk Stories of Taiwan

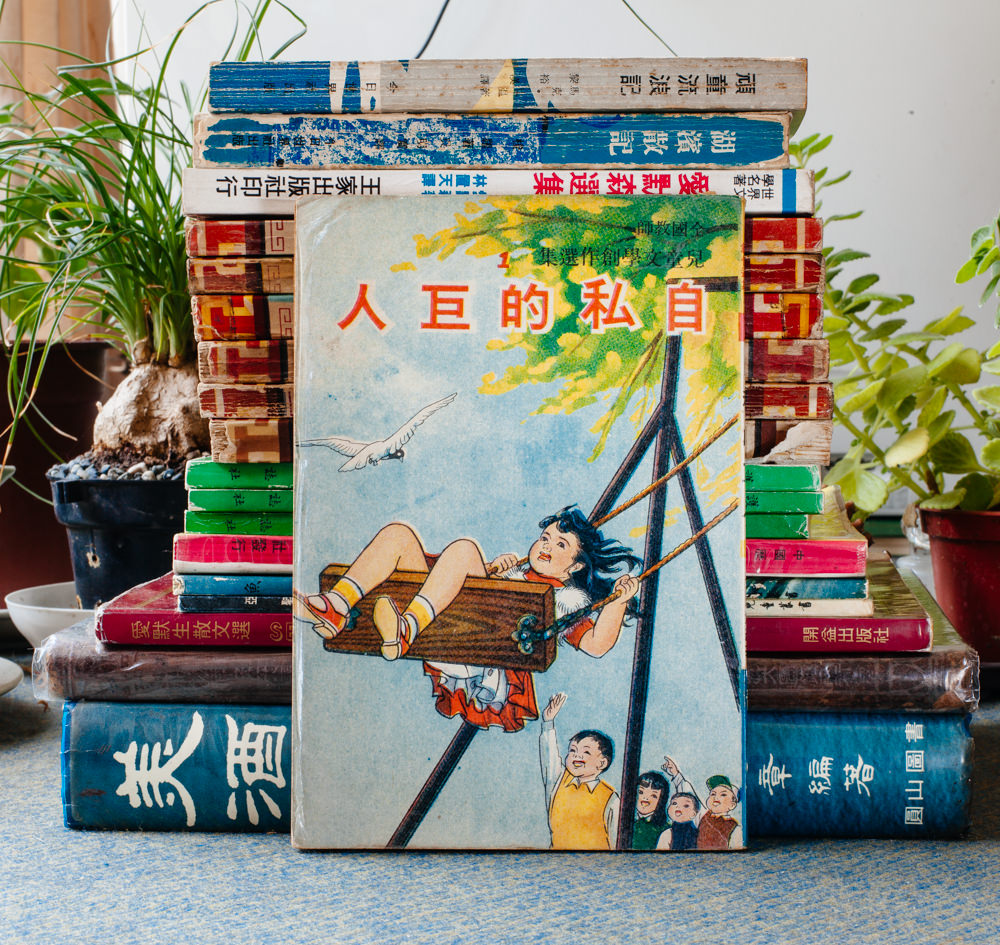

Excerpts from various children’s books

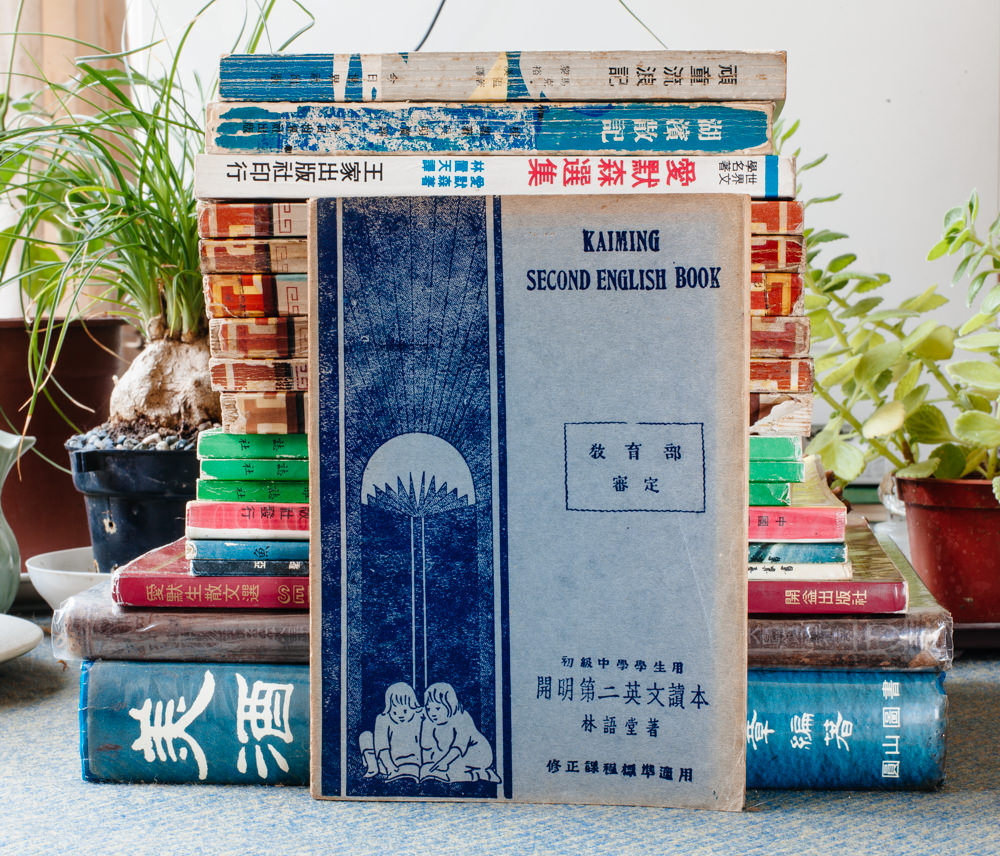

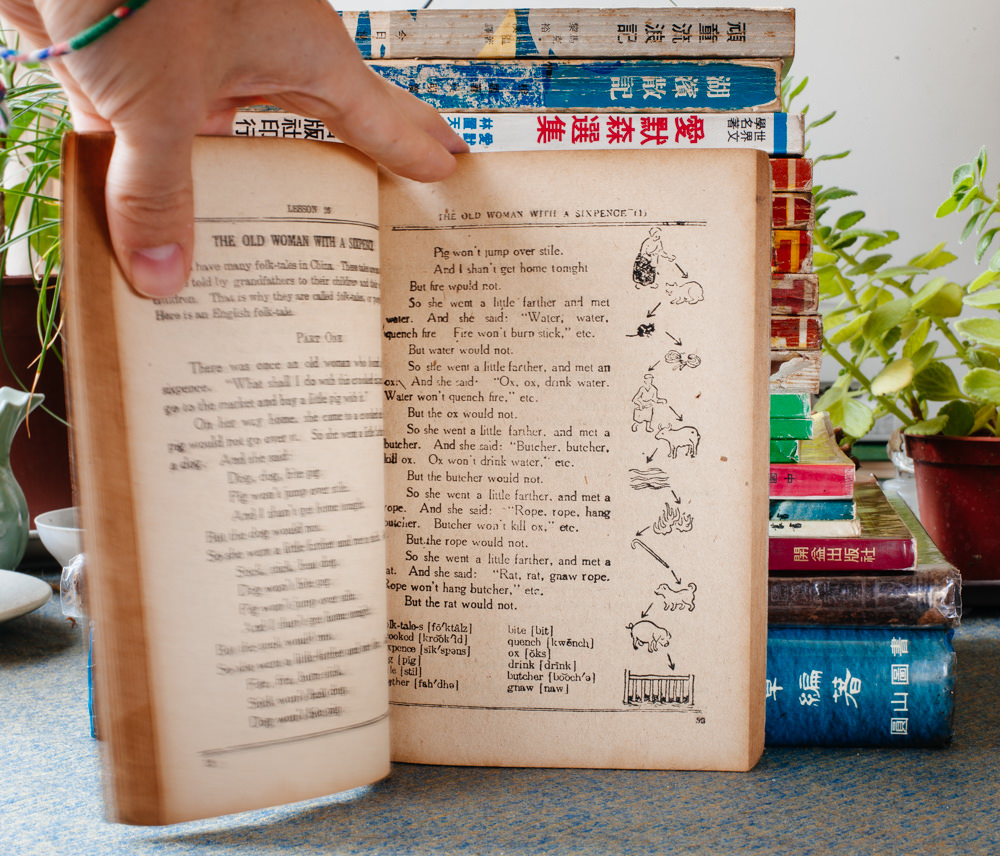

Kaiming Second English Book (This primer was written by one of the most important literary figures in the Chinese speaking world at the time, the Harvard graduate Lin Yutang. Curiously, it was also illustrated by Feng Zikai, who has another selection above)

- Ji RueiTong

For the Kids

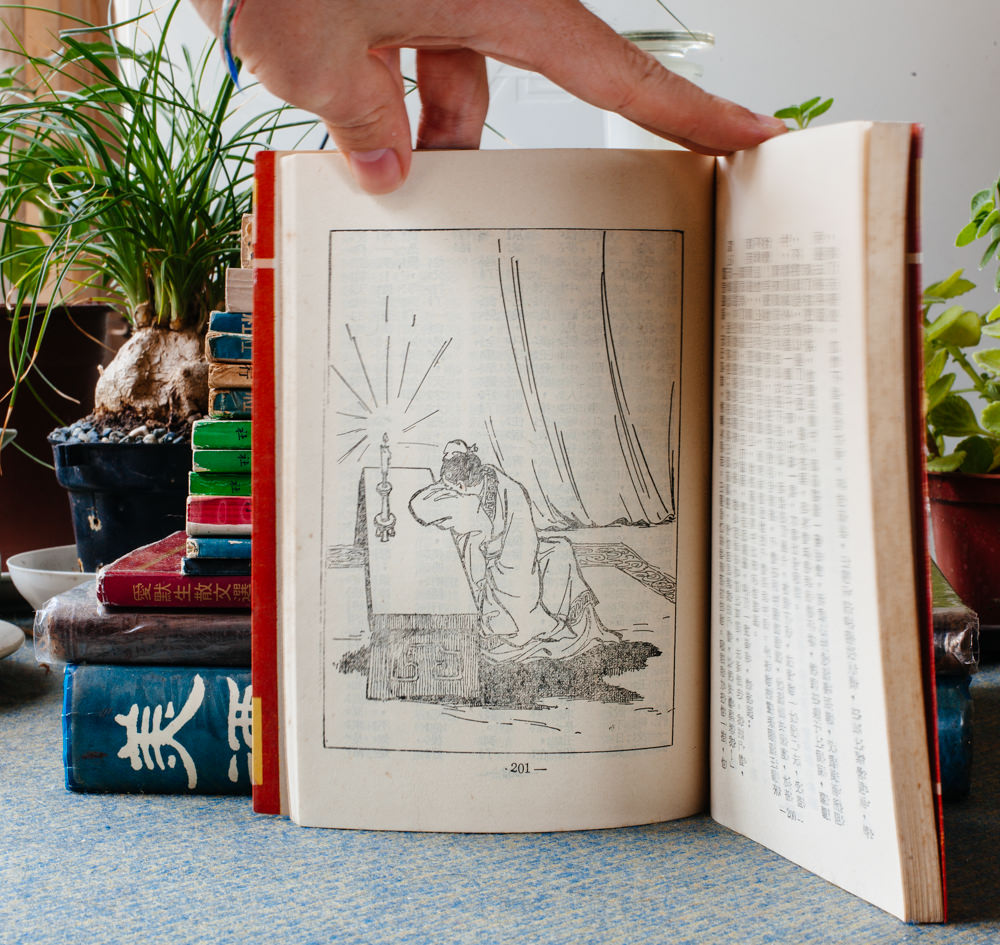

The Case of Shi Gong

The Selfish Giant

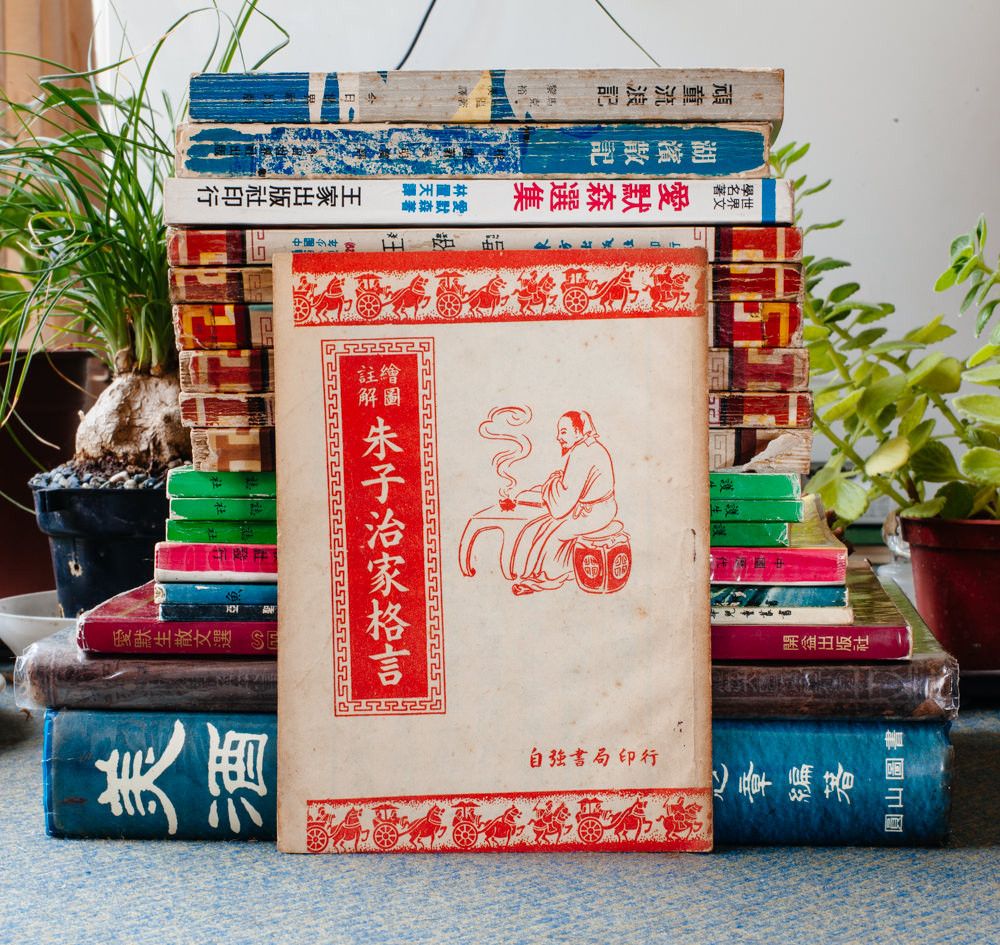

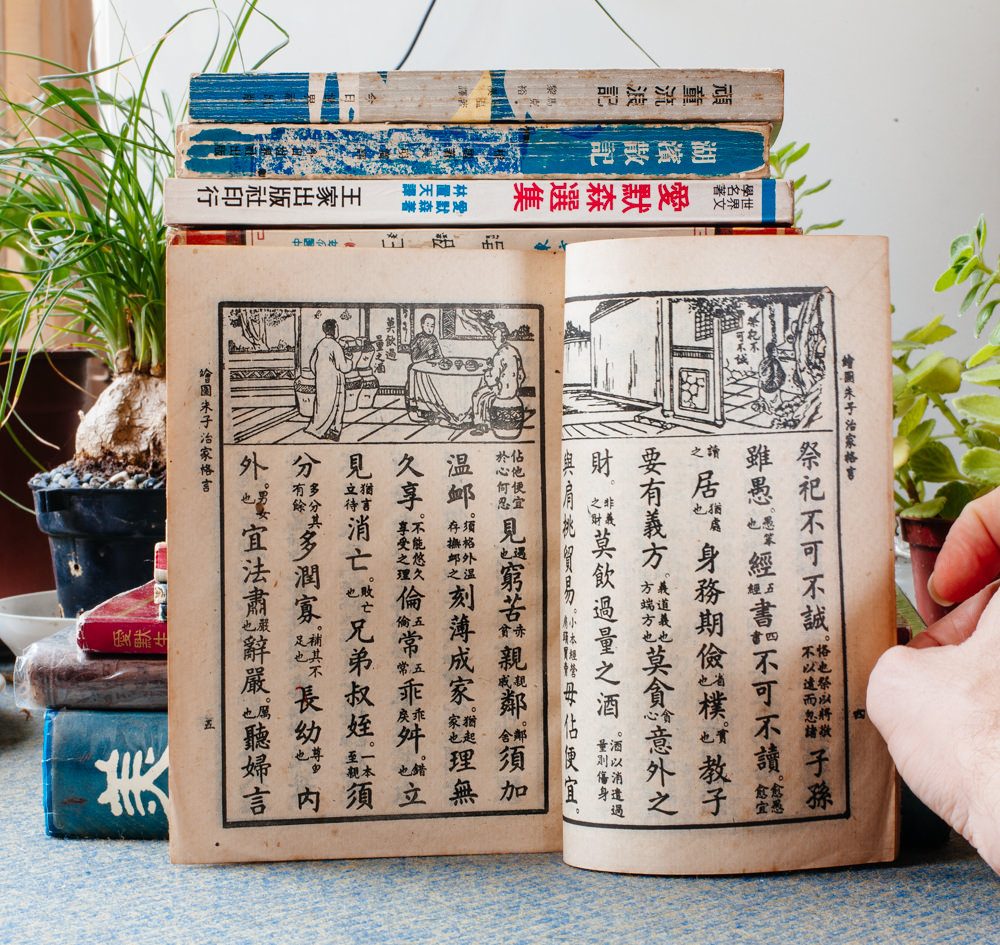

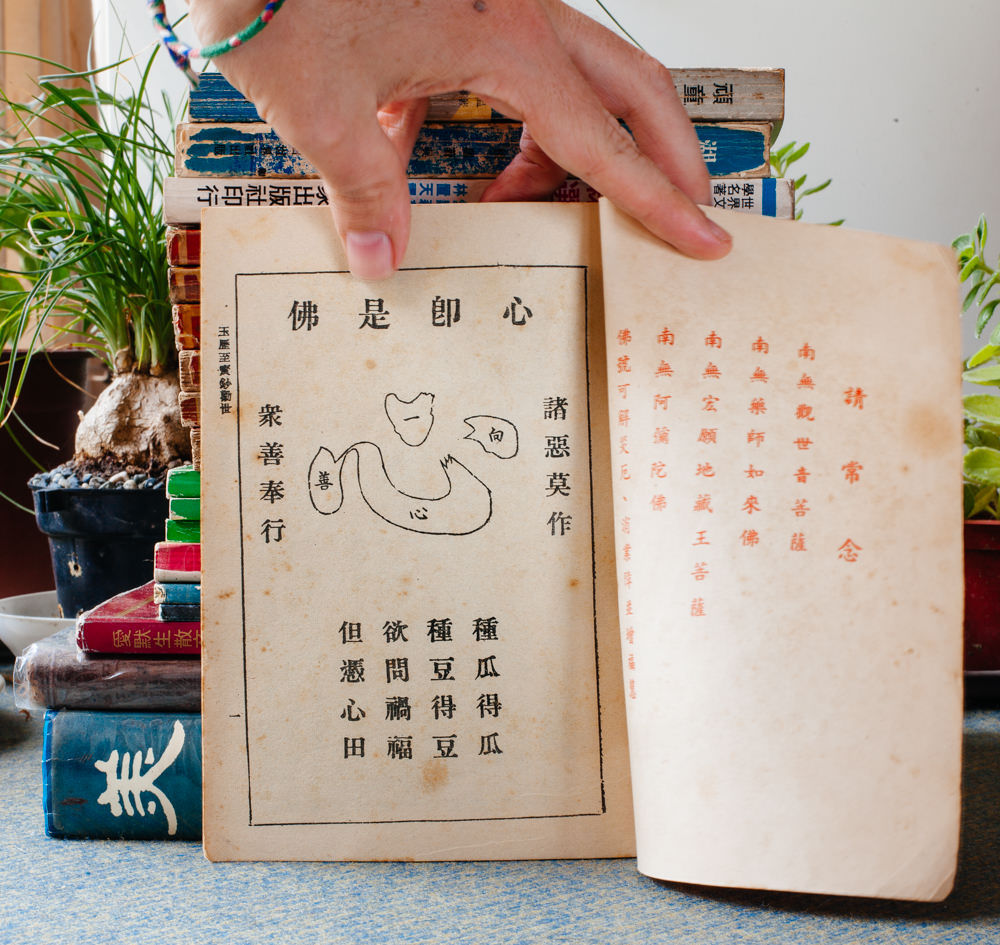

Master Zhu’s Family Doctrines

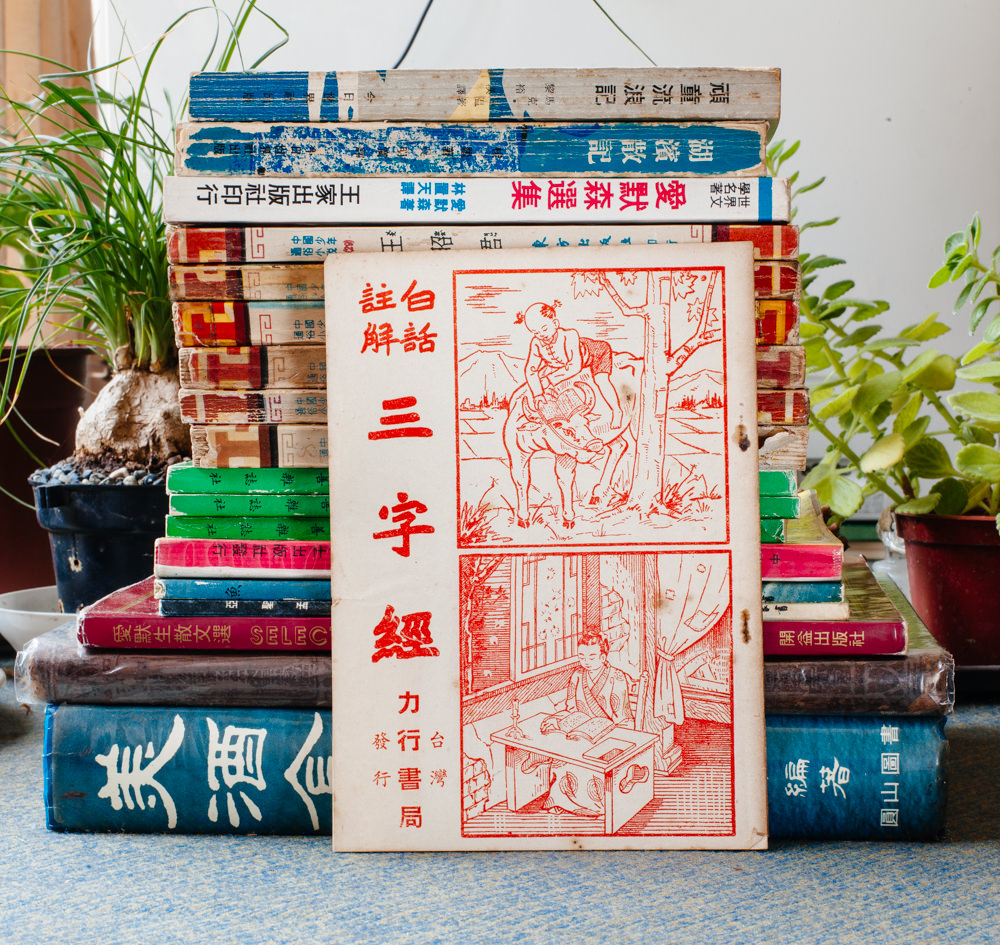

- Three Character Classic (Most likely written in the 13th century, this is one of the most important educational texts in Chinese, widely used in Taiwan up till the 1960's. It's an amazing feat of writing, each line consisting of only three characters and using a wide variety of characters and grammatical patterns to make it a useful tool for children learning the written and spoken language. In addition to its use in language education, the text also neatly sums up the entire world-view of Chinese Confucian thought, helping to indoctrinate numerous generations of Chinese children. The very famous opening lines illustrate a line of thought seen as elemental to later Confucian orthodoxy, as explicitly stated by Mencius. The lines are:

人之初 (rén zhī chū) People at birth,

性本善 (xìng běn shàn) Are naturally good (kind-hearted).

性相近 (xìng xiāng jìn) Their natures are similar,

習相遠 (xí xiāng yuǎn) (But) their habits make them different (from each other).