Here are new photographs from 2016/2017 that will be added to What's Out There.

[p] Motorbikes

[g] Don't Judge a Book by its Cover with Linda Huang

When choosing a book to read, “Don’t judge a book by its cover,” was the elementary school teacher’s mantra. Seen by the teachers as a necessary warning against the over-simplification and miscategorization of a piece of literature, it may have been more accurately quoted, “Don’t judge literature by its cover.” That is because the book, by definition, is a physical thing, one that exudes various amounts of influence on the text inside based on a great many things including paper selection, size and type choice (this is to say nothing about the book’s standalone value as an object). Out of any of its characteristics, the design of the cover may exert the most power. Some writers and publishers see this as a responsibility or an opportunity to illustrate aspects of the text. Some don’t care. And yet, no matter how we weigh the necessity or role of the design (or lack thereof) of the cover, our sense of sight — that first perception — is highly likely to be the first impression we have of a book and the work inside.

Reading literature is a slow burning and time-asking activity. Selecting a book is, oftentimes, a much faster activity. Covers catch our eyes and invite us to look a little bit closer. They can also aid the book, as it is often the text’s only “picture.” Images that initially serve only as an impetus for an experience in literature or art can become ingrained in our mind — they can color feelings and influence thought. And even more recently, with the rise of the eBook, the book cover is not a physical/protective necessity — it is simply an image — an advertisement for the book.

In the face of these thoughts and the changes wrought by our advances, I wanted to go a bit deeper into these thoughts and see what came out. To do that, I contacted my good friend Linda Huang.

******************

Linda Huang is a book designer for the Knopf Publishing Group. When I first learned of her new position at the firm, I was somewhat envious; of the many job fantasies I have, designing book covers has always been among them. The lettering of George Salter, the cloth-work on early Mark Twain novels, and Peter Mendelsund designs have, at various times, had a significant hold on my imagination. And yet, Linda, a student of the humanities, actually developed that dream and has made large strides and a great impact in one of the most influential publishing houses. Her designs can be seen at nearly any book store, and, as is more and more common, on the web. So when I had queries, thoughts and feelings that didn’t seem to quite flesh themselves out, I thought I would enlist her to get a more professional and experienced voice to weigh in. When I proposed to Linda that we do a long form interview to answer those questions, she instantly agreed. The following is our conversation.

Design: George Salter

Huck Finn's 1st edition

Adam: What is your job title? What do you do?

Linda: I'm a designer at Vintage & Anchor Books, the paperback imprint of the Knopf Publishing Group at Random House. I design book covers.

Adam: What is a book cover designer? What does the job entail?

Linda: A book cover designer is a graphic designer who distills the essence of a book to attract potential readers, or to put it simply, to advertise the book. It's a marketing tool as well as type of visual literary criticism. It doesn't involve trying to summarize the entire book — that would be impossible. Increasingly, I think it means giving the potential reader a sense of what it feels like to read the book. I think the best book covers are designed by designers who like words and enjoy reading. It entails getting to know the material — reading as much as you want or can, and making decisions about what makes sense for the cover. It’s quite a responsibility.

I think you can break it down into two parts:

1. Subject matter: Is it going to be an object? A landscape? A character? Is it more about eliciting a tone?

2. Stylistic execution: Graphic? Photographic? Illustrative? Or all-type? It involves intuiting what feels right stylistically.

Adam: Is subject matter a gut-feeling after reading the material or what does it involve? Also, as a designer with your current firm, what kind of personal freedom do you have to express those choices you make as to 1. subject matter and 2. stylistic execution? i.e. are you the one who gets to make these choices? do you ever talk with the author for additional input? is there direction from the top down?

Linda: It's a bit more hazy than just a gut-feeling. Sometimes, a distinct image will come to mind, other times, I'll jot down multiple ideas and try to execute all of them. Or I might try to explore the same idea in different ways. We are rarely told what to do specifically. But we might be shown comparative titles as a preferred direction. That doesn't stop me from exploring something that satisfies my creative impulses, something they might not be expecting but which may end up being better for the book. When these more unexpected covers get rejected I don’t see it as a loss as they provide an opportunity to grow as a designer. So yes, most of the time we get to make these choices, and I appreciate that sense of agency. We never talk with the author (unless you are friends with the author); everything goes through editorial.

Sometimes, when a book is a "priority title," we'll unfortunately get direction from sellers such as Barnes & Noble. They have the power to dictate how the cover should look. And of course we acquiesce because otherwise they won't buy as many books. Almost always, their direction is purely commercial, so what gets produced is usually a tepid, uninspired, mass treatment for the book.

There are a few editors who might already have a clear idea for the cover. Some authors, too. They might have selected a photograph or illustration or have very strong preferences for certain type treatments.

Adam: In that case, you are just the tool?

Linda: Basically, yes, just an executor. It's not a lot of fun, but you can't win every battle.

Adam: I think of the selflessness of a craftsperson doing a job for hire, versus the creative work of an artist, working to express emotions, and in some ways, I see book design as a somewhat fascinating mixture of the two. Do you see this as a balancing act? or is it truly dependent on the job?

Linda: Yes, I think it's definitely more of a balancing act for certain literary fiction, maybe even skewed more towards the “creative work of an artist,” especially for books that are high-concept or classics. Reading is inherently personal; each designer will take away something different and inject their own viewpoint. There is a certain selfishness that comes from the need to express your point of view, compared to, say, a designer of infographics. The balancing act is about making what you find special understandable on the market.

Linda's design for Seven Days in Syria

Adam: Would it be wrong for me to assume that your employer wishes you to use your creativity and that was the main reason reason they hired you?

Linda: I don't think that's wrong to assume. They also hire you for your typography skills, and above all, good taste. Being creative is a boon for certain books that call for a unique look. Other books just need to get the message across clearly. Of course, each book should be unique, but you won’t believe how many times a more unique treatment gets shot down because they don’t think it will translate to the targeted audience.

Adam: Is the main thrust of your design, "how will I make an impression? how will I draw the potential reader in?" Do you feel responsible for that aspect or is that the publisher's job?

Linda: Yeah, I ask myself those questions and I do feel responsible.

I also ask "why would I pick up this book?" and "what do I want to see on the cover of this book?" Designers have an artistic bent and the best ones try to do something different every time, which usually means their work tries to be more original instead of following a formula. Doing the same thing over and over again becomes trite and eventually that type of cover recedes.

I think that at the end of the day, most concepts and subject matters have been used, so it's a matter of how you're expressing it. But, it's very common for publishers to be risk-averse and that's the frustrating battle. You try to do something cool but unsurprisingly, they are afraid nobody is going to get it.

Adam: I mean, I get it — and I think it would be somewhat stupid to entirely trust the designers. No offense.

Linda: [laughs] I understand. Most designers here didn't go to a traditional university or a liberal arts college. . . they all went to art school except for a few, like Peter M.

Adam: But I mean, if it's either too market based or too design based, I can't imagine it's going to succeed on a level except for artistry, if the designer gets their way, or marketability, if the marketing crew gets their way.

Linda: Yup. I mean the practical point is to communicate, and if your cover is too cool or artistic, it's mostly for other designers

Adam: When designing a book, where do you start from, in a philosophical sense? do you have any mantras? rules? prohibitions? things you always have to remind yourself?

Linda: Yes. I panic all the time and feel like I never know what to do, so I have to remind myself that 1.) no matter what happens, it will get done. 2.) try not to repeat yourself. 3.) why did the author write this book? Also, what nugget can I retrieve from it to make THIS book unique? What makes THIS book different from another? I try to not do the same thing again.

Adam: I would say, judging by what I've seen, you are succeeding in not being repetitious.

Linda: I only show what I want to show on my website.

Adam: [laughs] What is the difference between art school and liberal arts school? What do you see as the advantages or aspects of either one that strike you as relative/important to book design?

Linda: Oh man do I feel strongly about this. I don't want to make generalizations about programs and their students, but I believe that at art school (getting a BFA), you're mostly being trained to think visually and make things. Perhaps only a minor part of your coursework is in the liberal arts. Getting a liberal arts degree means you're being trained to read and think in a wide variety of disciplines, which eventually becomes an advantage for book covers — if you're the type of person who enjoys designing for a wide range of subject matter (especially non-fiction).

Linda's cover for the recently published book Jazz Palace

I'm not saying that BFA grads are poor readers (you can be a good reader regardless of your training), but I think in terms of knowledge, having a liberal arts background gives you more breadth and understanding of the wider world outside graphic design, as well as a set of critical tools. And you're not afraid to tackle subject matters beyond your comfort zone.

Adam: It's a great point: that being an informed and thoughtful reader is as important or more important than being a strictly visual designer.

Linda: To a large extent. Definitely when tackling more complex books. A thoughtful reader is better able to parse through the book's contents and make thoughtful connections. But sometimes this can be a disadvantage for an inexperienced designer. You might get so stuck in the complexities and details that it becomes hard to distill everything. And a cover should be simple.

Adam: You mentioned that you and Peter are the only degree holders at your firm that come from outside of an art school...and that in some ways, this places you both somewhat outside of the design “paradigm.” What were your degrees in? What are the drawbacks of being outside? What are the advantages?

Linda: I did art and psychology, but my art degree is nothing like what you might receive at an actual art school. Maybe only one out of the four classes I took was an art class.

Peter did philosophy at Columbia and then music at Mannes (The New School). He was trained as a pianist.

The drawbacks are feeling like you're a latecomer. After my undergraduate degree, I went to Parsons for three semesters for graphic design. Three semesters...compared to eight! So you're already older, have had less training, and are in a sea of all these young, fresh design graduates who know how to design better. So it's a little discouraging at first. I think, in the long run, I don't regret it at all.

Adam: Maybe they are better executors, like you said earlier. But...you can train to be an executor.

Linda: Yeah exactly, it's just practice.

Adam: It's a little harder, in some ways, to train for holistic thinking or to train in time or life experience.

Linda: Yeah, the critical period usually occurs during college.

Adam: I just love that you and Peter are doing so well, though. I really am a strong believer in the “complete human creator” — meaning that a well-rounded person who is motivated is more interesting than a well-honed tool.

Adam: When you are at a bookstore what makes you pick up a book? What images or things make you take that first step of "individual recognition" from thousands?

Oliver Munday's design for The Silent History

Linda: Barthes talked about "punctum" — that piercing feeling you get from viewing an image. It jumps out. A lot of the time, I gravitate towards covers that are either simple and clever, or just visually fresh (usually this involves a lot of negative space). An example is Oliver Munday's (he works here) The Silent History.

If everything around the book is busy, the simplest book will jump out first. Simplicity and elegance, saying more with less, and finding a clever solution. Of course this is not an appropriate solution or approach for all books.

Adam: How about considerations of the "new" kinds of display or the new book stores i.e. web based book selling. Does any thought go into that?

Linda: eBooks

Adam: "How will this look thumbnail-size?"

Linda: Yes — generally the simpler and more iconic the cover, the better. Big, readable type. Maybe one defining graphic.

I think book covers will gravitate towards being more iconic and definitely brighter.

Adam: In regards to your thinking and aesthetics, are there any cover/book designs that were shocking for you...as in near perfection?

Linda: Shockingly perfect?

Adam: For instance, Catch 22. It is still so iconic and effective.

Linda: Oh man, there are so many good ones. I think something that's all-type like the original In Cold Blood is a good contender and Valley of the Dolls. I'm a sucker for that fat didone type.

Adam: This one?

Linda: Yeah, Evan Gaffney did that one. There's a nice feature here: http://eyeondesign.aiga.org/design-history-101-valley-of-the-dolls-book-cover-designer-on-how-he-updated-the-cult-classic/

I'm attracted to books that are predominantly type. Unfortunately we aren't able to get away with that most of the time.

Adam: Can you pick some books of yours that you like and describe why you like them? Why do they illustrate certain things you've mentioned above?

Linda: The Book of Heaven by Patricia Storace:

This was probably the first jacket I did that I actually liked. The subject matter — a re-imagining of heaven from women’s points of view with constellations concealing other heavens — lends itself to a more inventive cover. Instead of trying to simplify (which is normally the case), the complexity of the geode is what makes the cover interesting. I like the depth created by the black universe behind those triangular panels.

The Seventh Day by Yu Hua

I like how the single meandering stroke creates a strong sense of atmosphere and perspective, and I'm a sucker for calligraphic typefaces.

I Am China by Xiaolu Guo

I enjoyed delving into the visual language of punk and constructing everything by hand. There is a rawness, tension, and immediacy that cannot be created digitally.

Dust by Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor

There is nothing spectacular about this cover save that it was my first time using Photoshop to construct the art (which I'd been avoiding for far too long), so it marks a personal (albeit small) milestone. The soothing colour palette is also pleasing.

Facing the Wave by Gretel Ehrlich

This probably most embodies what I like about good non-fiction covers. It is simple, elegant, and visceral. The symbol of Japan drowning or bleeding (however you want to read it) is a perfect visual metaphor for this book.

Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill

The process behind this cover was pretty labourious. I think it captures the unique, poetic, fragmented style of writing, as well as visualizing the many cosmic references in the book.

Adam: Am I correct in assuming a lot of your text is done by your hand?

Linda: No, I use type most of the time!

Adam: Well shit, I’m not as sharp as I wished! An Enlarged Heart? The Liar’s Wife? My Age of Anxiety?

Linda: That's handlettering yes, but that's a minority!

Adam: Akin to the pressures of high school...I imagine finding the right font in your business is difficult. What I mean is, you feel pressured by your designer colleagues to pick a "cool" font that's not "overused" but also workable. Afterall, you work with your colleagues and rarely with the general public (who the book is actually for). I imagine your colleagues judge you more directly, for better or for worse.

Linda: That's true. It's hard to not design for other designers. It's what keeps it interesting That's often a measure of what's good (when other designers appreciate it). And, yeah, picking a typeface is fun.

Adam: Right...how many versions of comic sans do you have? That’s the real level marker!

Linda: I have two, including comic sans neue, an updated version of it [laughs]

Adam: You say you are a book cover designer. What about the spine? the back?

Linda: Those are usually afterthoughts for most books!

Adam: Even the spine?

Linda: Most of the time I'm just glad the cover's done, and I won't have to think about it for some time.

Adam: This strikes me as crazy...it's the only thing that gets seen most of the time, no?

Linda: It depends on the design. When we do the mechanical (setting up the copy for the cover on the front, back and spine), that's when we'll design the spine and it will follow the cover.

Adam: Which gets to another question: do you get to choose the size of the author’s name versus the book’s title?

*Note: Not Linda's design

Linda: I’m glad you asked because, for paperback, they will sometimes dictate this! Like, for this book the author's name is most important...the author is the selling point.

Adam: Right, I thought so. "From bestselling author DEAN KOONTZ...The Lair (maybe a title of his, probably not).

Linda: Yes! exactly. Marketing tactics! Sometimes if I set the author and title as the same size, my art director will ask if the author is that important. So, for paperback, it's definitely more strategic; for hardcover, it is more aesthetic, but it ultimately depends on the author, right?

Adam Do you think of the book’s life after the sale? Or what your relationship or your design's relationship with the readers?

Linda: I generally don’t think much about my covers after they’re printed. Usually the time between designing a cover and when the book is finally on sale is anywhere between 8-12 months. That doesn’t mean it’s not nice to stumble into a bookstore and spot your covers. Still, it is a strange feeling. Whether or not I like my design, my heart does a little flutter. It’s like spotting your babies out in the wild — you have intimate knowledge about each of them and you wonder who is going to wander by and be intrigued enough to pick them up, and you imagine the subsequent life they will have together, the reader and the cover. On social media, it's fun to see others posting my book covers for some of the more popular books. The cover becomes the only piece of advertisement.

Adam: How does your environment influence your design or thinking?

Linda: There's the immediate environment of your workplace, and the greater environment of New York City. If I’m surrounded by talented, thoughtful, and hardworking designers who are at the top of their field, I will inevitably absorb some of that positive energy. What I see coming out of the printer every now and then is itself a huge learning experience. The books and authors we get to work on are also considered some of the best in the English language, which doesn’t hurt! It’s very motivating.

In terms of physical workspace, I never thought I’d say this but I actually enjoy having a cubicle and benefiting from even the illusion of privacy. I recall describing my ideal work environment to someone before I got this job: that I would be happy just sitting at a desk, in my own world, solving design problems. That is a pretty accurate description of what I do.

Living in New York is also wonderfully stimulating. In addition to the designated zones for art in museums and galleries, the vernacular designs — from supermarket posters to takeout menus — are a rich source of inspiration that can sometimes work their way into covers. There is a lot to be noticed in the city.

Adam: How does your work as a designer/book designer influence your life? How does it change the way you look at things?

Linda: As a book cover designer I am more understanding of design choices behind the marketing of a certain book. I can see when a final design was more driven by sales, for example. I judge books by their covers because that is my job, but at the same time, I know when to not.

In terms of being a plain designer, I am very sensitive to typography in my environment, particularly the poor kerning and spacing on those horizontal subway ads. I find myself mentally adjusting the type and questioning the successfulness of an ad campaign. I am a more critical looker but have also become more easily amused by mundane street sightings and juxtapositions, for example, the inadvertent arrangement of objects that might resemble a face, or something else surreal.

My boyfriend is also a graphic designer. Living with him for the past three years has probably been the single biggest influence in the way I see things as a designer. We’re trying to live with more intention — making deliberate choices about the way we spend our resources to create the kind of lifestyle we want. This means more than appreciating nice furniture. It’s about how we can generate more richness in life and extract more meaning with everything we do. I’m making it sound more vague and lofty than it is. It’s an ongoing, active process of refining one’s tastes and choices to reflect one’s personal goals. It’s too easy to let life happen to you, and to be pulled into many directions at once and not question what you want. I struggle with this.

Adam: Are there any other questions you want me to ask?

Linda: Are there cases where reading the book does not help with the cover?

Yes. In certain cases, after having read and represented the book to an author's liking, bookstore buyers will ask for a cover that is completely incongruent with the book because they think it will sell (notably women's and summer fiction!). You are left wondering whether they understand the book at all, or how they feel about deliberately misrepresenting the content. I am not saying that selling the book isn't important; I am saying that we should give more credit to readers and not constantly cater to the lowest common denominator.

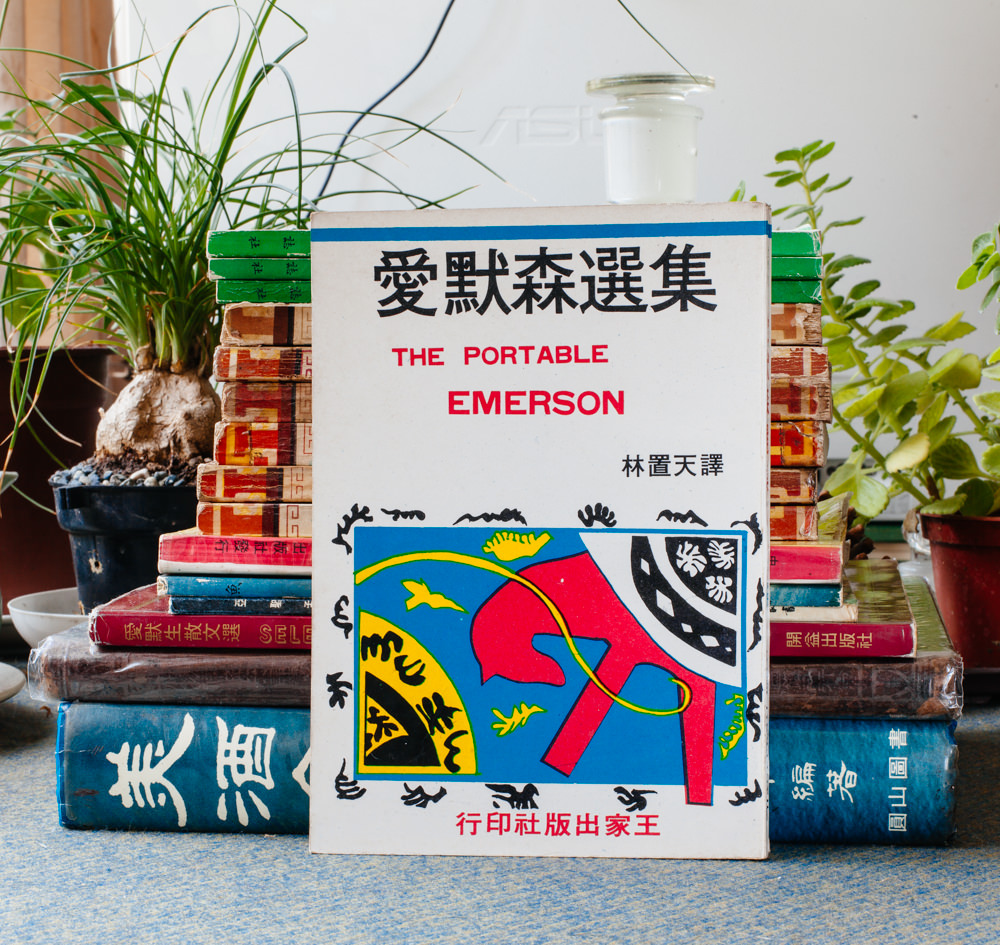

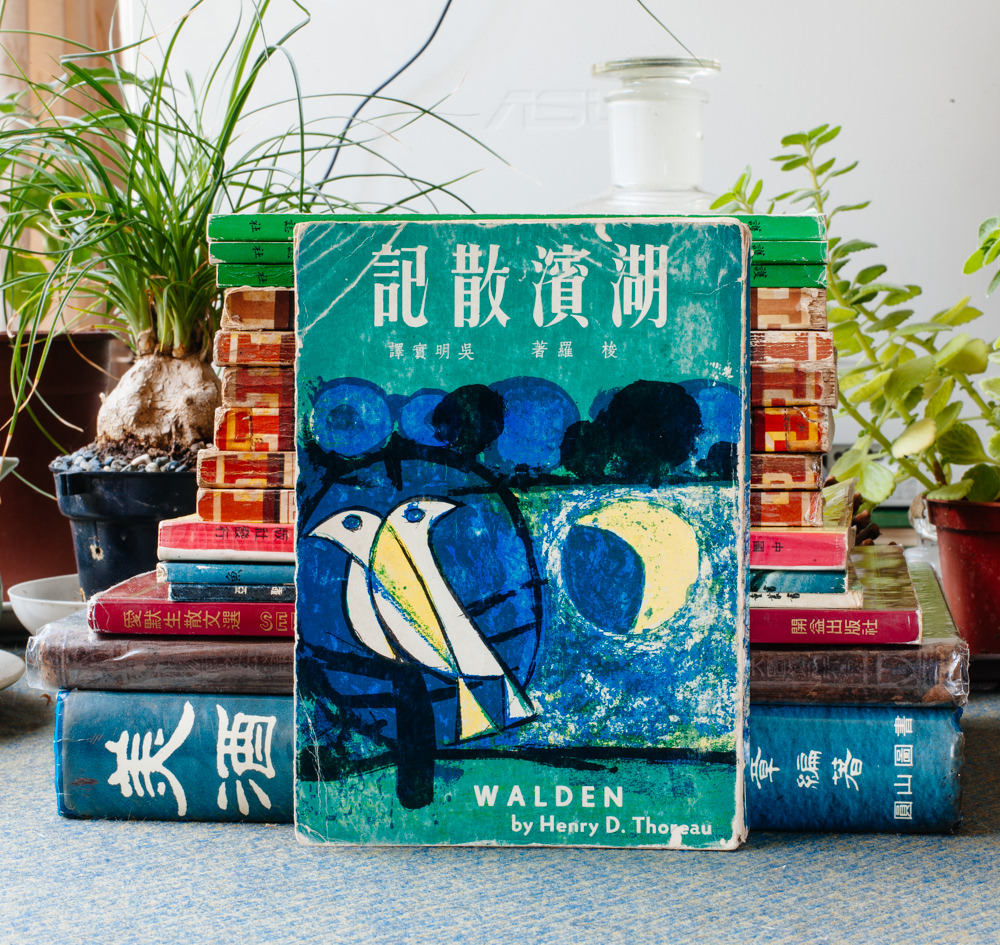

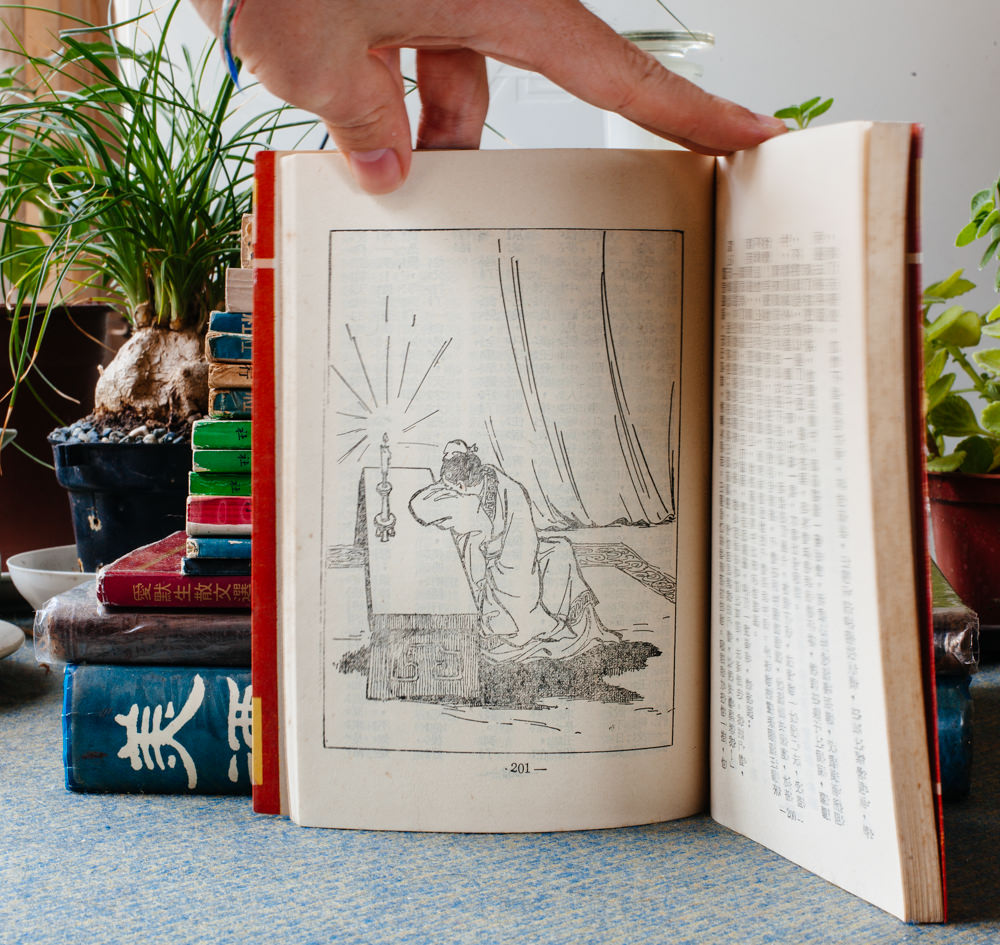

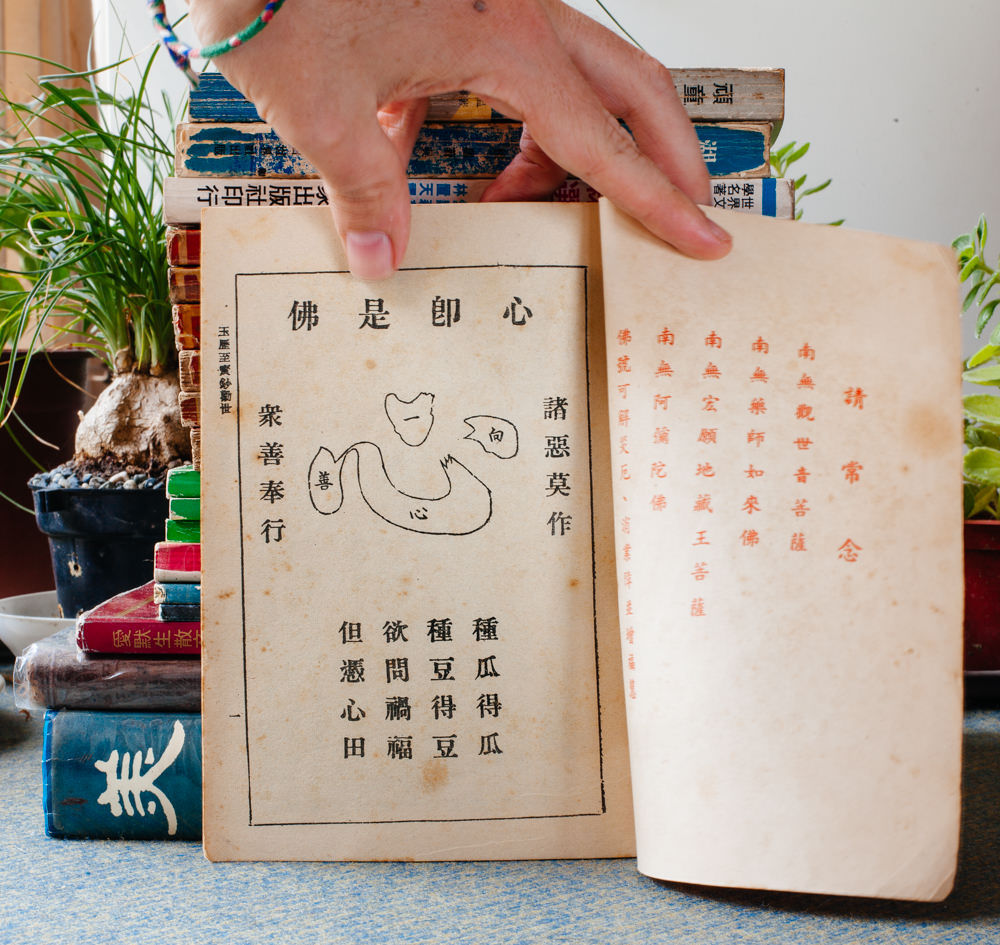

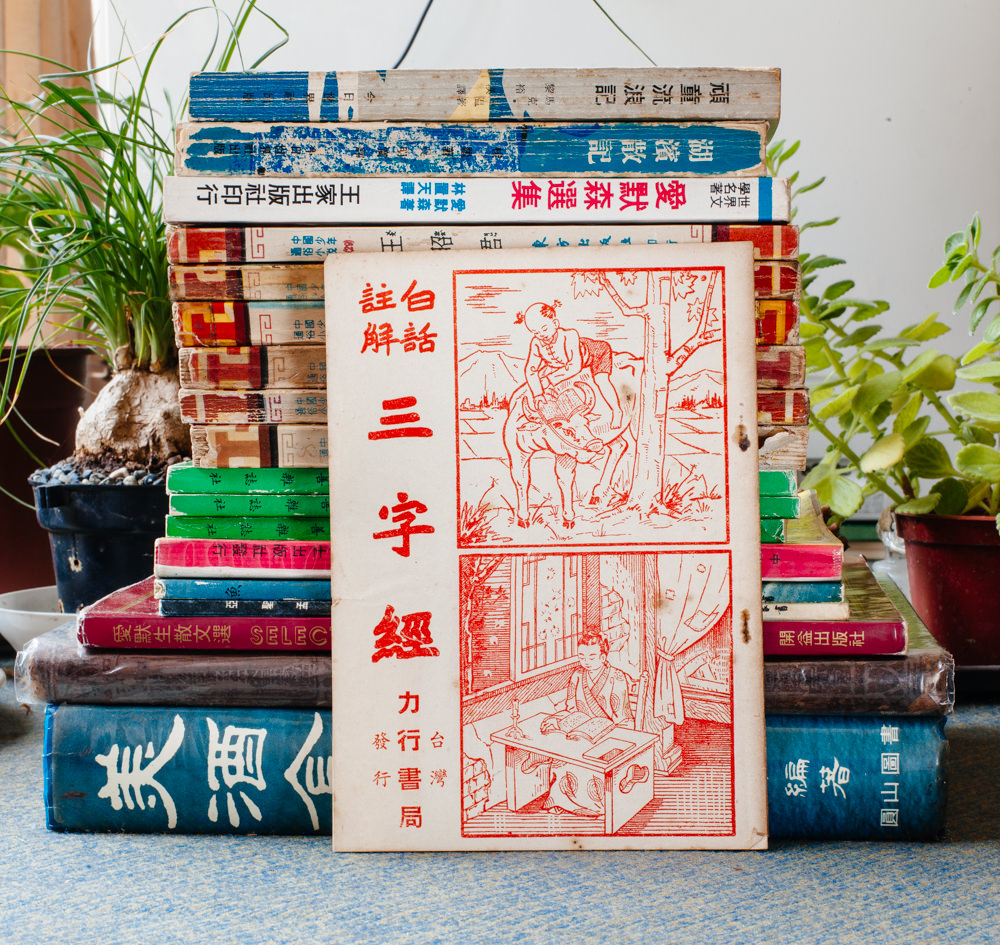

[m] Book shopping in Taiwan

I’ve spent a good amount of time at book stores in the English speaking world. At times, it feels excessive, to the point where I question if the time perusing the books would have been better spent reading them. Reading is the point of books, I believe (this may sound obvious, but it's not and worth mentioning). And yet, books have a meaning of their own outside of the words inside them. They are the covers, the typography, the images, the material...in short, what truly defines a book is the materiality, the design and content combined. Literature may be best visualized now by an e-book...the words reign supreme while it has an almost negligible materiality. The differences of the ‘digital book’ may help us think about the book.

While at the University of Wisconsin, I had the pleasure of working in the Special Collections and Rare Books Department. I was able to see, firsthand, some of the finer specimens of the book. Publications from the Kelmscott Press, Audubon's Elephant Folio, Newton’s manuscripts, alchemy manuscripts, etc... A first edition, first printing can sometimes bring people to spend thousands of dollars for a piece of publishing history. An inscribed copy, especially from a reclusive author, can add additional value to the book...but these things don’t necessarily add additional value to the literature - the substance inside. What about the other elements, though? The paper selection? The weight or smell of the book? The size of the margins? Taken separately, their impact is unnoticed by most people and yet, together, the elements that make these books objects have a major effect on the reader.

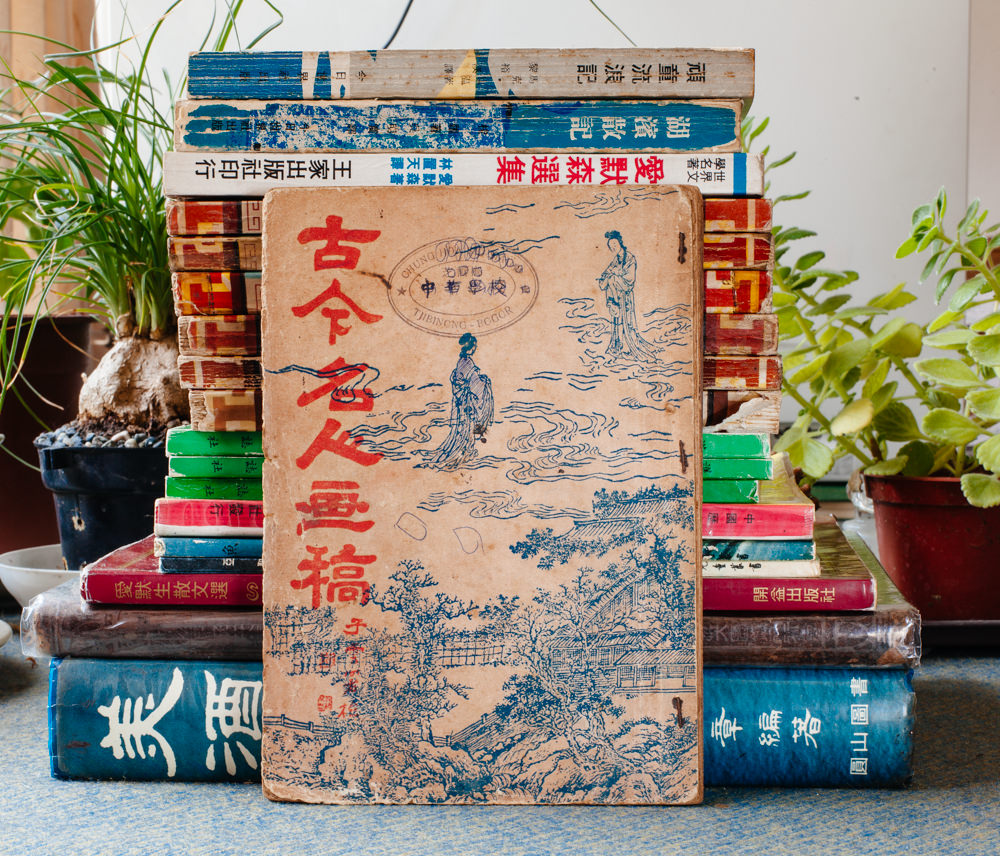

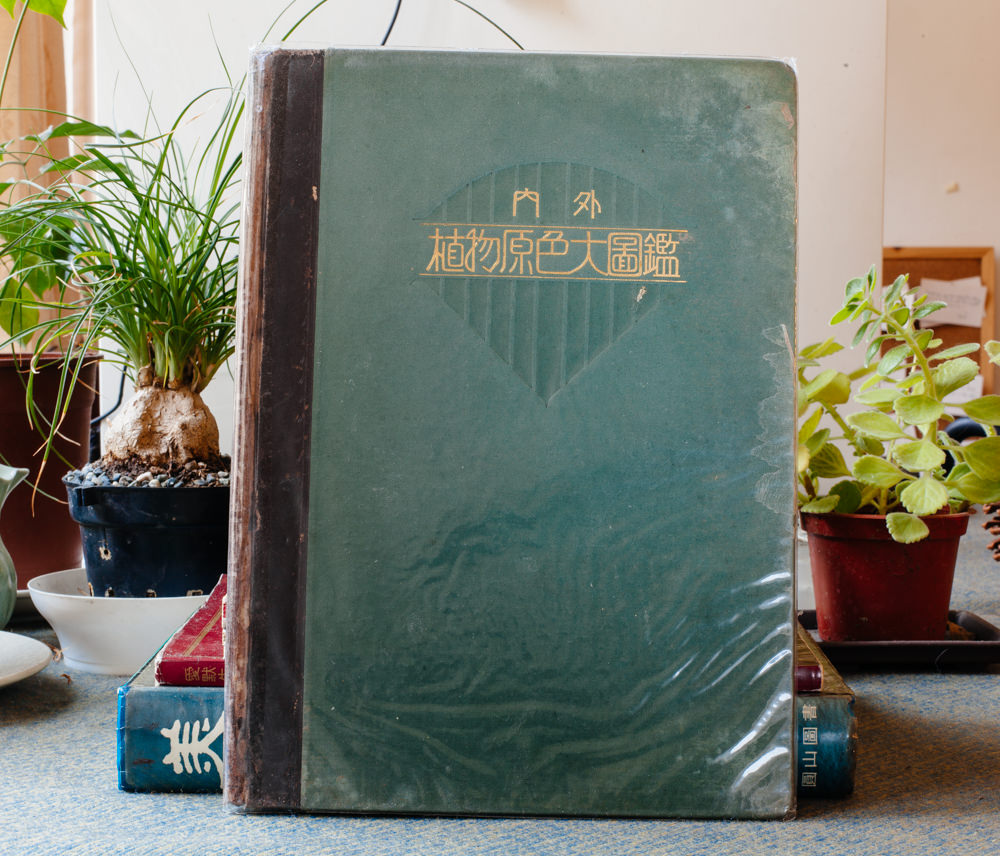

Upon my arrival in Taiwan four years ago, the differentiation was real. There was truly only the physical book since the content (I will say the literature) was all in Chinese. This made the written content as good as non-existent for me. What I saw was the book craft, and the surface imagery of these characters. I bought nothing and I looked rarely. Certainly there were intriguing books and covers, but with the substance lacking, so too did my interest in much perusing or consuming.

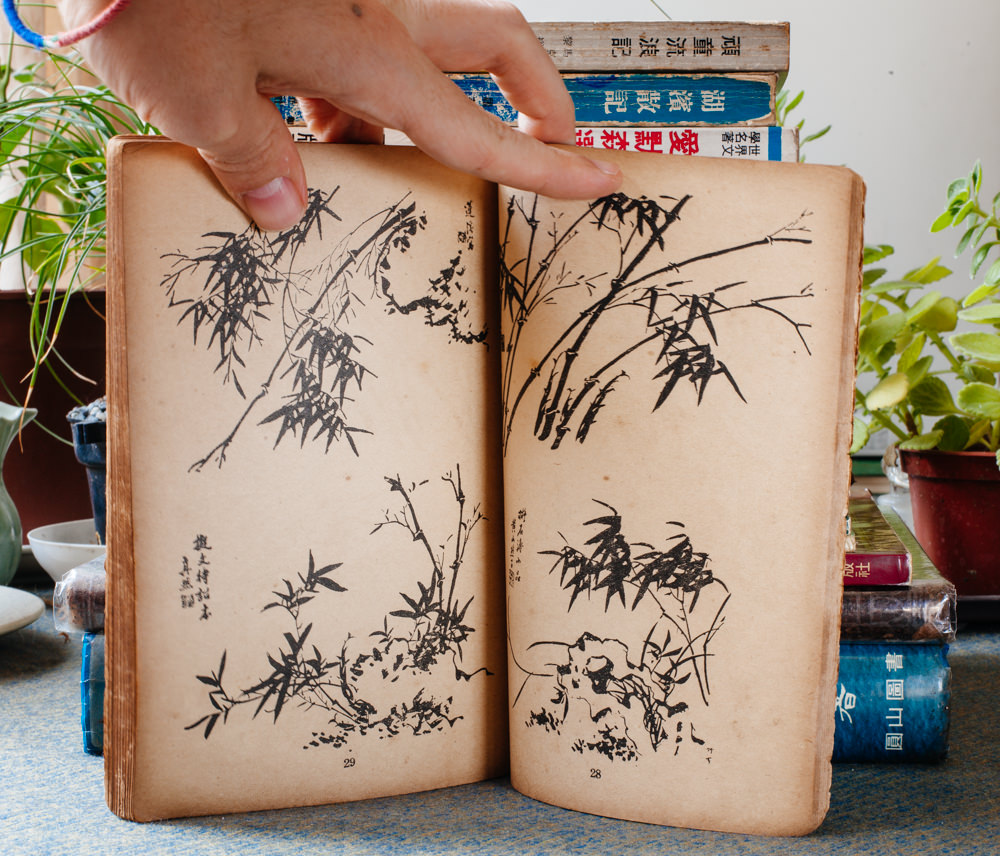

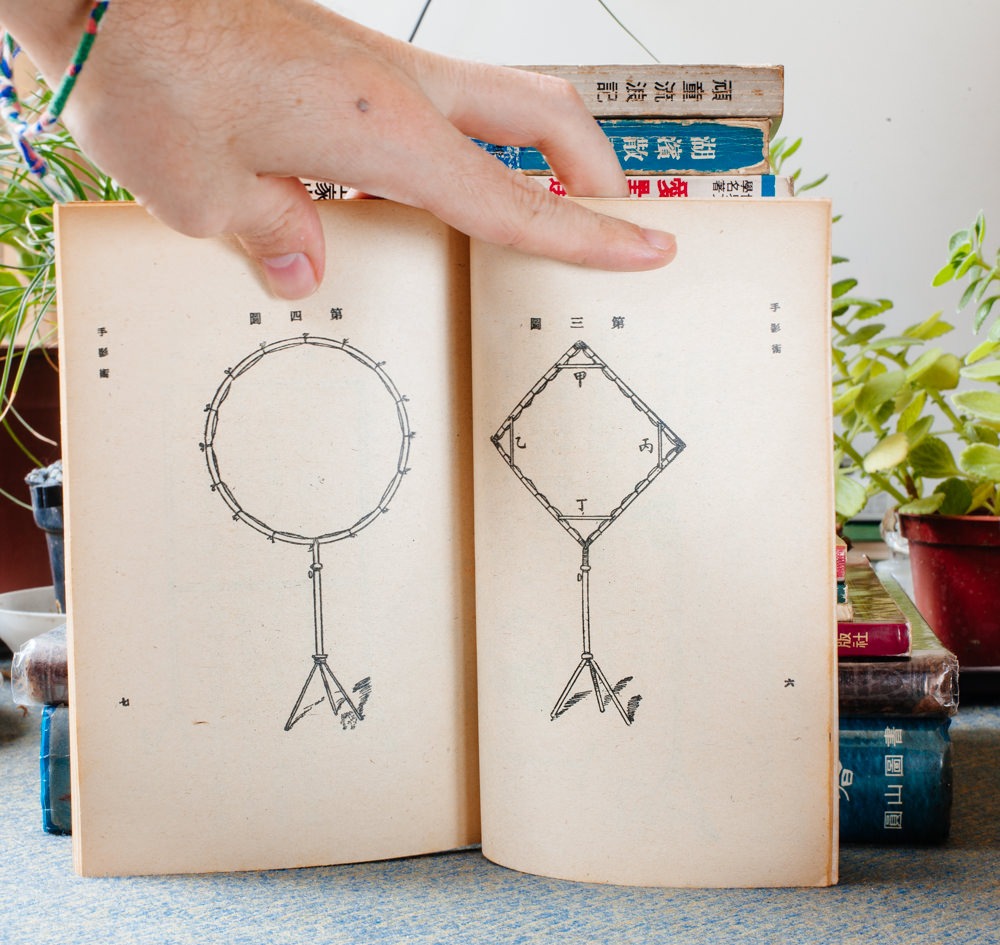

Fast forward to three years later when my Chinese attained a level of understanding that allowed me to grasp the meaning of the title and sometimes even read a large portion of the contents inside. With this change, these beautiful objects transformed into the more substantial book. There is an extreme beauty and effect in the philosophy of the e-book - the writer's words stand on their own in a nearly level playing field. And yet, the materiality of the book and the things that lay outside of literature tend to enrich our experience in a way these new devices do not. Reading is not just about our sense of sight just as listening is not just about our sense of hearing. The other senses, defined or not, are always influencing us. The book - its typography, images, paper, size, literature - is a wonderful sum of its parts.

I wanted this little brief introduction to work as an introduction to these few books I’m sharing with you as well as how my experience with Chinese books helped me think differently about the book. The books that follow are of many different sorts - some I chose for the superficial and direct reason that I found them arresting and attractive. Some I bought for their literary content. As I packed up to move, these few books were among my most valued, so I share them with you. Don't pay too much attention to the section heads - there's lots of overlap and its just my way of making this random selection a little more digestible.

Enjoy.

Relatable and Translatable

The dramatic differences between Chinese and English present an extreme challenge to translators, especially with written translation. Roughly speaking, Chinese characters represent words or ideas and have little in common with the strictly phonetic latin alphabet (although many chinese characters do actually have phonetic elements but the rules vary greatly, to the point where many modern Chinese readers rarely think about them).

So how do you translate an English title into Chinese? Chinese takes a few different routes, the two most common are:

1.) Use the sounds of a character to mimic the sounds of the english word (Sometimes, the characters have a clever meaning along with their similar sound...sometimes there is no meaning at all, as below)

e.g. 湯姆索亞 TangMu SuoYa is Tom Sawyer (This has no usable meaning - if forced to translate, it would be something like ‘soup female tutor search asia’)

2.) Use characters with a similar meaning to represent the title (with no attempt for phonetic similarity

e.g. 聖經 Sheng Jing (‘holy scripture’) is The Bible

With that little intro, here are the titles for the first set of books pictured above:

The Portable Emerson: The translator's transliteration of Emerson's name is informed and phonetically similar: '愛默森' (the pronunciation is 'ai' 'mo' 'sen' - say those fast and you will understand why). The characters mean 'love,' 'silent', and 'forest.'

Walden by Henry David Thoreau: Walden is translated as Essays from the Lakeside with no phonetic similarities. And Thoreau? 亨利·大衛·梭羅 (Hēnglì·dà wèi·suō luó) - a purely phonetic representation.

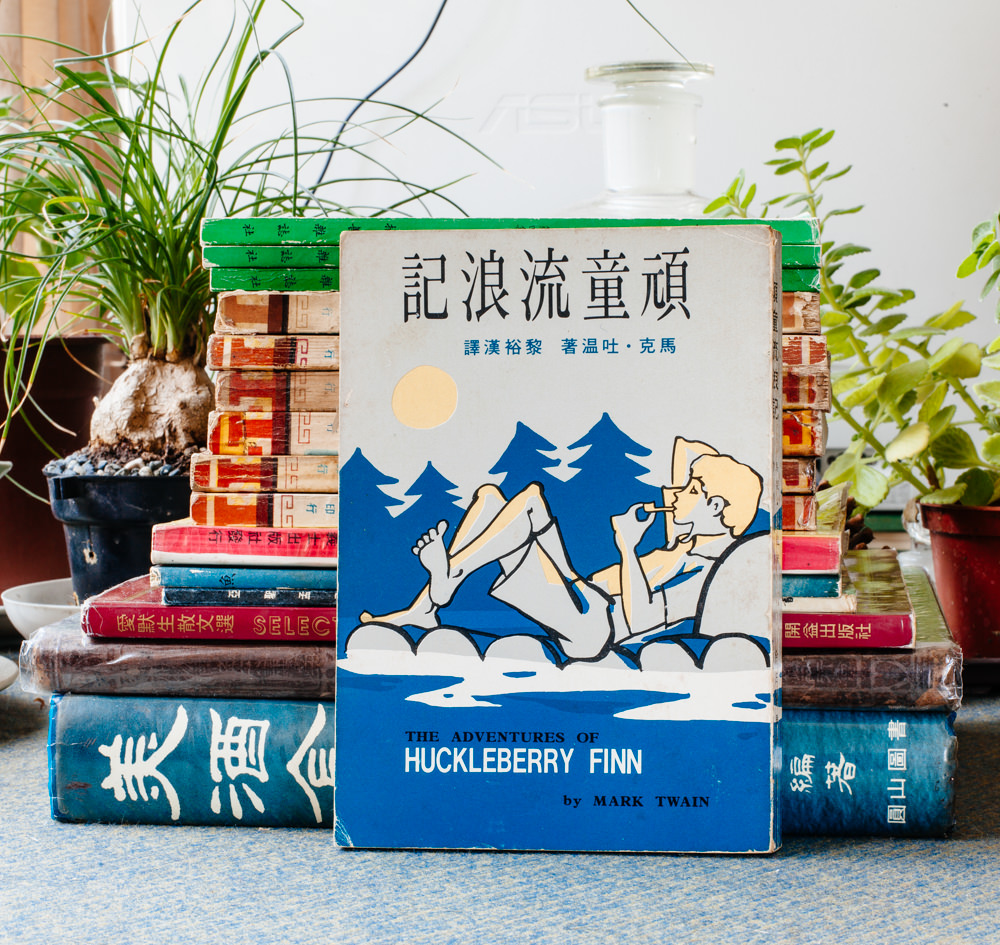

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain translated as The Wayward Wanderings of a Mischevious Child

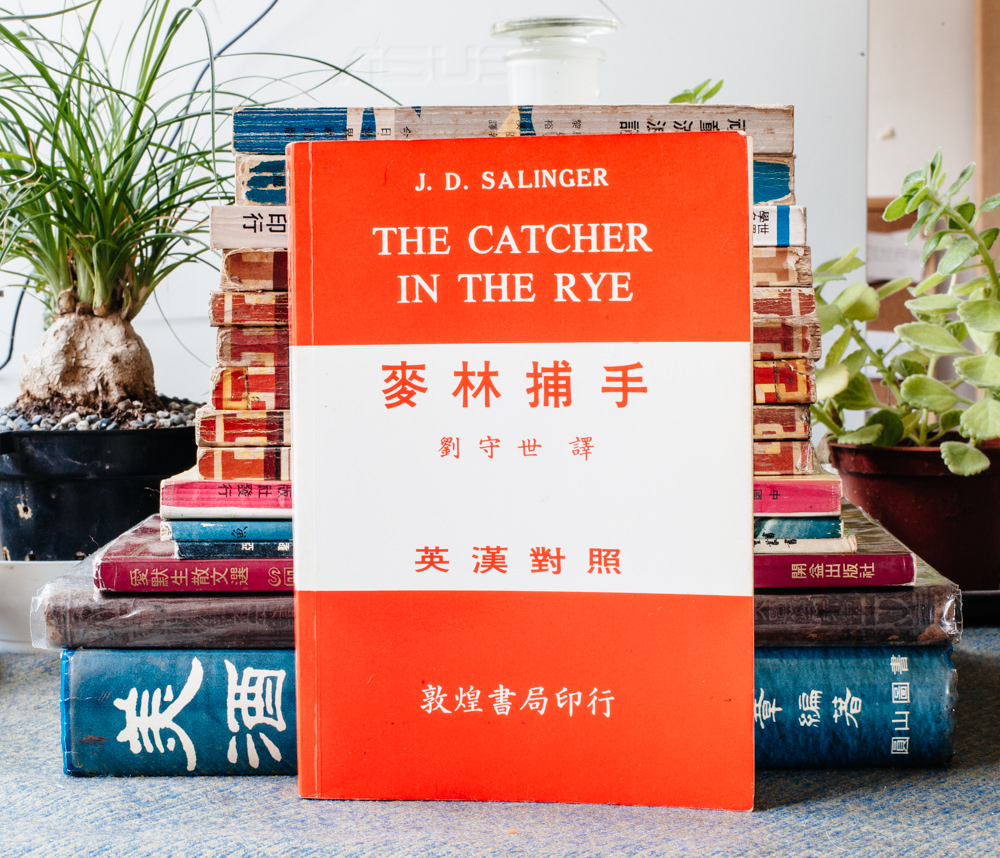

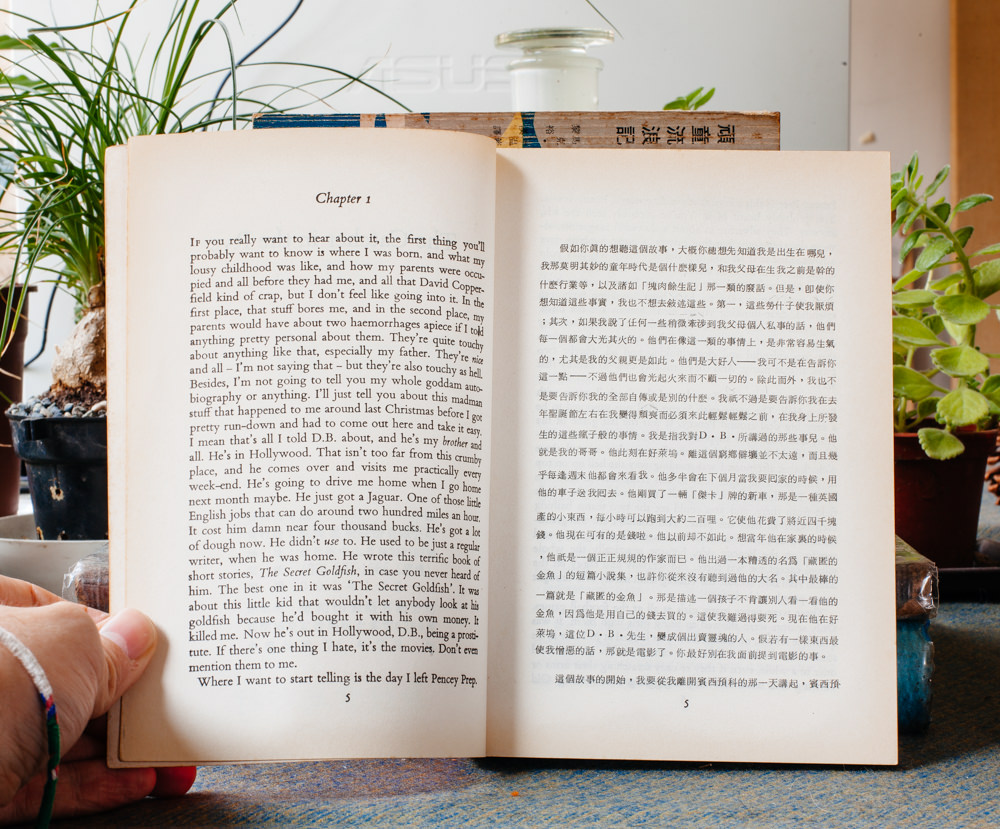

The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger is Catcher in the Wheat Field (here's a newer and less subtle variation on the cover that I saw at the bookstore)

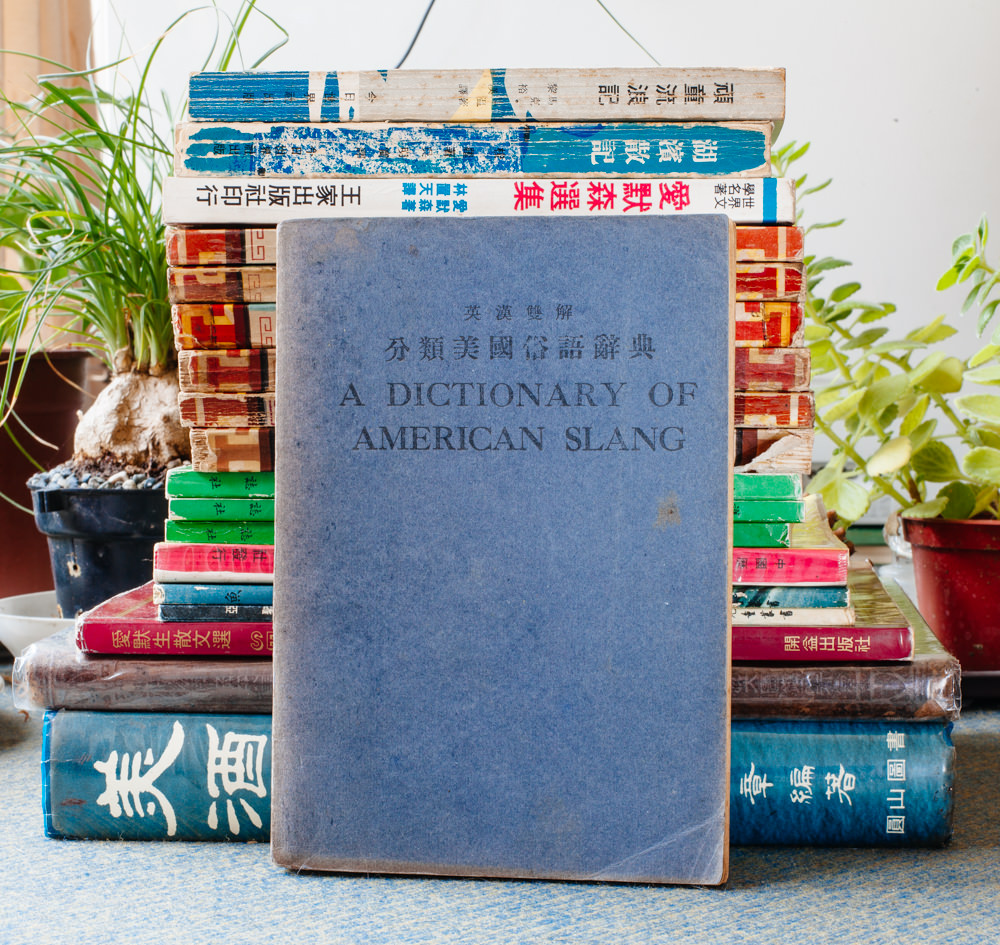

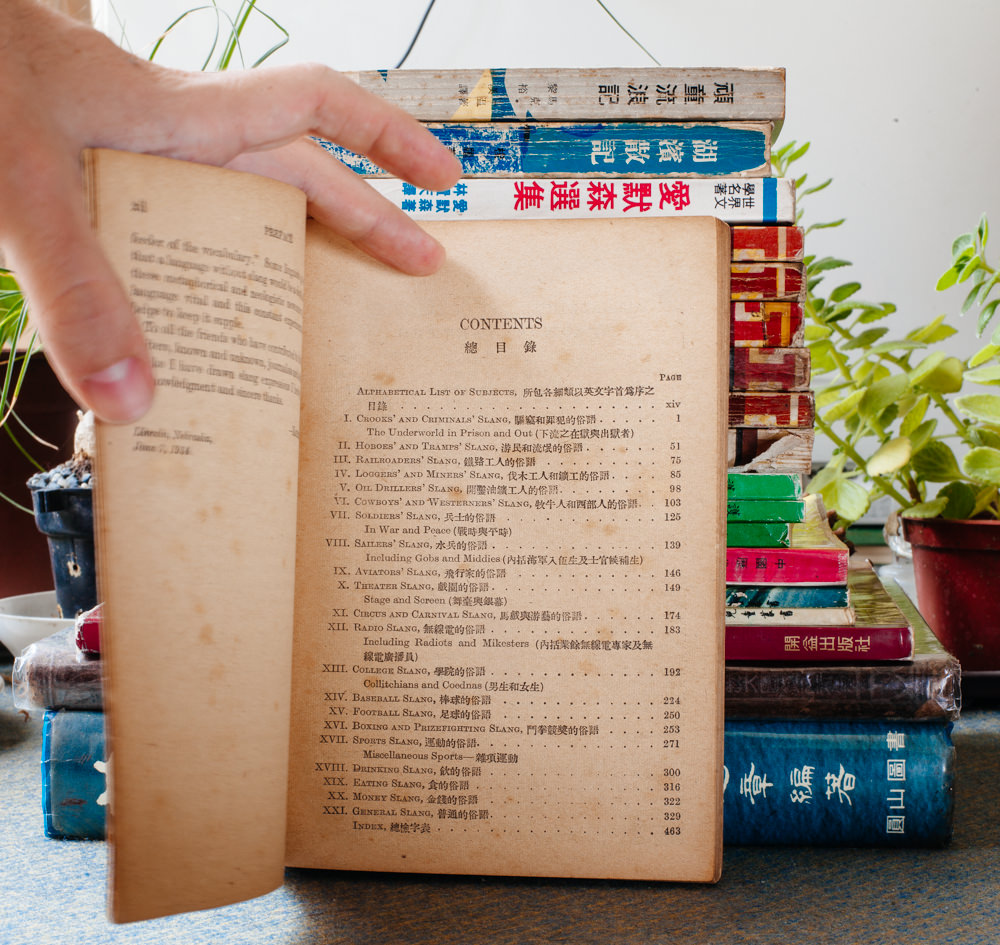

A Dictionary of American Slang by various authors

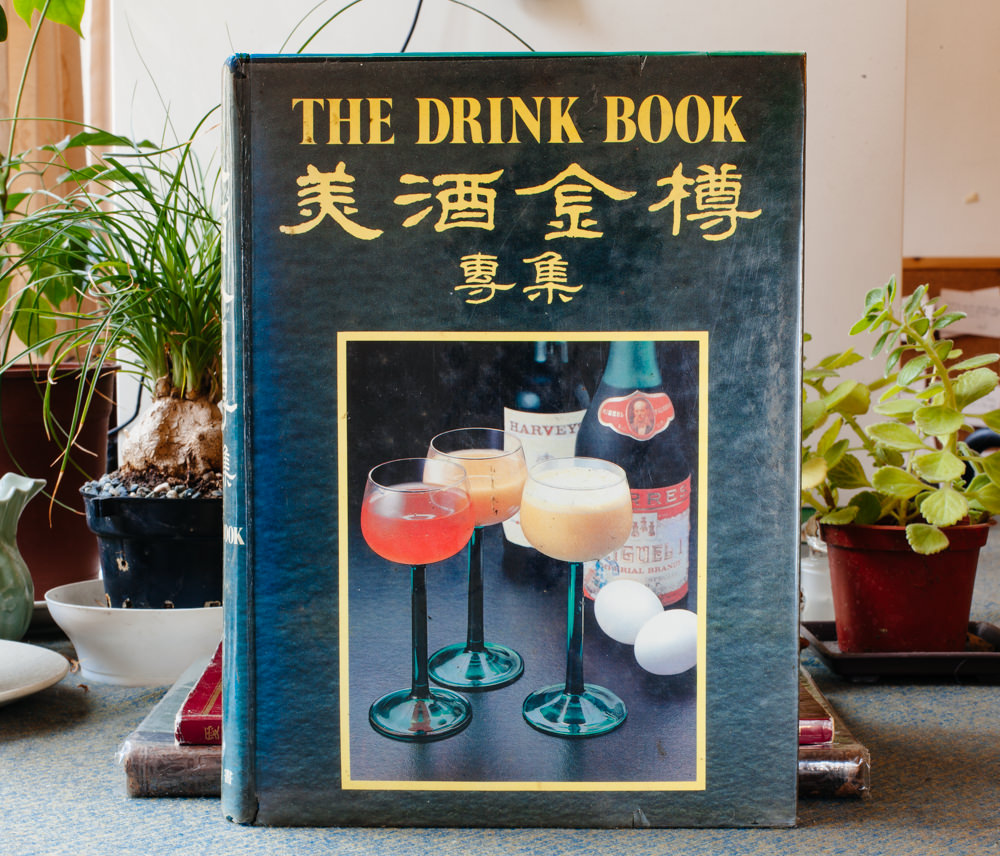

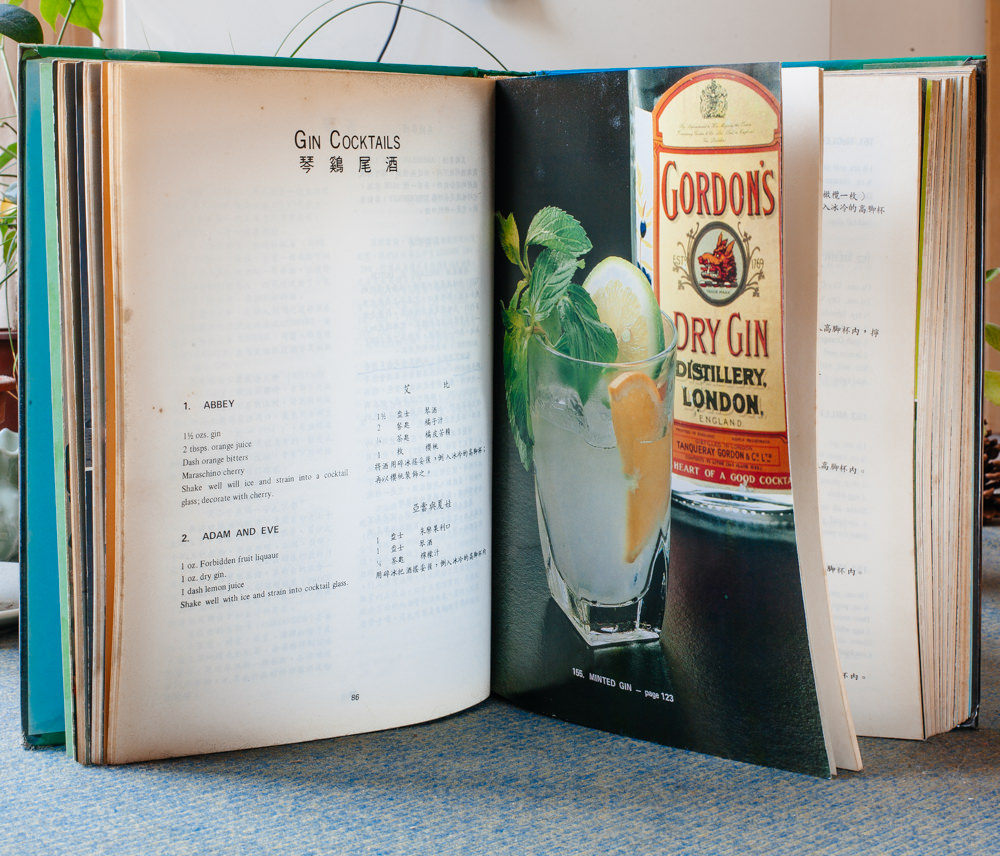

The Drink Book by various authors

Beauty

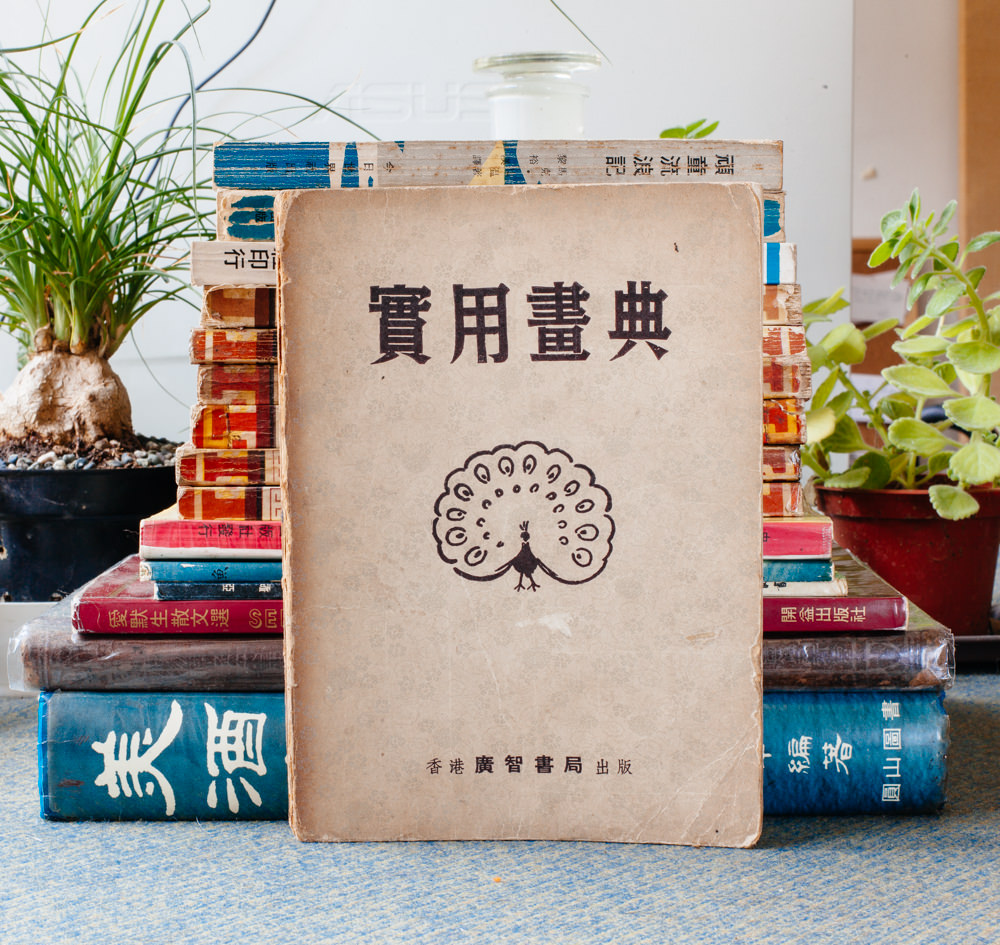

Practical Picture Dictionary

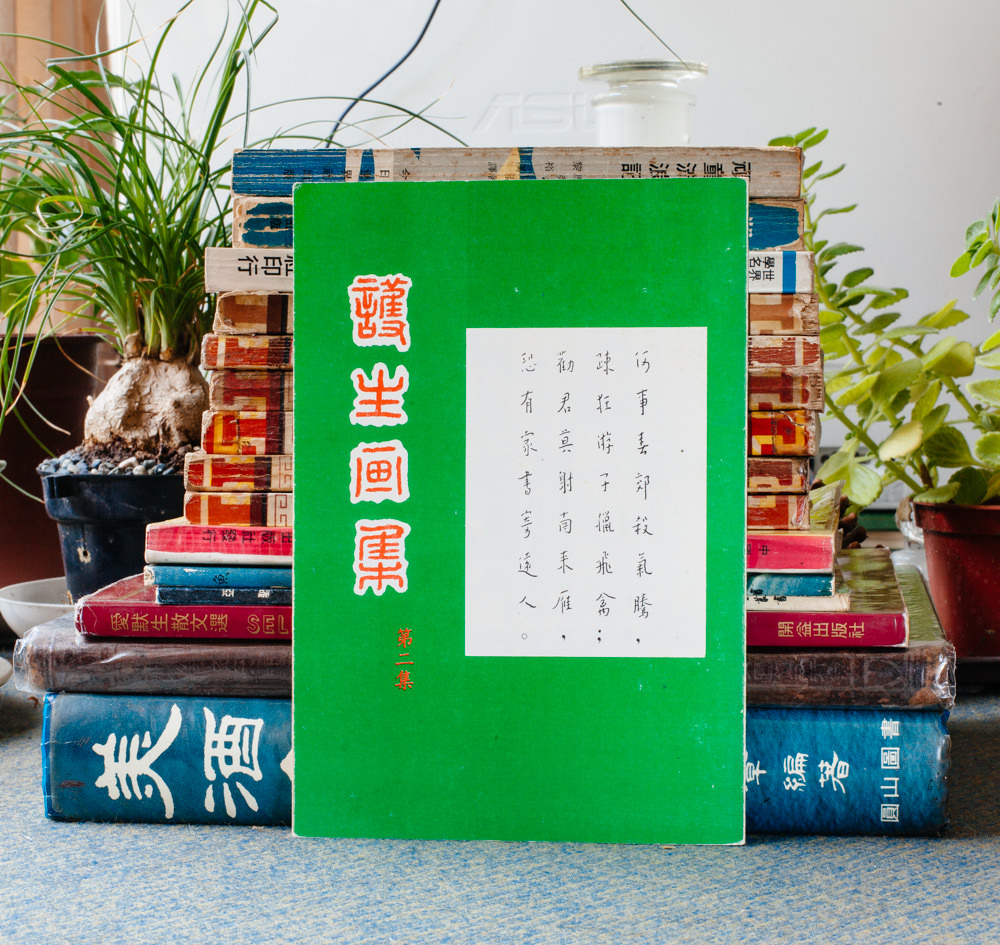

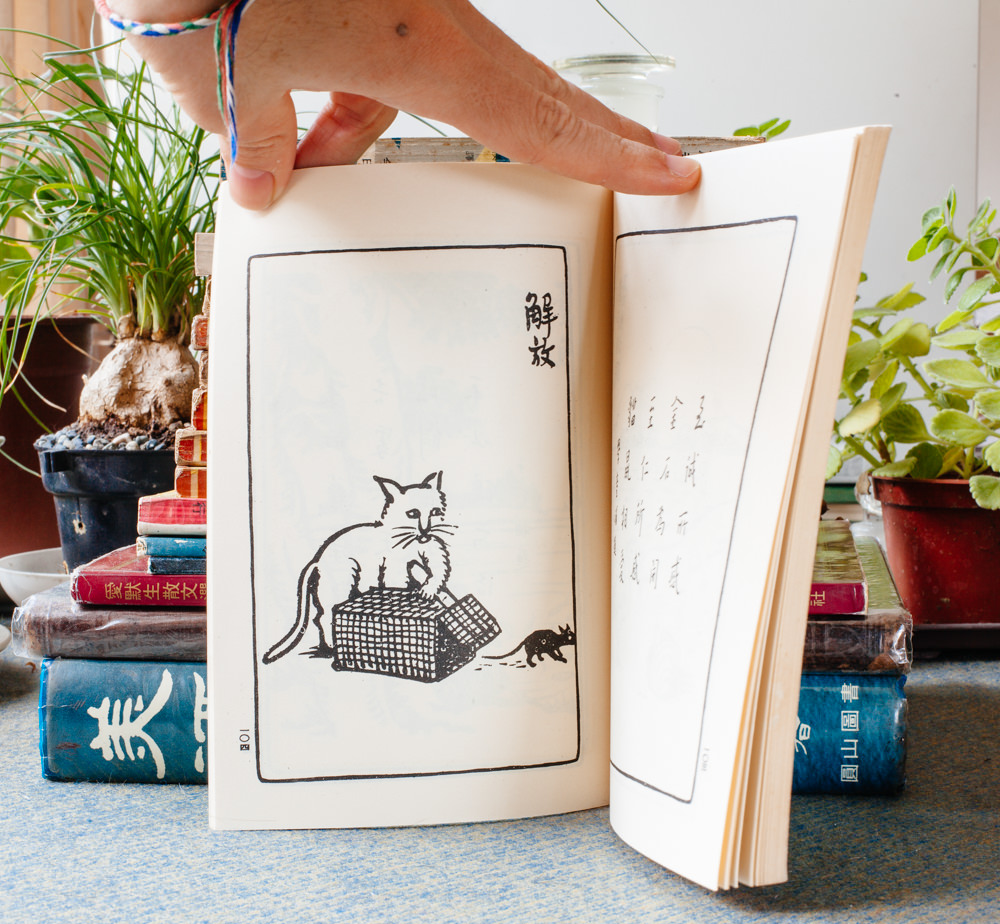

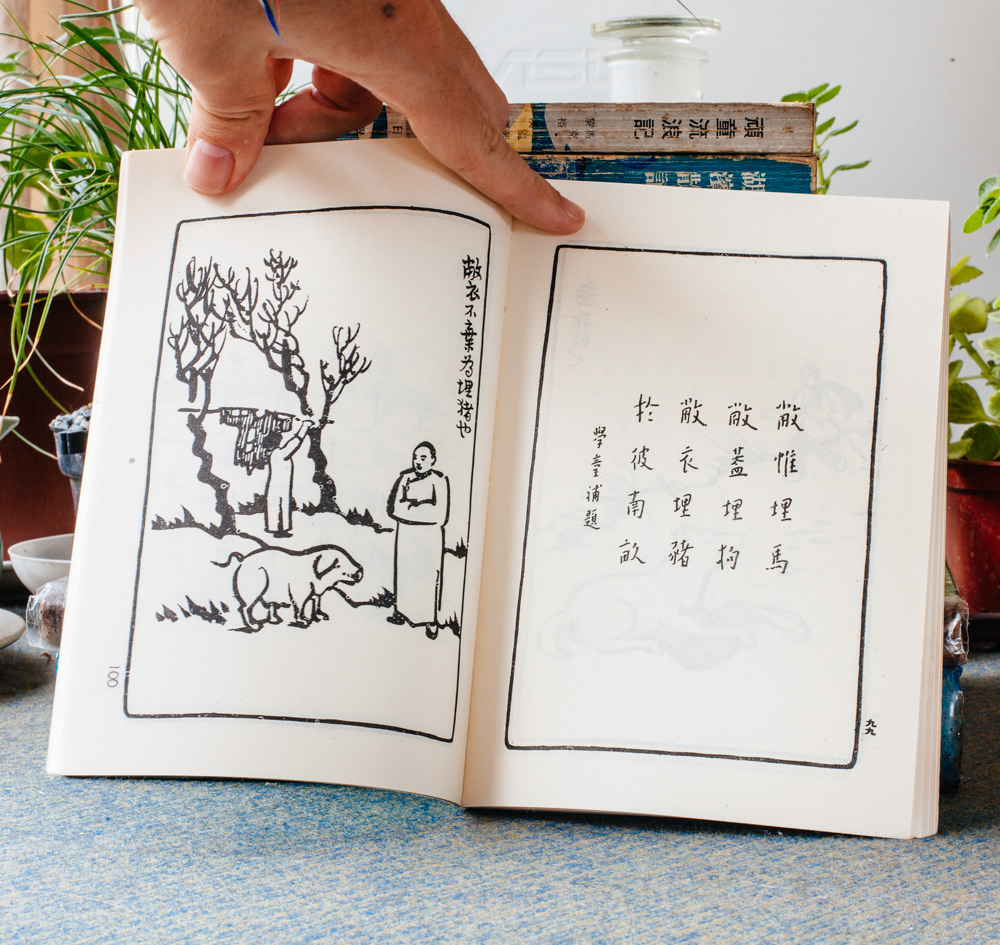

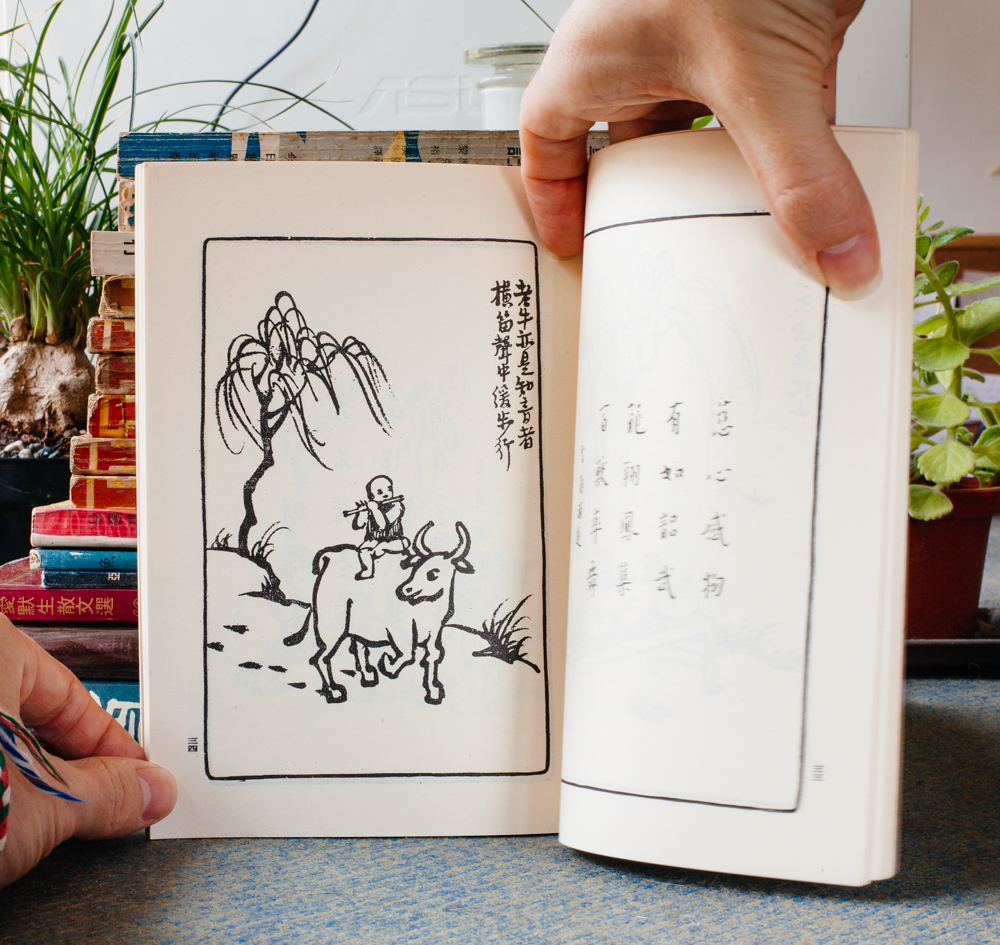

Paintings on the Preservation of Life (Vol. II) by Feng Zikai (I will write more about him, one of my favorite 20th Century Chinese writers/artists, at a later date.)

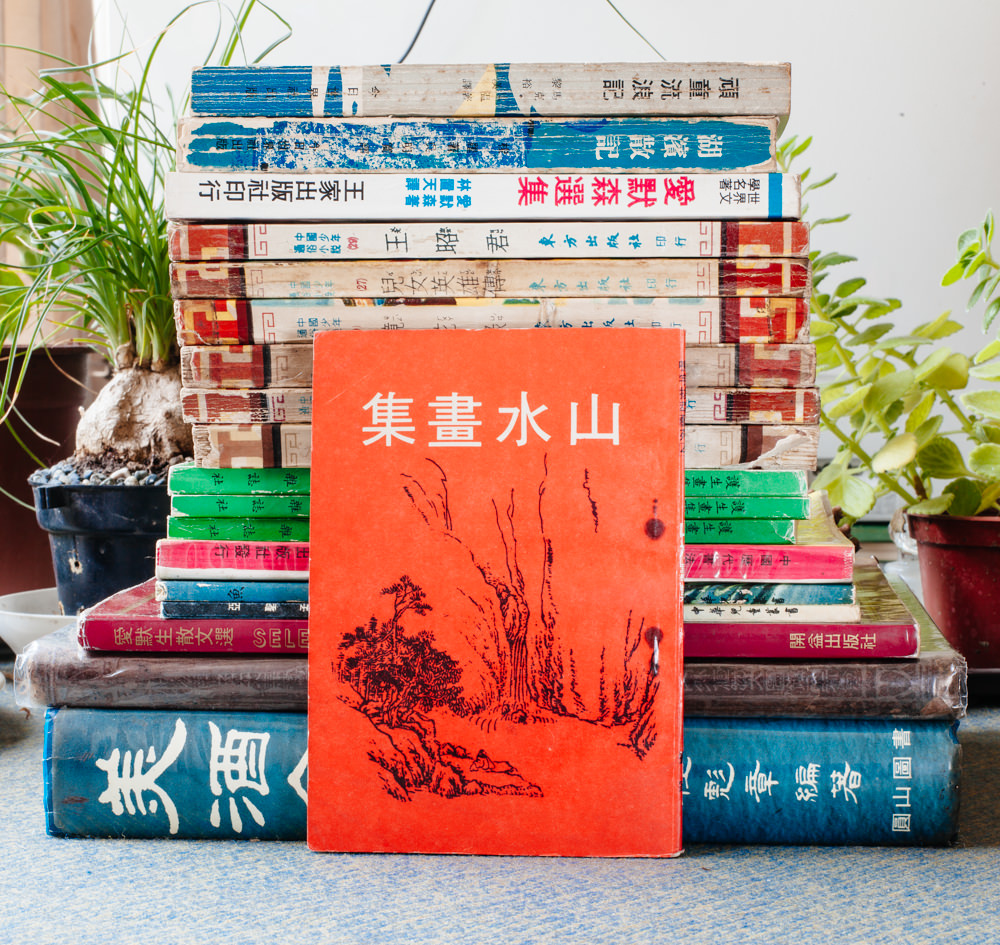

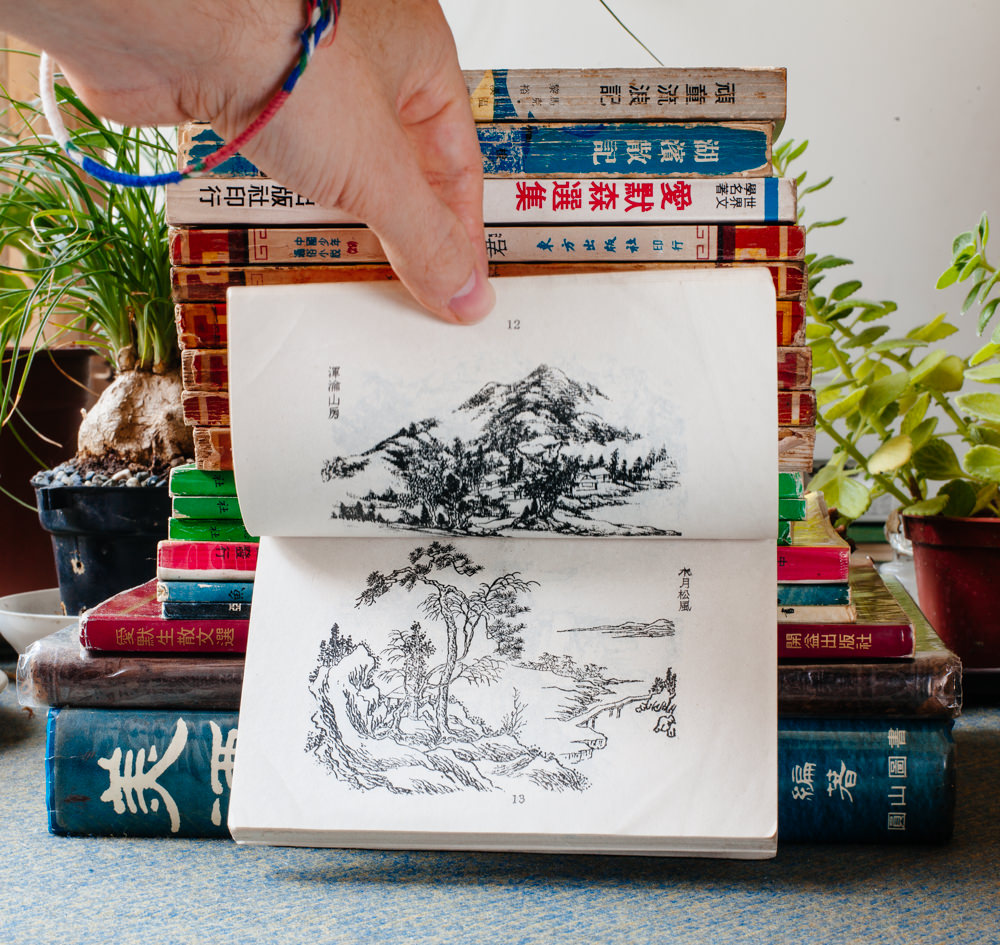

Collection of Landscape Paintings

Manuscripts of Classic and Modern Artists

- Original Color Picture Catalog of Plants

The Strange and Fun

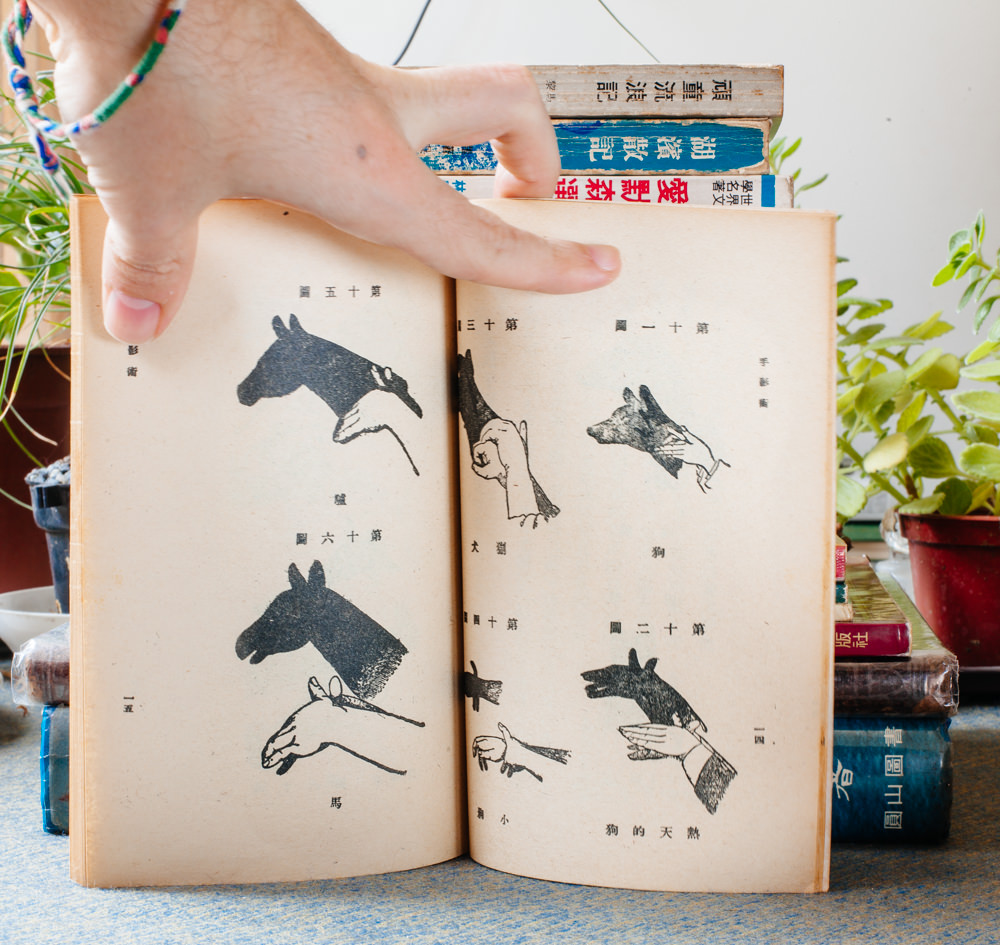

The Art of Shadow Puppetry

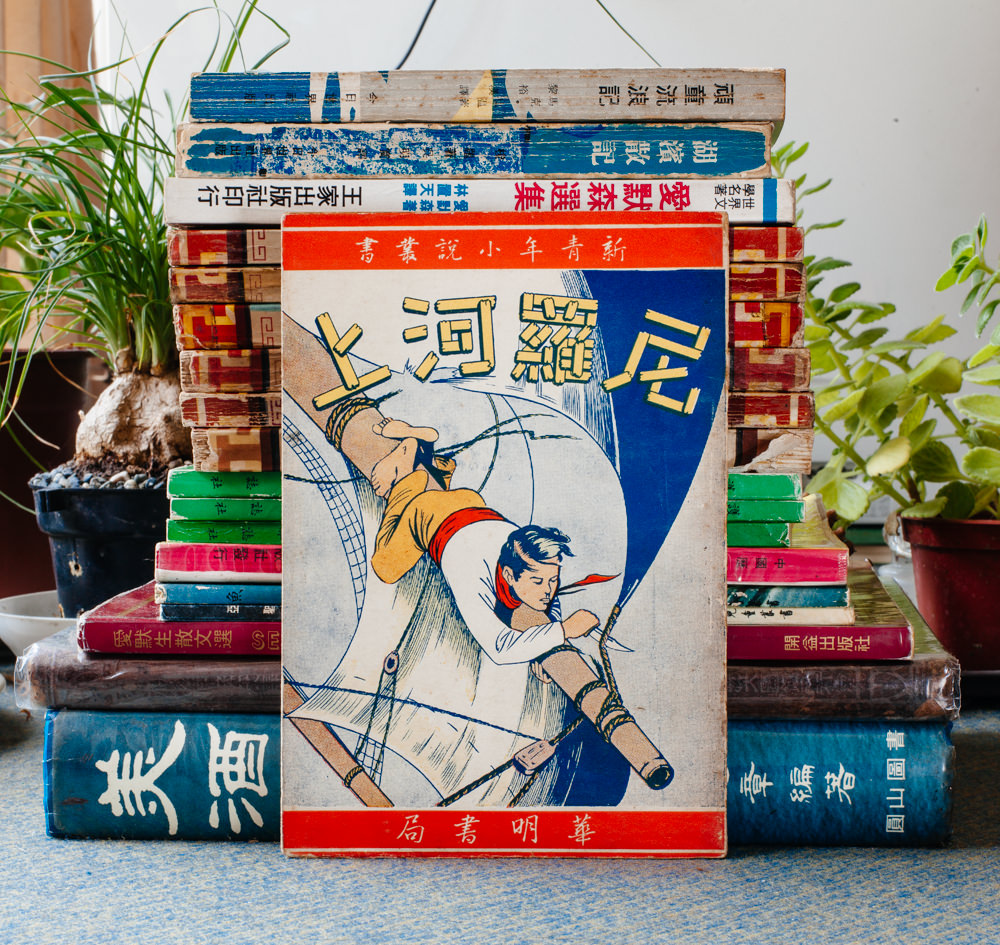

On the Nile River

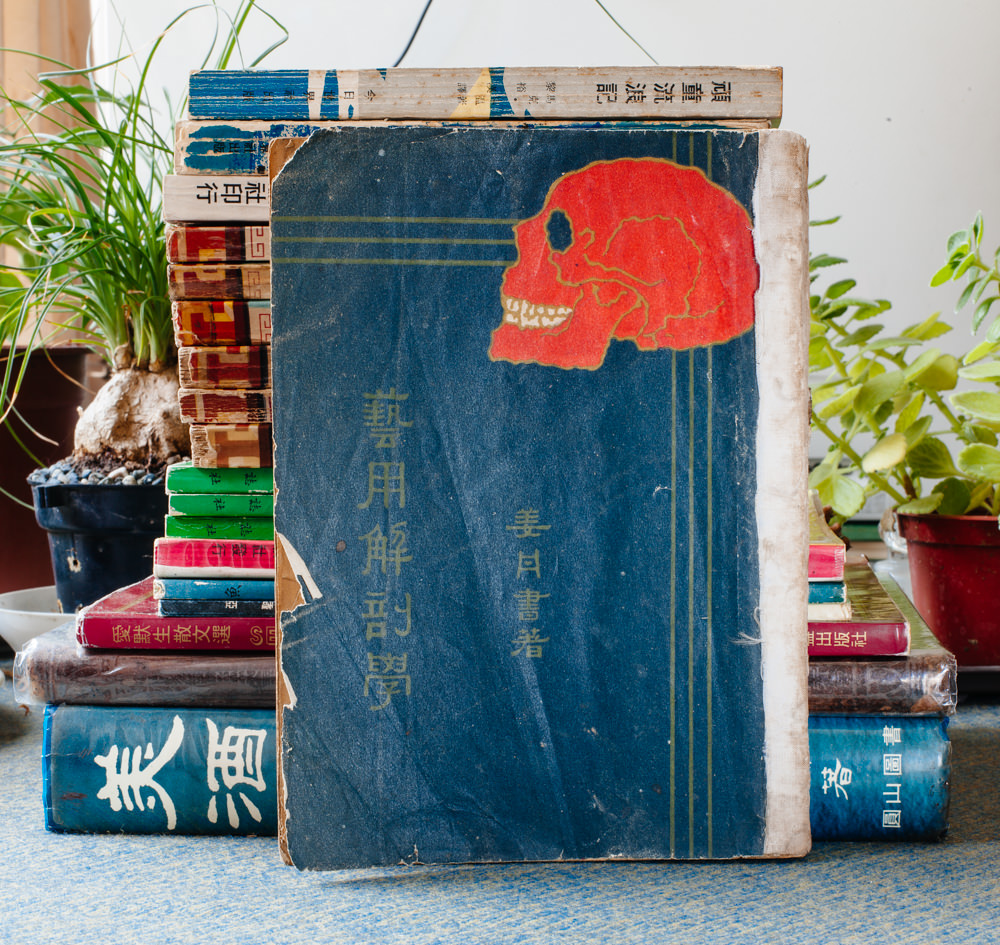

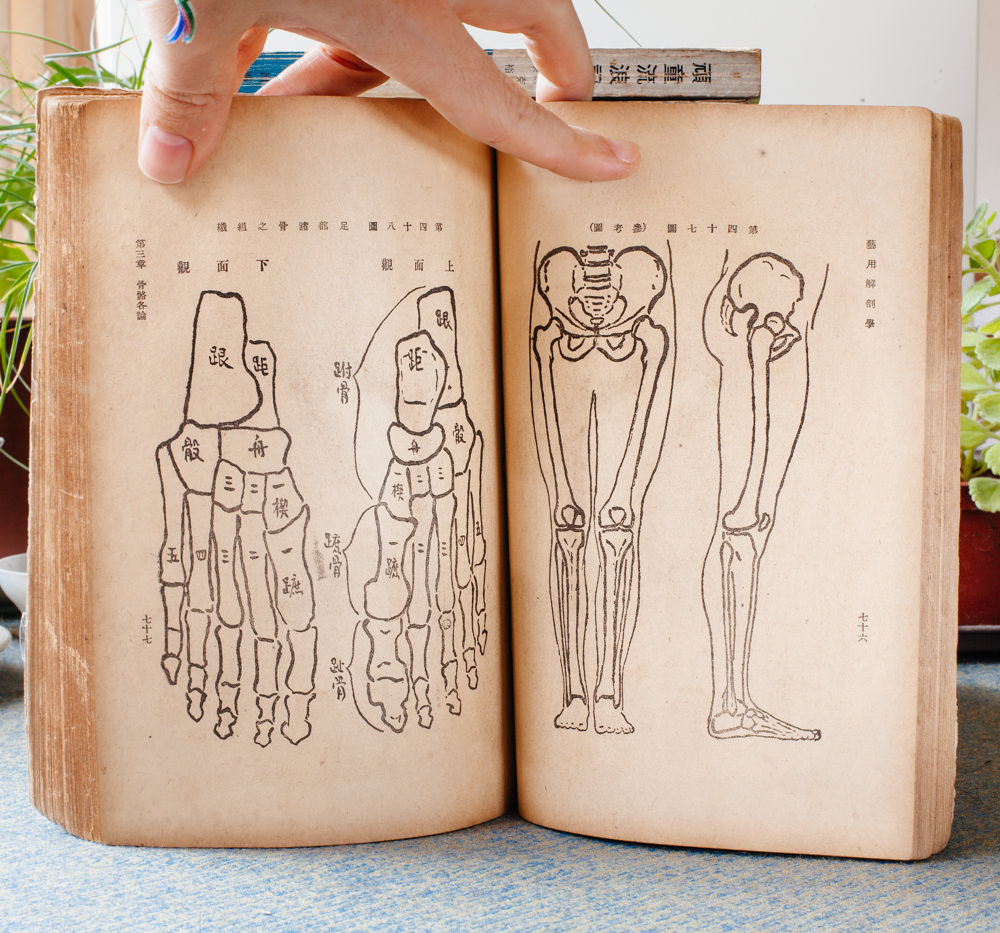

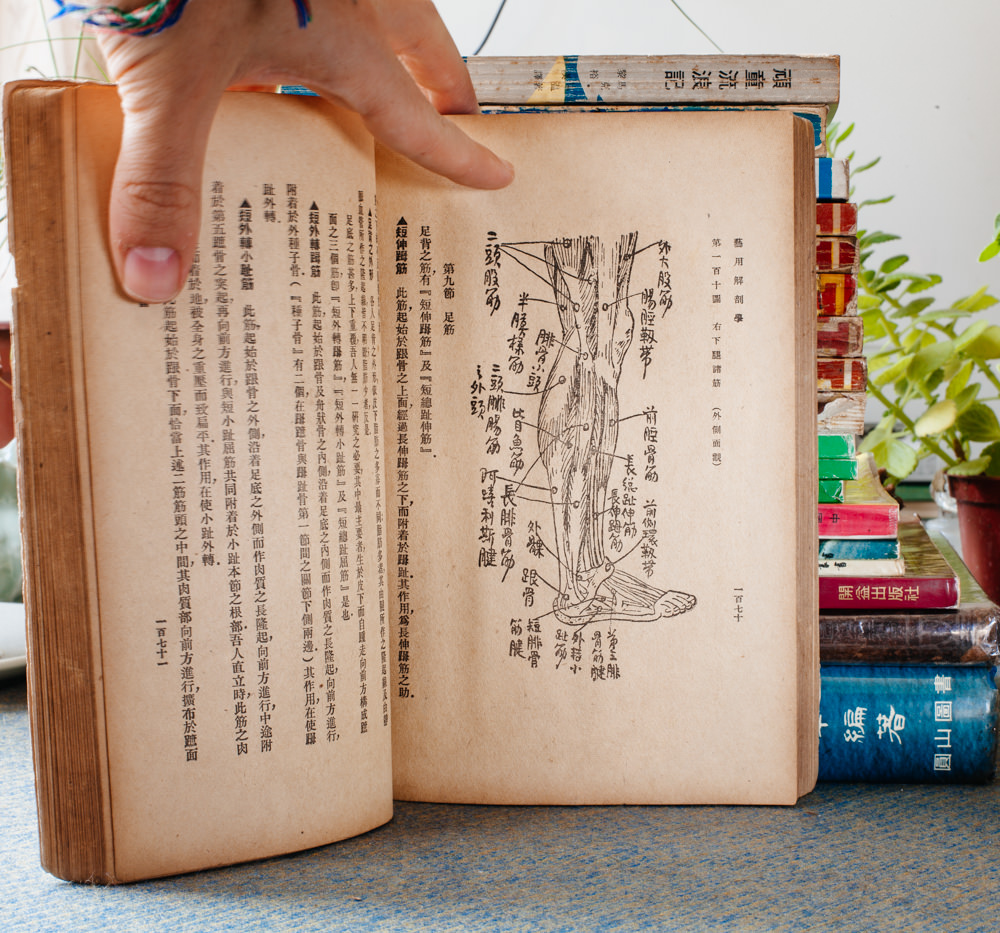

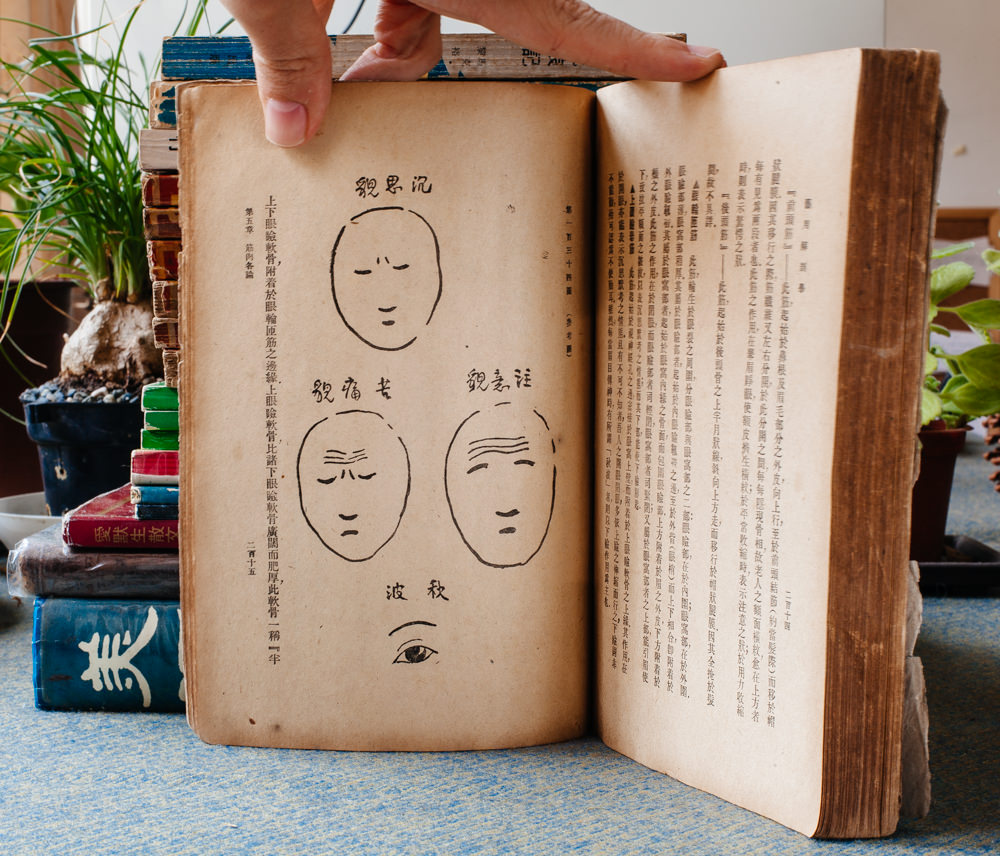

Anatomy for Artistic Purposes

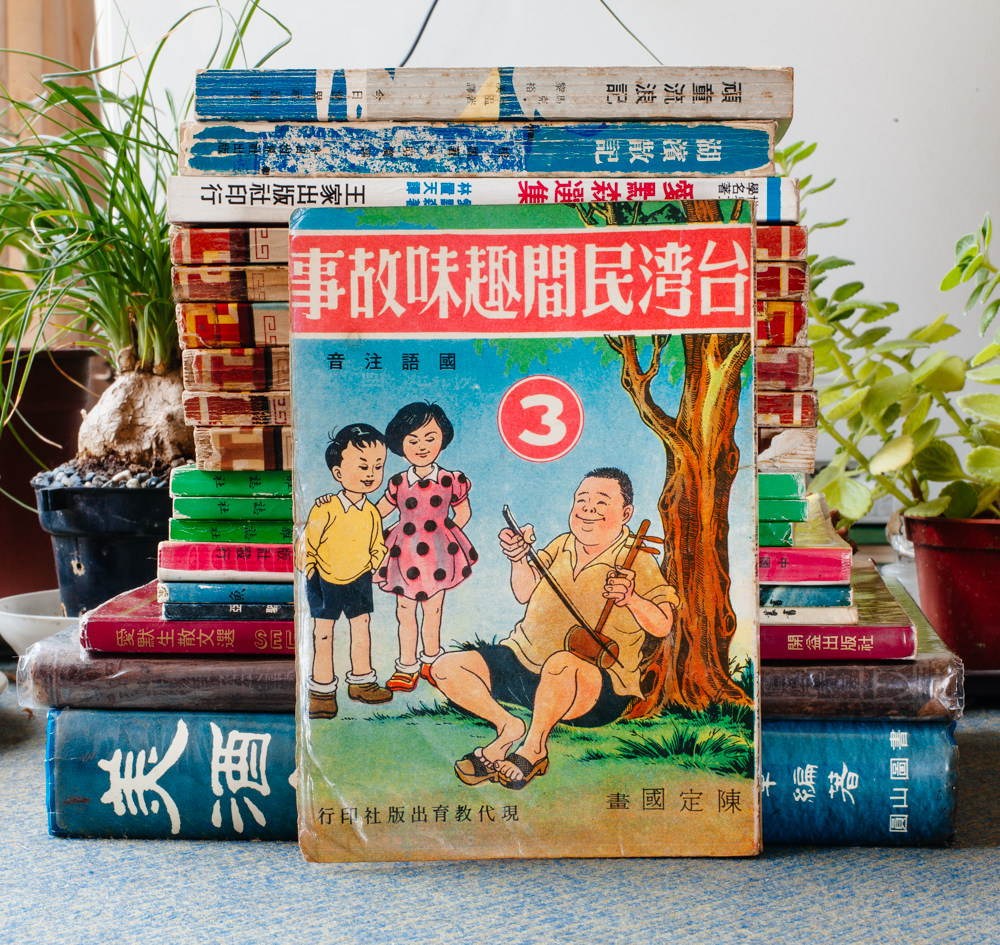

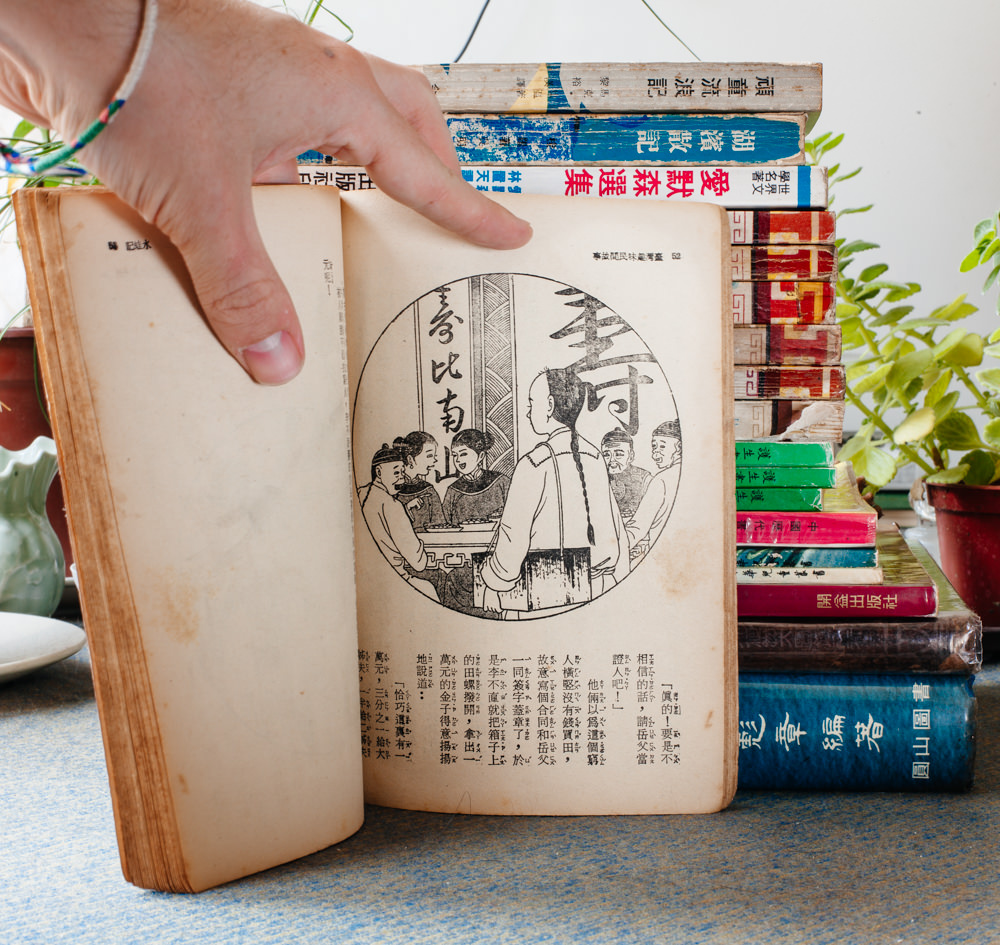

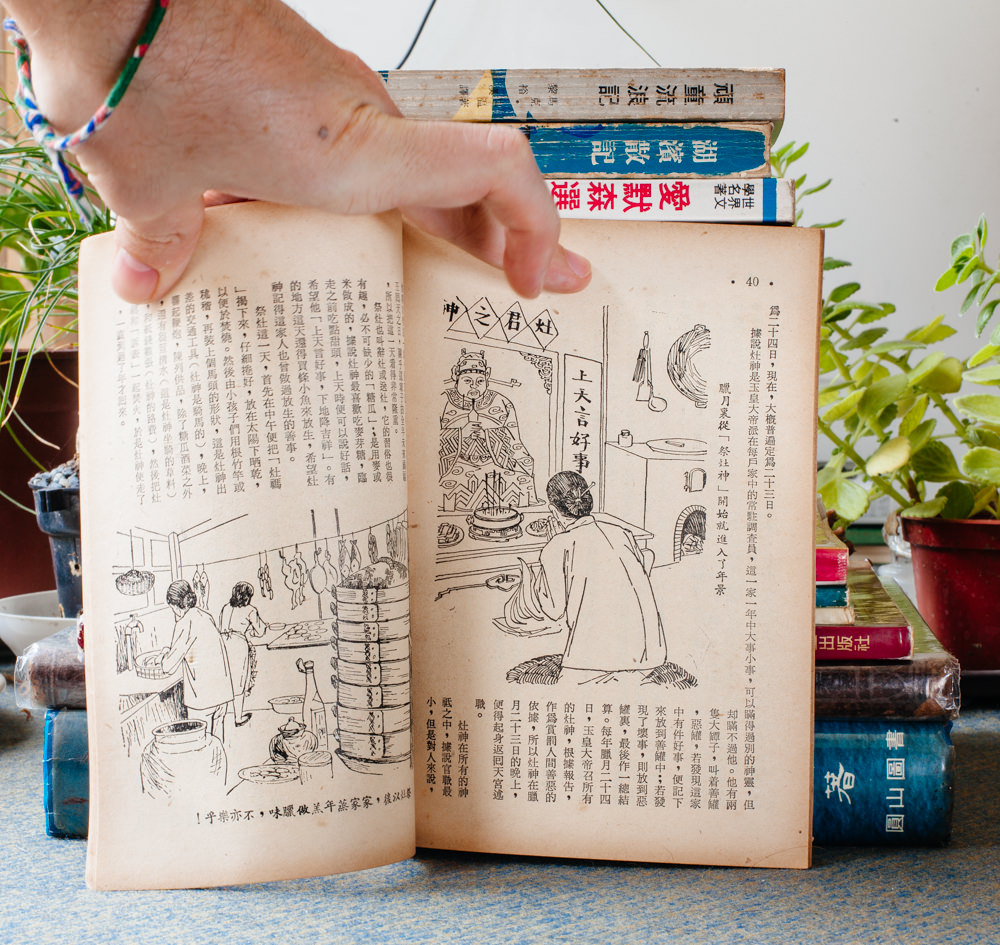

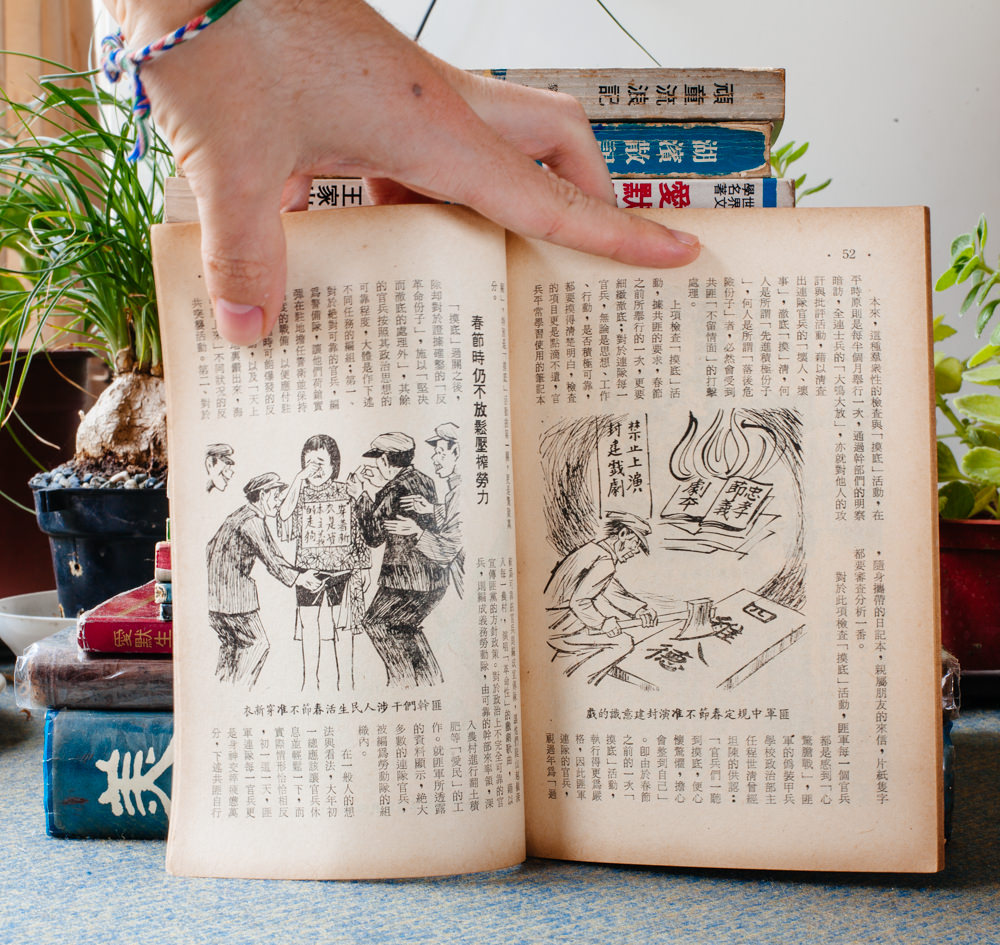

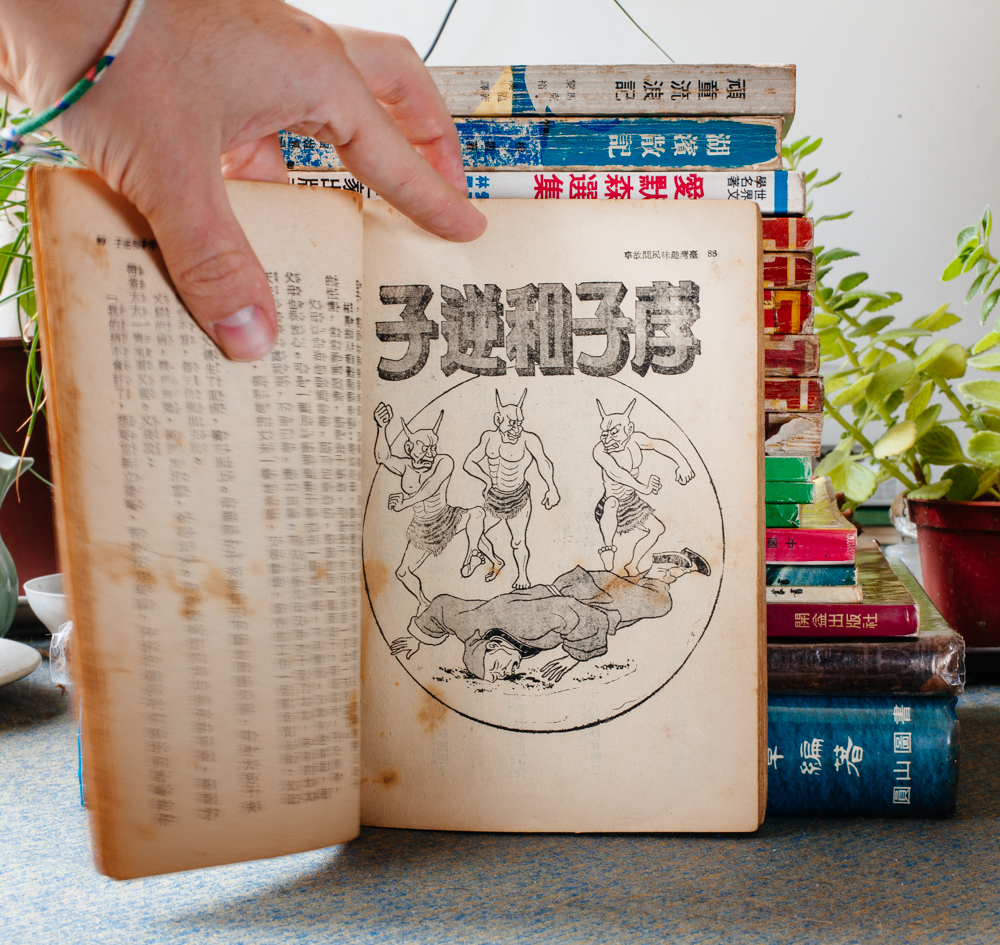

Delightful Folk Stories of Taiwan

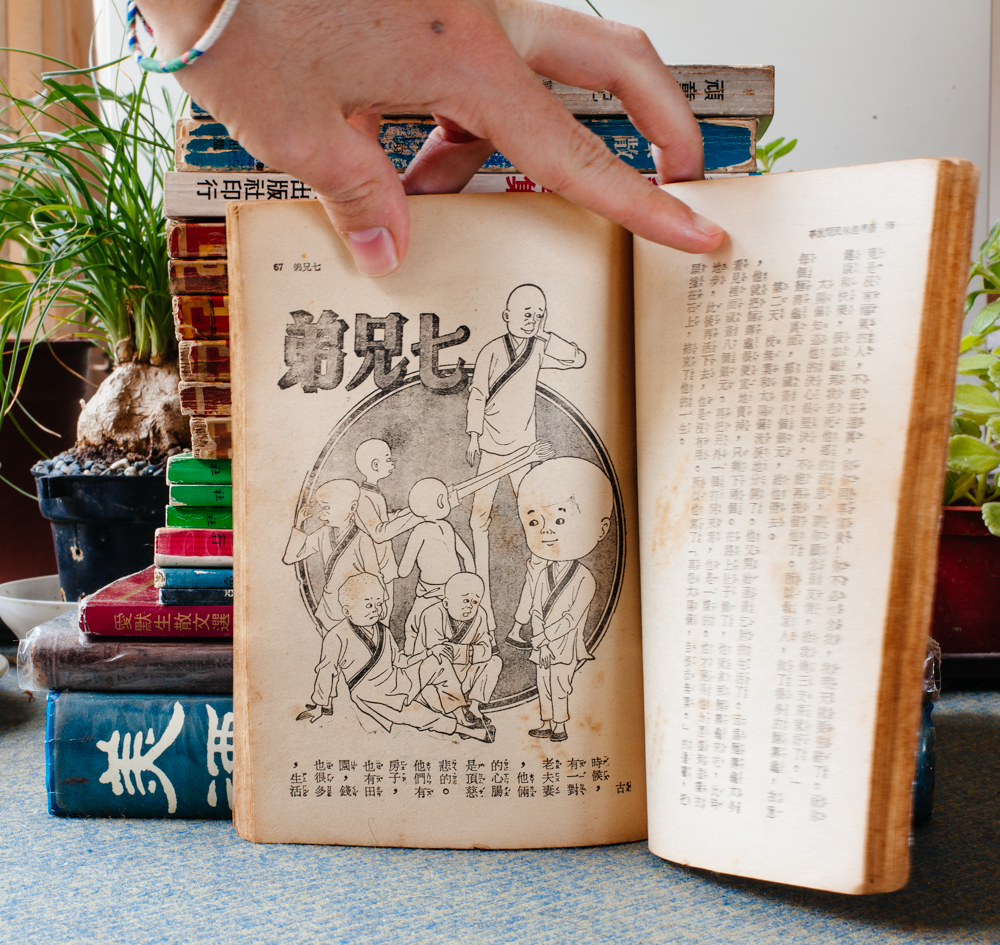

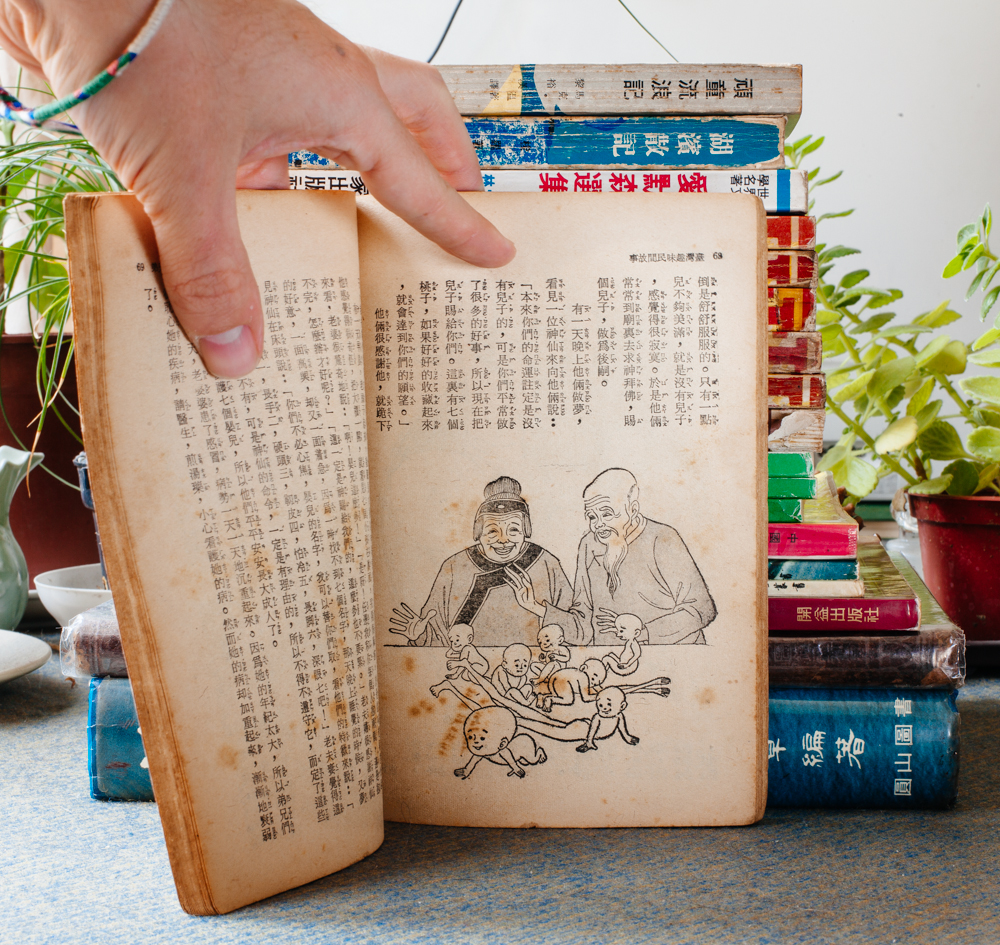

Excerpts from various children’s books

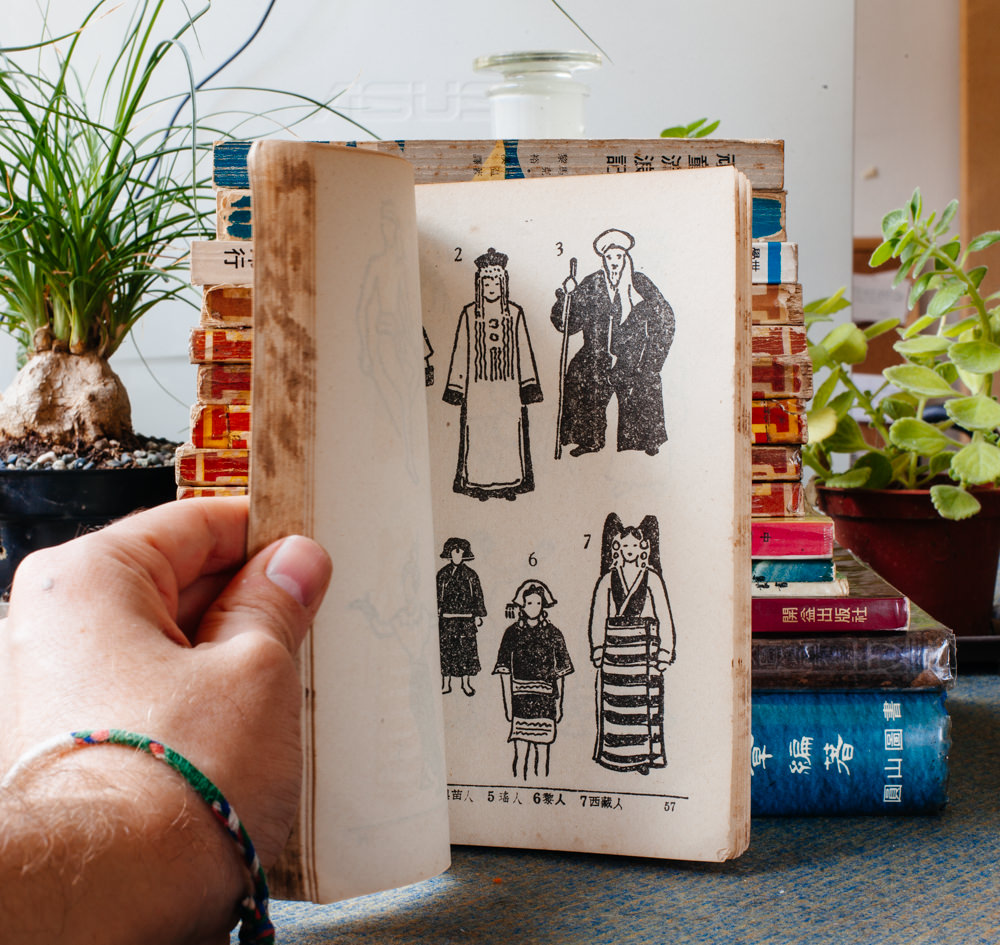

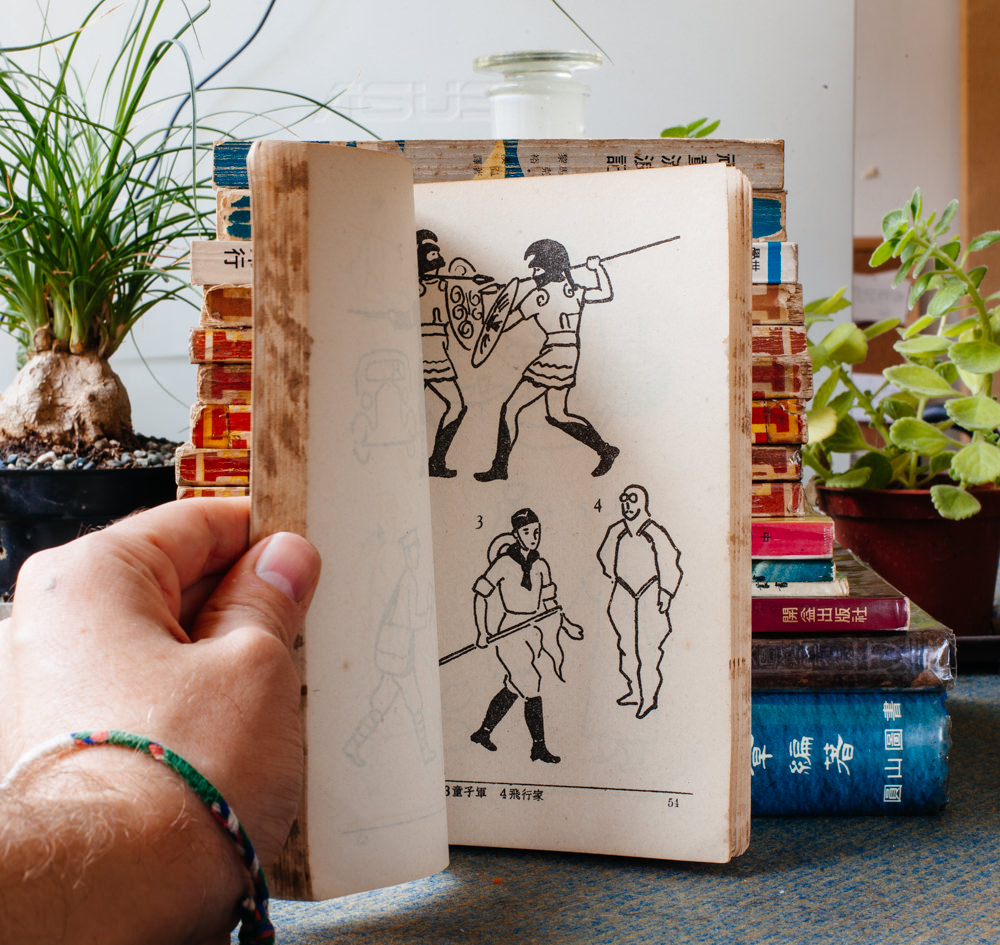

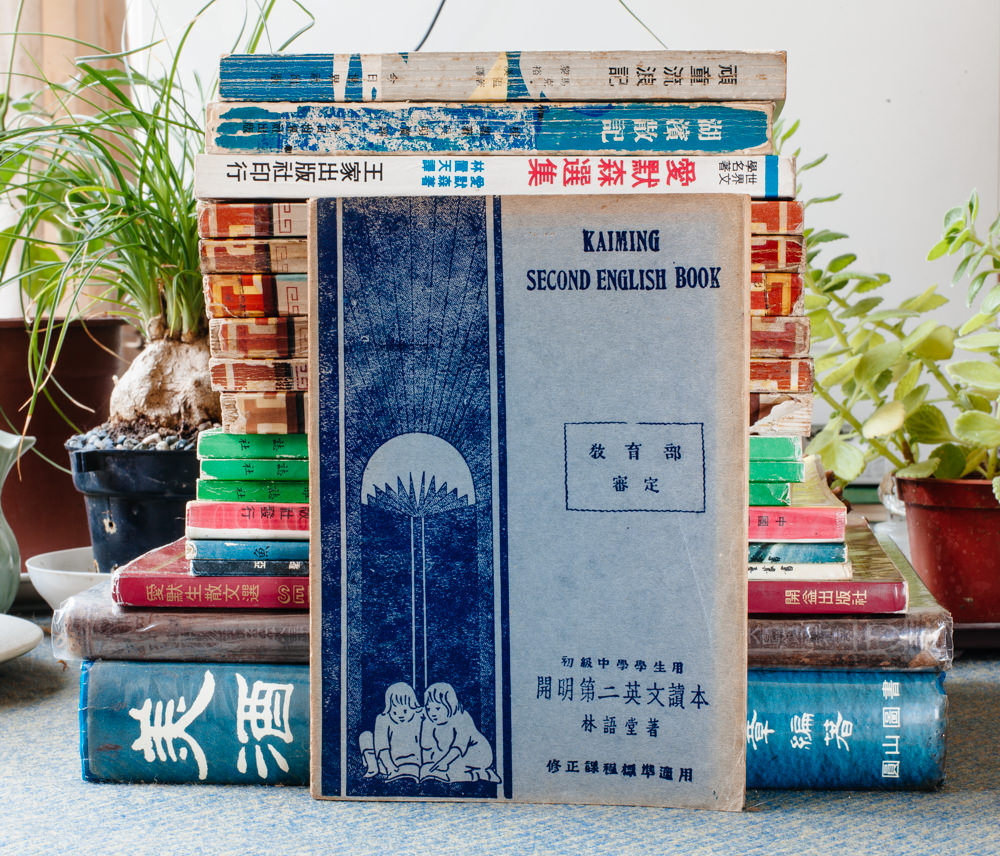

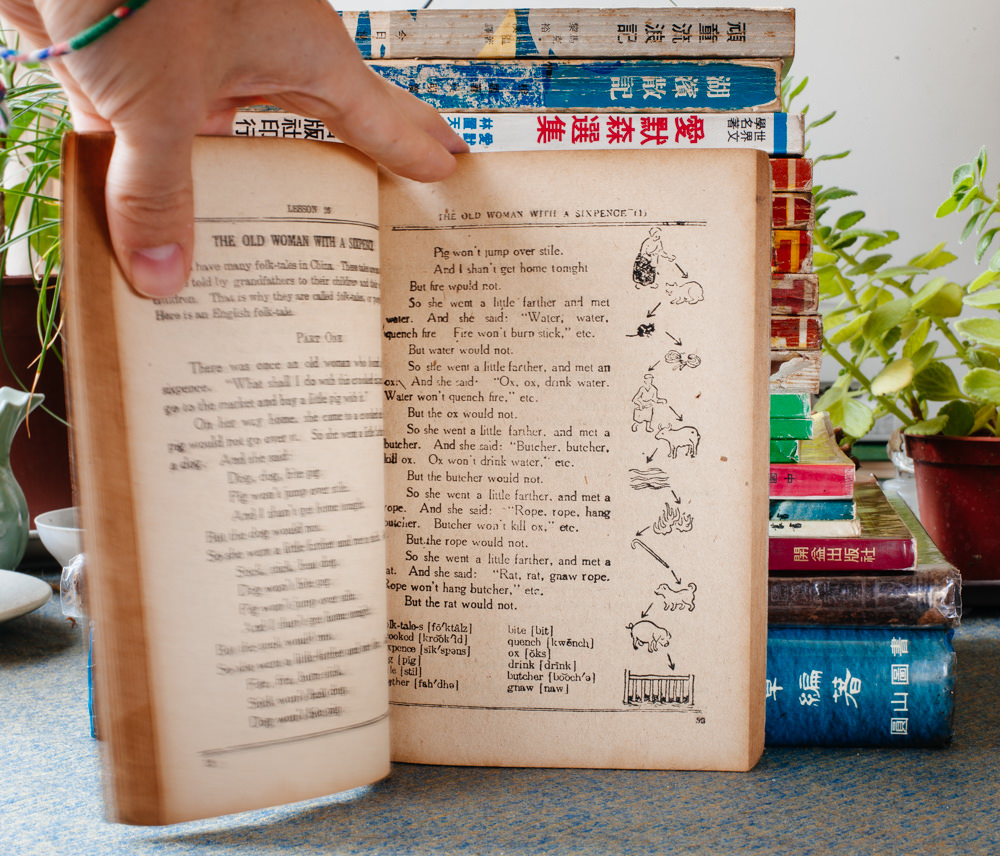

Kaiming Second English Book (This primer was written by one of the most important literary figures in the Chinese speaking world at the time, the Harvard graduate Lin Yutang. Curiously, it was also illustrated by Feng Zikai, who has another selection above)

- Ji RueiTong

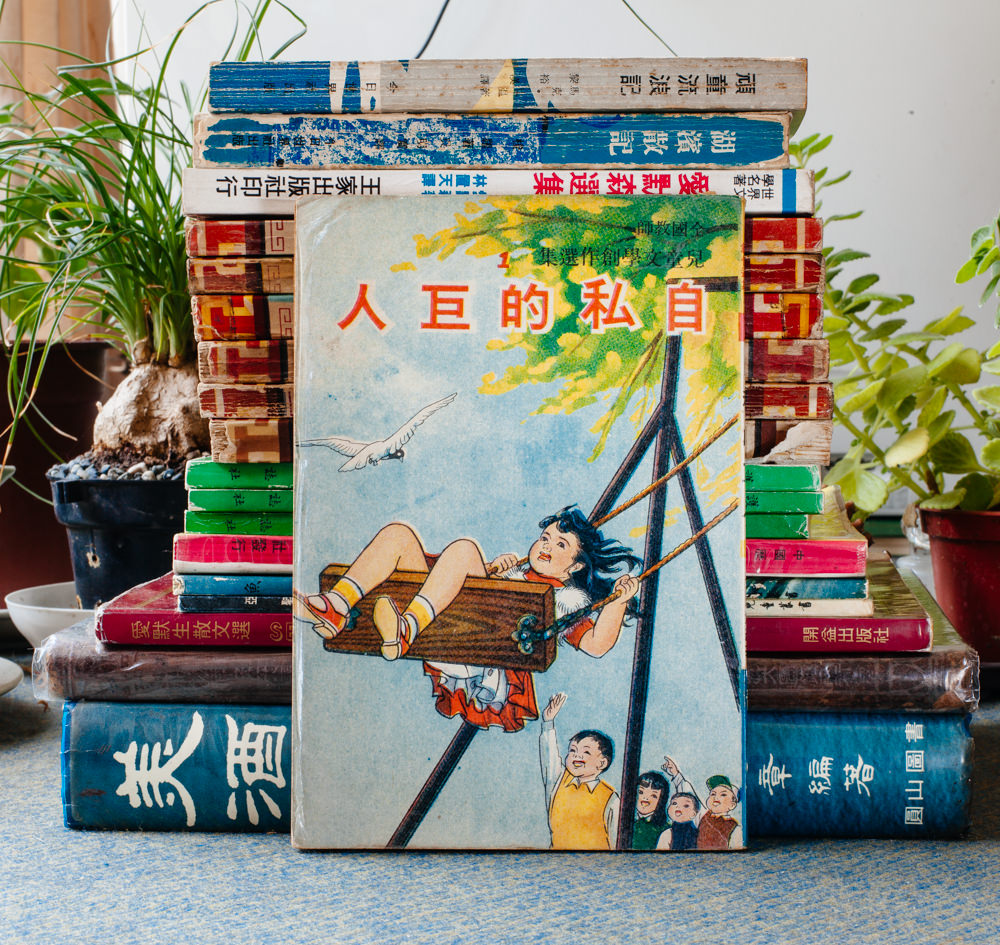

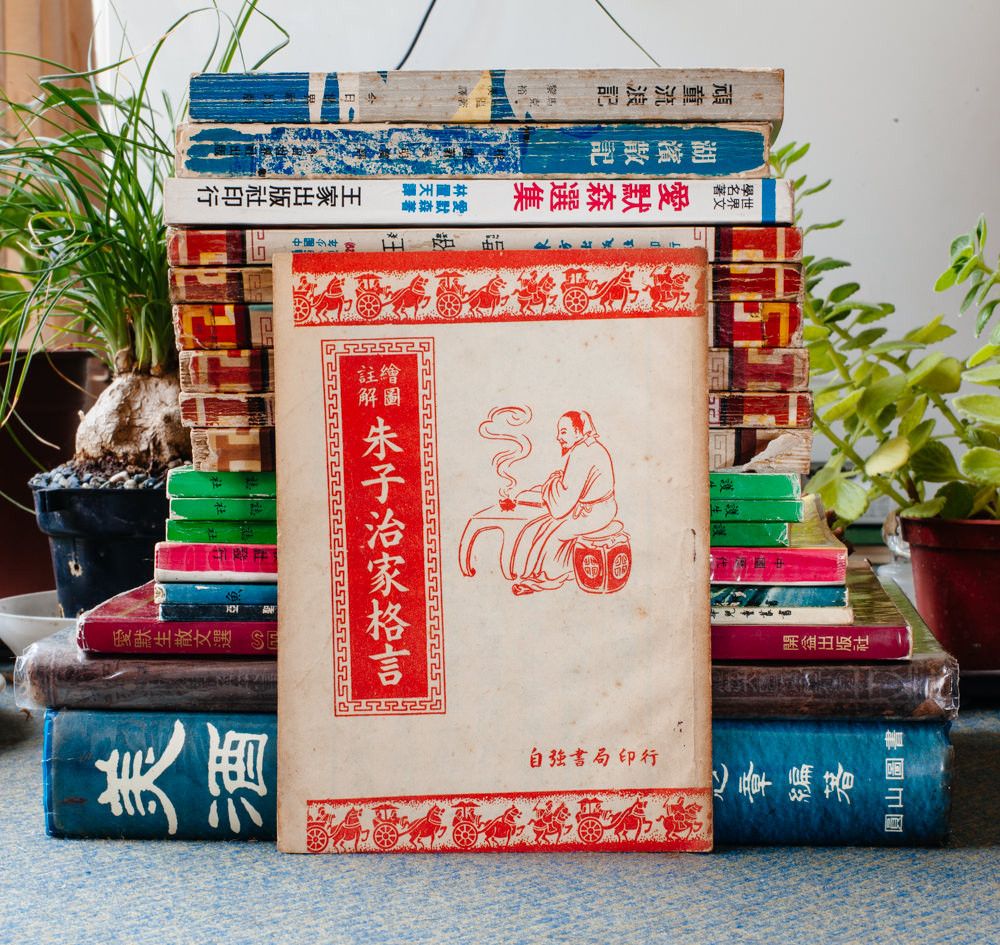

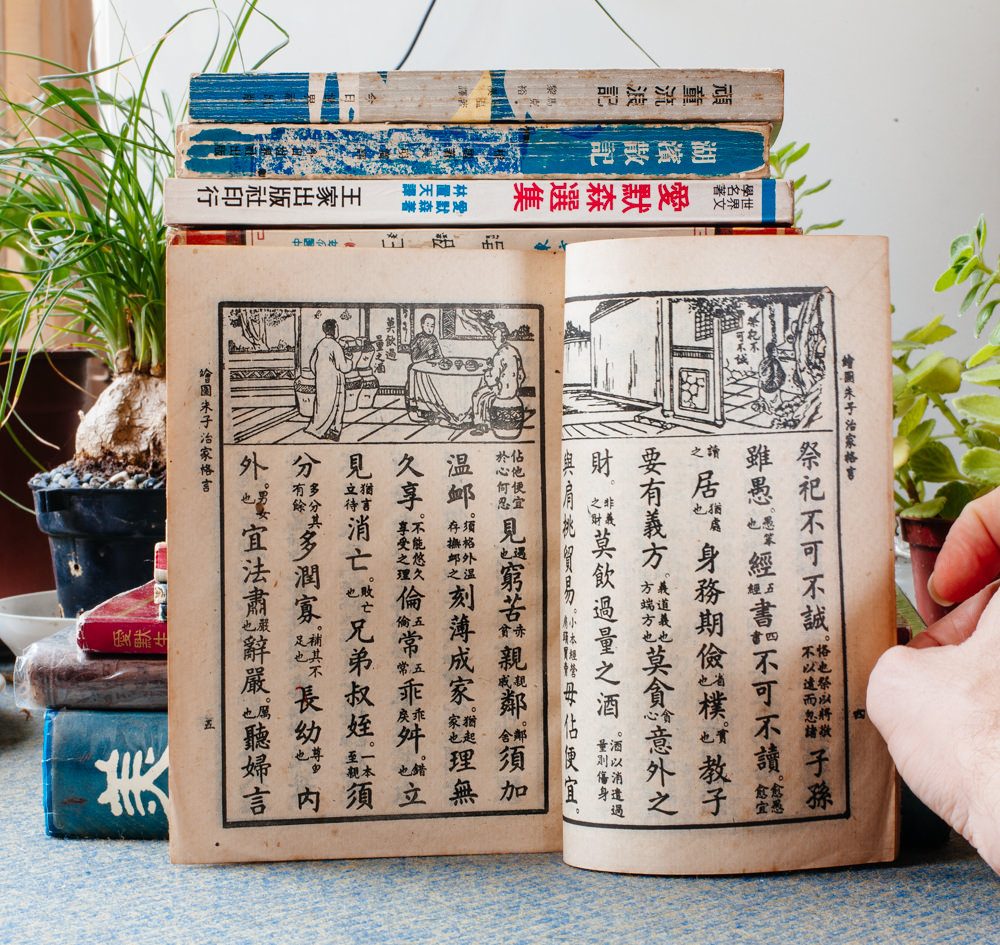

For the Kids

The Case of Shi Gong

The Selfish Giant

Master Zhu’s Family Doctrines

- Three Character Classic (Most likely written in the 13th century, this is one of the most important educational texts in Chinese, widely used in Taiwan up till the 1960's. It's an amazing feat of writing, each line consisting of only three characters and using a wide variety of characters and grammatical patterns to make it a useful tool for children learning the written and spoken language. In addition to its use in language education, the text also neatly sums up the entire world-view of Chinese Confucian thought, helping to indoctrinate numerous generations of Chinese children. The very famous opening lines illustrate a line of thought seen as elemental to later Confucian orthodoxy, as explicitly stated by Mencius. The lines are:

人之初 (rén zhī chū) People at birth,

性本善 (xìng běn shàn) Are naturally good (kind-hearted).

性相近 (xìng xiāng jìn) Their natures are similar,

習相遠 (xí xiāng yuǎn) (But) their habits make them different (from each other).

[g] Keroncong, with special guest

The above is one of my favorite professional recordings of the Indonesian music known as Kroncong (also: Krontjong, Keroncong. For a truly worthwhile read, please follow this pdf link and read about the music's long and diverse history, a fascinating angle that I don't much address in this entry). It was also one of the first songs that exposed me to this music that has always felt both similar and foreign. While I now have other relations to the music, at first, it was simply Kroncong’s melodies and rhythms - its musical style - that drew me in.

I had long been familiar with Gamelan ("traditional" Indonesian ensemble music), and when I first heard the music known as Kroncong, I felt some of their pleasing similarities. While one style seemed to more closely resemble the saccharine and familiar melodies of western popular music (see 'Bengawan Solo' below, the most famous of all Kroncong songs), the audible likeness to Gamelan music seemed more pronounced in the Kroncong style known as Langgam or Langgam Jawa. In this form, the bass and kroncong (an instrument similar to the ukulele) seemed to mimic, in a more portable way, the sounds and rhythms of the massive gongs and percussion instruments in the huge Gamelan ensembles. Check 'Putri Gunung' above and 'Wuyung' below to listen to a few Langgam favorites from Andjar Any, Toeti HP and their Orkes Kroncong Bintang Nusantara.

While many hundreds of variations exist of 'Bengawan Solo,' a song originally written by Gesang, there was something about this recording and the singer's glances and voice that made this version stand out. The video also includes a variation of 'Jali Jali'. Below is another favorite, 'Wuyung.'

Both forms of Kroncong (there are others, as well) could indicate “somewhere else; somewhere new,” in a geographical way, but the “somewhere else” was, for me, almost entirely musical. The krongcong's use as a percussion instrument, the female singer’s emotional and fluid voice, the freely improvisational introductions of the violinist, the ample use of rubato - their forms felt different and hit me directly.

An old and rather beautiful shot of one variation of instrument combinations for a Kroncong band. For another well-researched essay on the history of Kroncong, please click here. While it can be difficult to follow, it's also oftentimes fascinating.

Some music challenges us and multiplies the wrinkles in our brain, changing the way we hear and listen. Other music has a certain, mostly undefinable, power to resonate with our heart's own strings. Kroncong did and does both to me. The style has not loosened its affect on me, an influence that I trust is as deep in its impression as it is colorful.

Admittedly, the music also has a referential power, as it brings me back to the time I spent in Java, Indonesia, when I first met Timbil. As it would turn out, he would bring me even closer to the music. So let me, in an abbreviated fashion, extend that privilege to you.

I met Timbil Budiarto in Indonesia in 2014. Gintani Swastika, a curator and member of the Ace House Collective, introduced me to him at LifePatch, both of these organizations important and unique cooperative groups in Jogja, located centrally in the island of Java. At the time, we had an amiable conversation, enough to remember his face. Then, about two months ago, at an art performance in the hills of south Taipei, I was pleasantly shocked when I randomly recognized his face in a crowd. We reconnected for a bit and, over the remaining month that he was in Taipei, had the opportunity to spend time together and have a few substantial conversations.

In one of those conversations, when I mentioned my near-obsession with the Indonesian style of music known as Keroncong, he quickly replied, "My mom's a Keroncong singer." Hearing this, my heart jumped. Even better, he said he had brought recordings of her performing with her friends.

When he saw the extreme excitement on my face, I think he felt it was necessary to add, "She's not a professional singer." Certainly this was no problem, and in some ways it was more encouraging. The non-professional (or, more accurately, when players "play for fun" as opposed to aspiring professionals who have not yet reached the professional stage) seems to be very much in touch with what I think of as music and its foundation: a way to sonically celebrate and enjoy life, and create harmonies with other things and people. The professional and their output is ever-well documented, transmitted and available for purchase. The non-professionals, I fear, dwindle in number. So, too, do their ensembles, sing-alongs, and choirs as more and more of us only consume music, instead of take part in it. The professional trades their time for someone else's money. The non-professional trades their time for time. Certainly there's something to this, and I believe it can be felt when playing "for fun." Although, when Timbil mentioned his disclaimer, my response was an abridged, "not a problem at all, I want to hear the recordings!"

A week or so passed before I invited him over to my home with a number of other friends. After casually drinking, snacking and lounging around, he told me that he had brought his hard drive that included some of his mother, Sumini Soerapto, and her friends' Kroncong performances. Eagerly and without hesitation, I brought Ruei and Timbil into my studio. After copying the folder containing the media onto my computer, I loaded one video.

As we watched the home video, it was hard for me not to get emotional. It was difficult not only because of the intervals, scales and the melodic rhythms of the musical style that, before, had already had an extremely inebriating effect on me; it was also hard because I was considering and feeling the strange intersections of that moment. Watching the same video together at the same time, Ruei, Timbil and I were certainly affected in entirely different ways. Physically and musically together, we were also consciously isolated. Timbil, of course, was affected in a very personal and direct way; as he watched, he pointed out his mother and his father. Also, when certain musicians' faces came into focus, he would softly add, "he's now gone," "so is he," amplifying the enigmatic power of documentation - something gone is still, in a lesser form, here.

It was a privilege to share what seemed so personal. The different sounds and images produced many different intersections in the short time we watched together. There were dissonances and harmonies, the krong krong of the kroncong instrument (this is where Krongcong gets its name from), and leisurely breaks between songs. Sometimes they were performing under a small roof outside during the day, breathing the fresh air as they performed with their feet to the ground, having removed their shoes when they stepped onto their stage. There they laughed together, played, stopped, started and, at times, looked directly into the camera. And we, the viewers, looked back.

***********************************************************************

These videos will have different affects on you as they had on me.

Or Ruei.

Or of course, Timbil

(much less his mother),

but I feel very happy to be able to share this with you and I have to thank Timbil Budiarto and his mother, Sumini Soeprapto, for allowing me to do so.

His mother shared her voice with her fellow musicians;

They recorded it and shared it with her son;

her son shared it with his new friend,

and his new friend now shares it with you.

While the music doesn't start until around 0:40, I highly recommend you watch from the beginning to get a sense of the surroundings. Along with any of these videos, if you'd like to see them larger, just click on the link on the top edge of the video and watch it full-size at youtube.

I took the liberty to post a snippet of the first take of this song. The singer's focus and the movement of her eyes and hands seem to synchronize so comfortably with the music. Her reaction to missing her queue towards the end is fun to see in a "I know exactly how that feels" kind of way. Her recovery into the perfect take 2 is in its complete form below.

This is Timbil's mother, Sumini Soeprapto, and my favorite recording of these performances. Her voice is incredibly affecting for me and the rhythms of her ensemble mates at 2:48 that lead into the changes at 3:50 are so comfortably driving. It's the intervals like those of this song, (as well as 'Putri Gunung,' and 'Wuyung' above) that are the most gripping and moving I've encountered in Kroncong. Watch this video to the end.

Extras,

for those who still want more: